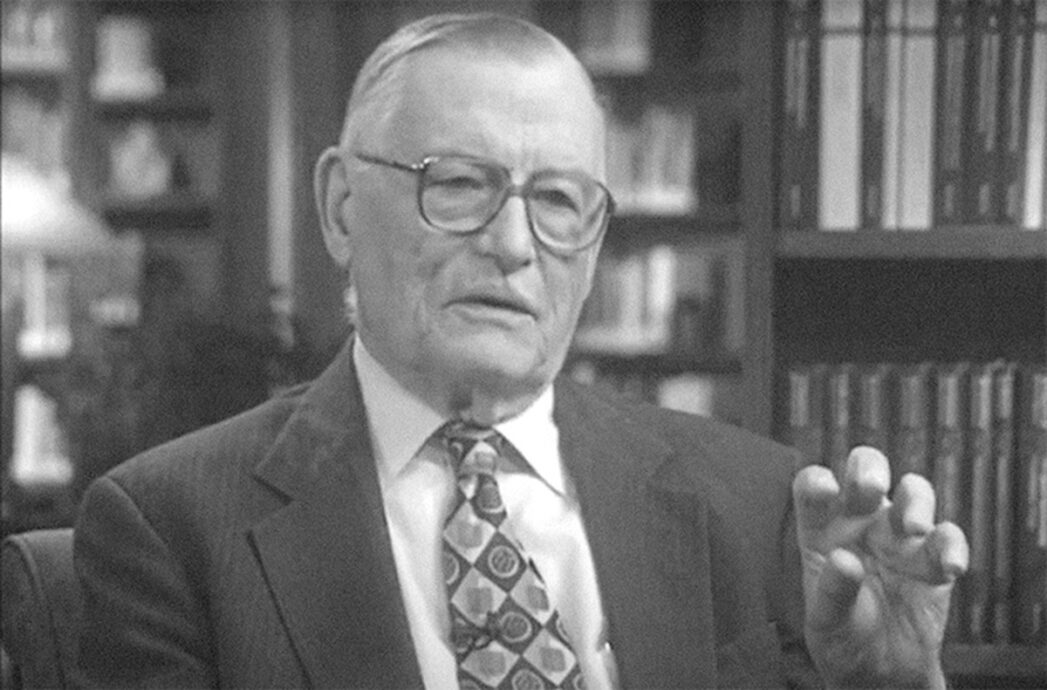

James Buchanan’s Final Thoughts on Freedom and Law

One of the most remarkable characteristics of our friend and mentor, James Buchanan, who passed away on January 9 this winter, was his ability to rethink a question from the foundations unencumbered by what he had written on the topic before. We were fortunate to witness Buchanan’s multiyear rethinking of the foundational question of whether a market economy is stable. (The lectures were recorded and posted on YouTube: 2010, 2011, 2012. The papers themselves can be found on the Jepson School web site: 2010 (link no longer available), 2011 (link no longer available), 2012 (link no longer available).)

The project began after the economic crisis with the question of why Chicago-influenced economists got things so badly wrong. Near the end of the first of three tightly linked papers, Buchanan digresses to note:

The basic Samuelsonian taxonomy was extended to laws and institutions by me and others, but we did not follow through and examine the implications.

Buchanan is referring to a brief paper of 1954 by Paul Samuelson in which the polar cases on public and private goods were laid out, a paper that influenced Buchanan’s entire career. Although Buchanan’s club theory famously pointed to an intermediate case between the purely public and purely private (Buchanan 1965), that contribution did not figure at all in the rethinking.

Instead Buchanan’s rethinking commenced with a restatement of Samuelson’s cases in terms of “partitionable” goods. A private good, such as an apple, is partitionable so if you can consume the apple, someone else cannot. A public good, such as a law, is not partitionable. Indeed, the law “works” in Buchanan’s account precisely because if you are subject to the law, so, too, are others.

Buchanan’s larger point is breathtakingly simple. The mechanism put forward by the generation of Chicago economists who taught him and to which he himself subscribed brings about efficiency within a system of law but it cannot be counted upon to bring about efficiency of the system of law. The result turns upon differential arbitrage possibilities for partitionable vs. non-partitionable goods. Arbitrage over partitionable goods is efficiency- inducing in a way that fails for non-partionable goods. The argument attains very sharp focus in the second lecture:

Economists, generally, have failed to distinguish between exchange interactions that take place within institutional constraints, or rules, and the origins and generation of such rules. I suggested, further, that there is no legitimacy in any claim that “the market” can generate its own rules, at least to the extent that emergent rules meet efficiency criteria.

Rules will be created, of course, but Buchanan’s point is that there is no reason to believe the rules will be efficient.

Economists should never have expected that the rules, conventions, practices, and institutions generally that emerged in the quasi-anarchy of the financial sector would meet efficiency norms. So long as we acknowledge that some sets of rules or constraints are better than others, we are, nonetheless, invoking an evaluative standard of some sort. It is necessary, however, to go beyond the Samuelson taxonomy and to treat, specifically, the publicness characteristics of rules.

If rules are created via markets then we have an extra layer of complication because we cannot count on the pecuniary motivation of the legal entrepreneurs vanishing in the same way that the motivation of entrepreneurs inside a legal system vanish:

To the extent that goods which serve as substitutes for genuinely nonpartitionable goods are produced in markets, their production must be motivated by profit or rent-seeking entrepreneurs, whose strictly pecuniary objectives may be differently directed from any stylized ideal provision under some benevolent and omniscient collectivity. Indeed, in extreme cases, the market response to the demand for the basic services involved here may be welfare reducing rather than welfare enhancing. We think of Viner’s early treatment of customs unions (Viner, 1950).

This argument connects with Buchanan’s Rawlsian position that the selection of rules requires different considerations than actions within the rules.

In their book The Calculus of Consent, Buchanan and Tullock (1962) suggest that agreement on rules becomes relatively easier to achieve than agreement on specific allocation-distribution alternatives within existing rules because the sequential extension of rules necessarily places the individual participant behind a “veil of uncertainty,” akin to the normatively grounded position behind a “veil of ignorance,” made familiar by Rawls (1971).

In the Summer Institute lectures, Buchanan raised familiar themes, e.g., his unhappiness with evolutionary arguments that purport to find efficient equilibrium (Peart and Levy 2008) and his even deeper unhappiness with the removal from the economist’s tool kit of anything that would plausibly speak to reforming the system. Here, as Buchanan 2008 suggests, perhaps we need to learn from Adam Smith. What is it that allows us to step behind Rawls’ veil of ignorance at the constitutional moment? In Smith’s account an alternative to disinterestedness comes from our fascination with and preferences for systems of the mind (Levy and Peart 2013). In our very last conversation with Jim, we talked about how Smith’s “love of system” might be a way to revive a view of governance common to his great teacher, Frank Knight (1935) and Rawls. One of the larger themes in Buchanan’s work is the importance of motivational homogeneity; the supposition that political actors are characterized by the same motives as private actors. As economists have always had an interest in reform perhaps all that needs to be done is to extend motivational homogeneity to the agents we study, to say that we and those we study share motivational structure and interests.

What might stop the exploitation by legal and political entrepreneurs who will cause the constitution to drift from its beginnings? This problem, of the instability of rules, formed a major topic in the long correspondence between Buchanan and Rawls (Buchanan and Rawls 2008). The title of one of Buchanan’s last books, coauthored with Roger Congleton, Politics by Principle, not Interest (Buchanan and Congleton 1999) describes the enterprise. If we agree on principles, whether they be Smith’s system of natural liberty or Rawls’s justice as fairness, we have a way to judge whether political-legal entrepreneurs are moving us away from the foundations to which we have consented.

References

Buchanan, James M. 1965. “An Economic Theory of Clubs.” Economica 32:1-14.

Buchanan, James M. 2008. “Let Us Understand Adam Smith.” Journal of the History of Economic Thought 30: 21-28.

Buchanan, James M. and Roger D. Congleton, 1999 Politics by Principle, Not Interest: Towards a Nondiscriminatory Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, James M. and Gordon Tullock. 1962. The Calculus of Consent: Logical

Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Buchanan, James M. and John Rawls. 2008. “The Buchanan-Rawls Correspondence. In: The Street Porter and the Philosopher: Conversations on Analytical Egalitarianism. Edited by Sandra J. Peart and David M. Levy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 395-415.

Levy, David M. and Sandra J. Peart, 2013. “Adam Smith and the State: Language and Reform.” Oxford Handbook on Adam Smith. Edited by Chrisopher Berry, Craig Smith and Maria Paganelli, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

John Rawls’s Marginal Notes on Frank Knight. [1935] 1951. Ethics of Competition. New York: Augustus Kelly.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press,

Peart, Sandra J. and David M. Levy. 2008. “Discussion, Construction and Evolution: Mill, Buchanan and Hayek on the Constitutional Order.” Constitutional Political Economy 19: 3-18.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1954. “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,” Review of Economics and Statistics 36: 387-89.

Viner, Jacob. 1950. The Customs Union Issue. New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.