Liberal Constitutionalism and Us

Michael Greve’s April 2012 post “Constitutionalism, Hegel, and Us” had several significant points in his short essay masquerading as a blog post. Greve notes that liberal constitutionalism per Hegel’s argument in Philosophy of Right has a problem, a big one.

[P]olitical liberalism (Hobbes, Locke, Kant, and, with some qualifications, Rousseau) confuses civil society with the State. Again, that makes us nervous; but the distinction has a very large kernel of good sense. The principle of liberal constitutionalism, Hegel says, is “endless subjectivity,” or what we call “individualism.” A liberal constitution is a contract among individuals, who consent to limits on their autonomy insofar, and only insofar, as they are consistent with individualist principles. (Think Locke’s Second Treatise.) To state Hegel’s central objection at phenomenological level: you can’t run a free country on that basis.

So we need more than individuals. We need a society of persons constituted by familial, local, religious, and political attachments, recognizing that personhood contains aspirations and purposes that place it beyond the scope of state power. Society “possesses primacy over the state.” The state must serve the ends of the human person. On this basis we can relativize the state’s value. It has a “service-character” because its ends are not coextensive with the ends of human society and are restricted to certain enumerated purposes.”

But we have new problems, don’t we? If the basic aspects of human life, natural and supernatural, are displaced by the denizen of late-modernity who is transiently and thinly engaged with others, existing in a post-political, post-familial, flat-souled order, then the problem that emerges in such a thinly conceived understanding of human beings is one of content that fills the private order or the order of culture against the order of the state (or in a post-political dispensation the order of the administrative state). Of significance is that our benevolent bifurcation of society and state is inherited from a foundational common law context of society where the state exists chiefly for the human person, not the person for the state. Does America’s original constitutional division of power, despite its flaws, better accord with the reality of the human person in a way that is more fitting than the current allocation of power and its strange mélange of egalitarian collectivism and autonomism?

Let us get to the good part. Our responsibilities as contemporary citizens of the American constitutional order are both more challenging, but paradoxically clearer given that modern political promises, or modern ideological commitments, are increasingly implausible. In basic terms, the American postwar order has been constructed on the pillars of a metastasizing welfare state and an increasingly lawless administrative state, a secular and highly individualistic order (imposed largely by federal courts), strangely combined with a rather relentless egalitarian and redistributive quest, among other unpleasant realities. These attempts to define our happiness, our equality, our safety, and our mystical, evolving liberties have led, if not to incipient failure, then to confusion and impotence. Part of this impotence is seen in the public fisc, which is beyond mere course correction, and will require a radical reorganization of the incentive structure and distribution of those entitlements that our nation can still afford to provide. Public spending excesses and endless debt prompt immediate fears for America’s future. Advocates of liberty and human dignity, however, must also take the opportunity to apply practical reason to man’s nature and its relationship to the social and political order.

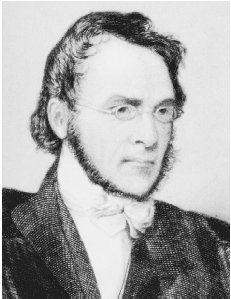

Orestes Brownson, one of America’s most astute constitutional critics and friends, came to the problem of personhood to political liberty from his great concern about the rise of abstract, universal theorizing that appropriates the Christian dogma of human equality, but wrenches it from its theological context. Modern dogmatists turned equality into an ideology, making it into an immanentizing quest of political unity at the expense of the concrete person and the political order that provides for human flourishing. In his fullest statement on American constitutionalism, The American Republic, Brownson urges that the resources within the American constitutional system that restrict the modern political temptation of either hyper-centralization or anarchy are most evident in the institutions and practices of American federalism. But such federalism needed better thinking, Brownson believed.

Federalism must be understood as a mediating principle that situates man between the particularity and universality of political experience by informing him of the limitations and aspirations of man’s political being. To avoid the political pitfalls of a brutish personal democracy or, alternatively, a rationalist universalism, the American system attaches the person to the particular state of his residency. This particular attachment makes sense of our limited, finite nature, and its inbuilt need for local loyalties and devotions. However, the American republic has also made provision for human equality in the Union itself, a Union coterminous with the States, and has therefore a principled way to overcome local tyranny and inequality. “The Union and the States are coeval, born together, and can exist only together. . . . The Union is in each of the States, and each of the States is in the Union.”

For America, constitutional government reaches its apogee in the functional divisions of power that go beyond mere institutions or separation of classes and interests. Brownson opines that the political teleology of America is “to realize that philosophical division of powers of government which distinguish it from both imperial and democratic centralism.” Brownson’s basic formula is that general relations and interests are distinct from particular relations and interests. Thus, state and federal layers of government each have their own province of operations, and hold authority in their separate spheres, while relying on the “interdependent” work of each government, state and federal, for the accomplishment of the full project of constitutional government.

The States are sovereign only in their unity. Citing John Quincy Adams, Brownson argues

the States hold from the Union, not the Union from the States. The States without the Union cease to exist as political communities: the Union without the States ceases to be a Union, and becomes a vast centralized and consolidated state, ready to lapse from a civilized into a barbaric, from a republican to a despotic nation.

Brownson’s larger point is that political modernity is characterized by the need for an abstract unity “democratic centralism” over and against legitimate countervailing authorities in the government and social order. Such unity is based on an ideological insistence for equality, sameness, the reduction of human particularity to a common denominator. A counter tendency in political modernity is individualism with each element constantly fighting other elements for control. It is the American Republic that is built on “catholic principles.” Beyond antagonism, the American system, has the possibility given “its division of the powers of government, between a General government and particular State governments,” to realize a dialectical whole of liberty and authority, the individual and the state.

The problems of our constitutional order remain what Brownson identified in 1865, which emerge from the rejection of liberty as an inheritance, and a blessing, to note the Constitution’s Preamble, in favor of an egalitarian telocratic future which eliminates the balance of federalism and union. Local decision-making becomes suspect to the extent it dissents from the forward march of sameness that collapses the different aspects of personhood into a thin individualism. Freedom exercised by communities within a nation becomes an easily dispensed good in favor of justice defined as equality.

If liberty is a blessing, its possession and exercise must be intrinsically beneficial to the person as a citizen. But the liberty of a citizen, if it is to be a blessing, must also require some account of its profitable use, that is to say, liberty must in some way be connected with the good, with self-limitation and justice, and that presupposes a consensus that “We the People” agree to beforehand. This means that America must be reaffirmed as a democratic republic anchored by self-government to meet the five-fold ends of political life: freedom, justice, general welfare, civil unity, and security, as stated by the Constitution’s Preamble, in order that the “blessings of liberty” might be secured. To quote Willmoore Kendall, the task of those who wish to preserve and vindicate our constitutional order against its antagonists is to show that in the American republic the constitutional consensus that rules our democratic forms and our liberty differs mightily from the unbounded democratic temptation of progressives.

[T]he issue is not whether the American system is or is not “democratic,” but which of two competing definitions of “democracy” –that which equates it with government by the “deliberate sense” of the people, acting through their elected representatives, and that which equates it with direct majority rule and equality–should prevail, and, in doing so, learn to expose the falseness of the Liberal’s claim that the reforms he proposes can properly be defended in the name of democracy.

This outline of the substance of our contemporary problems also underscores the American Constitution’s rejection of a monistic political order that collapses the loyalties of persons into a spoke and hub organization of state and citizens. The need is to provide a theoretical defense of the American practice of liberty achieved through the separation of the order of culture and the order of the state as a temporal fulfillment of the dignity of the human person. This must be the first order of a competent American conservatism.