The Sacred Sounds of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

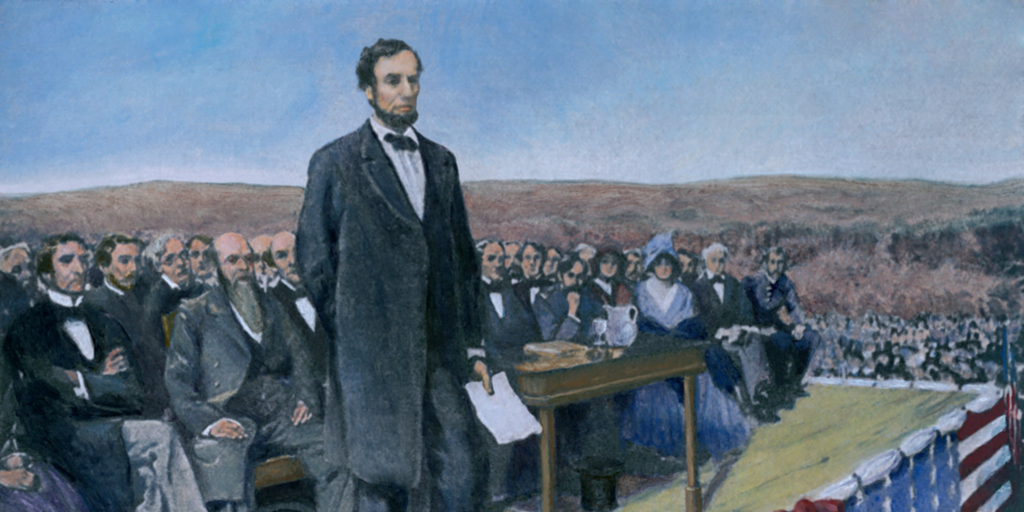

On the afternoon of November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered a brief address at the dedication of a national cemetery on Gettysburg’s battlefield. The solemn ceremony took place four and a half months after Union forces turned back the army of the Confederate States on July 1-3 in the bloodiest engagement of the Civil War. The battle claimed the lives of nearly eight thousand soldiers. Lincoln’s carefully crafted address was barely 272 words in length and required approximately two minutes to deliver. It is widely acclaimed as one of the most poignant and eloquent speeches in American letters.

The Gettysburg Address reverberates with biblical rhythms, phrases, and themes. Its author was well acquainted with the English Bible – specifically the King James Bible. Those who knew him best reported that Lincoln had an intimate and thorough knowledge of the sacred text and was known to commit lengthy passages to memory. His biographer and friend of a quarter century, Isaac N. Arnold, recalled that Lincoln “knew the Bible by heart. There was not a clergyman to be found so familiar with it as he.”

American politicians and polemicists have long employed biblical language in their public discourse because, as an authoritative and sacred text, its mere invocation, it is believed, lends rhetorical weight to their words. The evocative use of biblical language, Joseph R. Fornieri observed, stirs an audience’s “religious imagination.” Such uses of Scripture, which sometimes mimic pulpit oratory, are calculated to persuade by capturing an audience’s attention (with, perhaps, the fear of God), arousing a righteous passion, solemnifying a discourse, projecting an aura of transcendence and truth, emphasizing the gravity of an idea or argument, and/or underscoring an argument’s moral implications or sacred connotations.

Although less obvious, but perhaps as significant, is the use of bible-like language; that is, phrases, figures of speech, or rhythms that resemble, imitate, or evoke the language of a familiar Bible translation. In the American experience, the translation most frequently imitated because of its wide availability and influence is the King James Bible. A mere resemblance to its mellifluous language and intonations infuses rhetoric with solemnity, sanctity, and authority.

No political figure in American history was more fluent in biblical language or adept in appropriating the distinct cadences and vernacular of the King James Bible than Abraham Lincoln. He routinely incorporated into his political prose direct quotations from and allusions to the Bible, as well as a diction resembling the distinctive language of the Jacobean Bible. He often appropriated the Bible and bible-like rhetoric to give authority, moral gravity, and solemnity to his political statements. The Gettysburg Address, perhaps better than any other example of political rhetoric, illustrates how a gifted communicator borrowed language merely resembling the King James Bible to great rhetorical effect. The address contains no direct biblical quotations; however, there are few clauses that do not echo the cadences, phrases, and themes of the King James Bible.

The address begins: “Four score and seven years ago.” Although not an actual biblical quotation, this formulation resembles the psalmist’s familiar calculation, as rendered in the King James Bible, for a man’s “threescore and ten” years of life on earth (Psalm 90:10). From the opening phrase, Lincoln put his audience in a biblical frame of mind.

This clause is prologue for “our fathers,” a phrase evocative of the salutation of “The Lord’s Prayer” (Matthew 6:9-13; Luke 11:2-4), perhaps the most recited prayer in all of Christendom. “Our fathers” is also a phrase with special resonance in the Hebrew tradition in reference to the patriarchs – Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob – the founders of Judaism and the Hebrew nation (see 1 Chronicles 29:18). The word “hallow” a few lines down recalls the phrase “hallowed be thy name” from the prayer Jesus taught his disciples. “[H]allow . . . ground” is also reminiscent of the “holy ground” on which Moses encountered a burning bush (Exodus 3:5; Acts 7:33).

“[O]ur fathers” is followed immediately by the verbal phrase “brought forth.” This recalls the creation story (Genesis 1:12, 21) or Moses’ liberation of the Children of Israel from slavery in Egypt (Exodus 3:12, 32:11; Deuteronomy 9:12, 26) or Mary’s deliverance of the Christ child (Matthew 1:25; Luke 2:7; Revelations 12:5). “Brought forth” calls to mind a theme of liberation, equating the emancipation of African slaves in America with the deliverance of the Children of Israel from Egyptian bondage. This surely resonated with a nation in the midst of a war fought over slavery.

Lincoln’s text is liberally seasoned with other biblical idioms, such as “resting place,” “might live,” “in vain,” and “from the earth.” The concluding line, “shall not perish,” echoes John 3:16, the most cherished and memorized encapsulation of the Gospel in all of Scripture, as well as other biblical passages (Psalm 9:18; Jeremiah 18:18). The phrase “shall not perish from the earth” appears twice in the Hebrew Scriptures absent the negative “not” (Job 18:17; Jeremiah 10:11). Lincoln’s use of this “sternly grand language of the King James Bible,” literary critic Robert Alter remarked, “was a way of giving American English a reach and resonance it would otherwise not have had.”

Lincoln’s choice of the word “struggled” in reference to a battle “in a great civil war” is particularly poignant. “Struggled” appears only once in the King James Bible in the context of another, more intimate civil war that pitted brother against brother – Esau and Jacob, the fathers of two nations, who it is recorded, “struggled together within” Rebekah’s womb (Genesis 25:22). It may seem implausible that Lincoln selected “struggled” with this allusion in mind; it is not out of the question, however, given his fluency with the King James Bible.

The unifying theme of the address, woven throughout from beginning to end, is the conception, birth, death, and new birth of the nation. “[O]ur fathers brought forth . . . a new nation, conceived in Liberty,” Lincoln began. “Conceived” and “brought forth” are the words of both St. Matthew’s and St. Luke’s gospels as translated in the King James Bible to describe a divine child who was “conceived” (Matthew 1:20; and Luke 1:31; see also Isaiah 7:14) and delivered (Matthew 1:25; Luke 2:7) in the flesh (John 1:14). Lincoln thus subtly linked the birth of the United States of America with the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. But that was not all. Like Julia Ward Howe in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” he went on to link the atoning sacrificial shed blood and death of the brave men on Gettysburg’s battlefields with the atoning sacrificial shed blood and death of Jesus Christ on Calvary’s cross, which made possible a new birth and new life for fallen mankind. The soldiers memorialized in Lincoln’s oration, like Jesus Christ, “gave their lives,” in Lincoln’s words, so others “might live.” The nation, Lincoln pointedly observed in the opening clause, was born on July 4, 1776; it was reborn in Gettysburg eighty-seven years later to the day, after having descended into hell for three days of battle, carnage, and death.

Lincoln himself drew attention to the coincidence of the victory at Gettysburg “on the same day and month of the year” the nation was born eighty-seven years before, affirming in the Declaration of Independence the “self-evident truth that ‘all men are created equal.’” Speaking to a crowd assembled outside the White House on the evening of July 7, 1863, having received news of Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln remarked that on the “Fourth of July just passed . . . the cohorts of those who opposed the declaration that all men are created equal [had] ‘turned tail’ and run.” “This,” Lincoln continued, “is a glorious theme, and the occasion for a speech” – a speech he would deliver four and a half months later at Gettysburg.

Through the sacrificial shed blood of this “great civil war,” Lincoln said, “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” A “new birth” evokes the Gospel’s central theme of regeneration and the hope of eternal life through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ (see John 3:3-7). This theme takes on powerful significance in the setting of Lincoln’s oration on a blood-soaked battlefield. In the shed blood and death of the Civil War, the old Union – corrupted by slavery – died, giving hope for a new birth and new life for the Union. Lincoln averred that the nation was born in 1776 committed to, in the words of the Declaration of Independence, the self-evident truth “that all Men are created equal.” This birth, however, was tainted by the besetting sin of slavery. In the abolition of slavery and restoration of the Union achieved through the great sacrifice of the Civil War, Lincoln believed the nation had been born again, rededicated to the founding “proposition,” as Lincoln called it, “that all men are created equal.” Through this theme, Lincoln infused the war and the great sacrifice of the dead and wounded with meaning.

In his brief address, Lincoln never quoted directly from the Bible. Yet, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that he deliberately invoked biblical intonations, idioms, and themes for rhetorical effect. Sacred language and themes set a tone of solemnity, underscored the magnitude of the occasion, and emphasized the moral gravity of the message. Moreover, this rhetoric brought comfort and, perhaps, a prophetic voice to a people in the midst of a devastating conflict.