The opponents of the Electoral College, in attempting to undermine support for the institution, have painted it with an unfair half-truth.

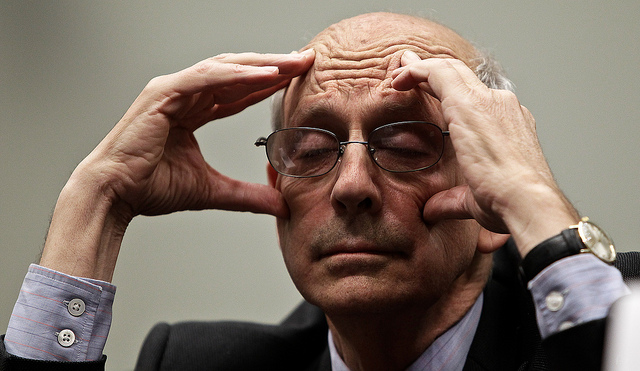

Why Justice Breyer Should Put Down the Baguette and Grab a Hot Dog and Beer

The current issue of the New York Review of Books contains a delightful yet potentially bewildering interview with Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Breyer on the pleasures of reading Proust and other French writers in their original language. Long obsessed with all things French, Breyer has consistently endorsed the incorporation of European jurisprudential insights into American constitutional decision-making in an attempt to refute originalist interpretations of the American legal and political tradition. Judge Richard A. Posner, in a now-famous critique of Breyer, correctly suggests that what is ultimately at stake is a disavowal of the “liberty of the ancients” for a new and “active” liberty and theory of unrestrained democracy embodied in recent studies of European law and political thought.[1]

According to this view, social and political life is primarily concerned with the acquisition of wealth and power, which other liberal thinkers describe as “possessive individualism.” This philosophical approach assumes that the desire for personal aggrandizement is primary among humankind’s longings. With antecedents in the thought of Rousseau and Kant, “interest”–and democratic life–is viewed by Breyer and his guides as synonymous with human self-determination or the search for autonomy. James Madison and John C. Calhoun rejected this narrow view of interest and defended it as an intrinsic manifestation of the body politic, grounded in the community. The natural and evolutionary predilections of the regime ascertained through the most reliable units, the states, deserved protection from the arbitrary exertion of force by the general government against these elements. Viewing the diversity within the community as important to the survival of the country and as the only practical basis for embodying a totality of concerns, Calhoun mirrored Madison’s earlier plea for “[t]he regulation of these various and interfering interests” as a primary requirement for American politics.[2] But interest, Calhoun declared, should not be defined as purely individual assertion:

It results, from what has been said, that there are two different modes in which the sense of the community may be taken: one, simply, by the right of suffrage, unaided; the other, by the right through a proper organism. Each collects the sense of the majority. But one regards numbers only and considers the whole community as a unit having but one common interest throughout, and collects the sense of the greater number of the whole as that of the community. The other, on the contrary, regards interests as well as numbers–considering the community as made up of different and conflicting interests, as far as the action of the government is concerned–and takes the sense of each throughout its majority or appropriate organ, and the united sense of all as the sense of the entire community. The former of these I shall call the numerical or absolute majority, and the latter, the concurrent or constitutional majority.[3]

In upholding such an understanding of interest, Calhoun more closely resembled Madison than contemporary theories of “interest group” or pluralistic democracy.[4] Madison and Calhoun incorporated similar conceptions of human agency into their appreciation for the decision-making of autonomous or semi-autonomous communities, as well as for the interconnected roles these communities play in addressing the most profound social and political issues that a republic must confront. Instead of relying upon purely private economic and political preferences to synthesize community and regime responses into a composite whole, Madison and Calhoun insisted upon assimilating the deeper, more comprehensive needs of the whole by focusing upon the responses of the communities and the republic in their particularity.[5] A consensus might be possible if the distinct preferences of all communities in a regime were considered, but only after much trial and error. An unrefined or less articulate majority serves only to discourage participation, and ultimately it undermines the regime’s legitimacy.[6]

[1] http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/nov/07/reading-proust/?utm_medium=email&. See Richard A. Posner’s “Justice Breyer Throws Down the Gauntlet,” Yale Law Review, Volume 115, Number 7 (May 2006), p. 1700, offers more detailed analysis of the problem.

[2] Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist, eds. George W. Carey and James McClellan (Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt, 1990), No. 10 (Madison), p. 45.

[3] John C. Calhoun, A Disquisition on Government, ed. H. Lee Cheek, Jr. (South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press), p. 21.

[4] As a commentary on his earlier “Fort Hill Address” (1831) and a reminder of his consistency in this regard, Calhoun composed a public letter to South Carolina Governor Hamilton further clarifying his understanding of interests nearly two decades before writing the Disquisition: “When, then, it is said, that a majority has the right to govern, there are two modes of estimating the majority, to either of which, the expression is applicable. The one, in which the whole community is regarded in the aggregate, and the majority is estimated, in reference to the whole mass. This may be called the majority of the whole, or the absolute majority. The other, in which it is regarded, in reference to its different political interests, (author’s underlining) whether composed of different classes, of different communities, formed in one general confederated community, and in which the majority is estimated, not in reference to the whole, but to each class or community of which it is composed, the assent of each, taken separately, and the concurrence of all constituting the majority. A majority thus estimated may be called the concurring majority” (“To James Hamilton, Jr.,” August 28, 1832, in Papers, Vol. XI, p. 640).

[5] Whereas previous misconceptions regarding the role of interest in The Federalist have been challenged by recent scholarship, Calhoun’s use of the concept has not experienced such a needed re-evaluation. See George Carey, The Federalist: Design for a Constitutional Republic (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989); and David F. Epstein, The Political Theory of The Federalist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

[6] While a political order based upon unanimity is appealing, Calhoun rejected such a possibility because it would prove “impracticable” (Disquisition, Ibid., p. 22).