Scalia's Genius and His Curse

When our sensibilities were fed from different sources, it used to be said that, with spring, “the voice of the turtledove has been heard in the land.” But in these recent weeks the landscape has been filled with the sounds of “disinvitations” to speak and receive degrees at what used to be called our “better” colleges and universities. Colleges of the second rank may now be seeking to lift their standings by seeking out prestigious speakers to “disinvite.” The shock of this year has been that the protests have forced from the podium even figures of impeccable liberal stamp such as Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (at Smith College) or Robert Birgeneau, the former chancellor of Berkeley (at Haverford). What is apparently not worth noticing any longer—or any longer subject to indignation—is that these colleges have long since screened from their parade of honorees any notable figures on the conservative side.

When our sensibilities were fed from different sources, it used to be said that, with spring, “the voice of the turtledove has been heard in the land.” But in these recent weeks the landscape has been filled with the sounds of “disinvitations” to speak and receive degrees at what used to be called our “better” colleges and universities. Colleges of the second rank may now be seeking to lift their standings by seeking out prestigious speakers to “disinvite.” The shock of this year has been that the protests have forced from the podium even figures of impeccable liberal stamp such as Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (at Smith College) or Robert Birgeneau, the former chancellor of Berkeley (at Haverford). What is apparently not worth noticing any longer—or any longer subject to indignation—is that these colleges have long since screened from their parade of honorees any notable figures on the conservative side.

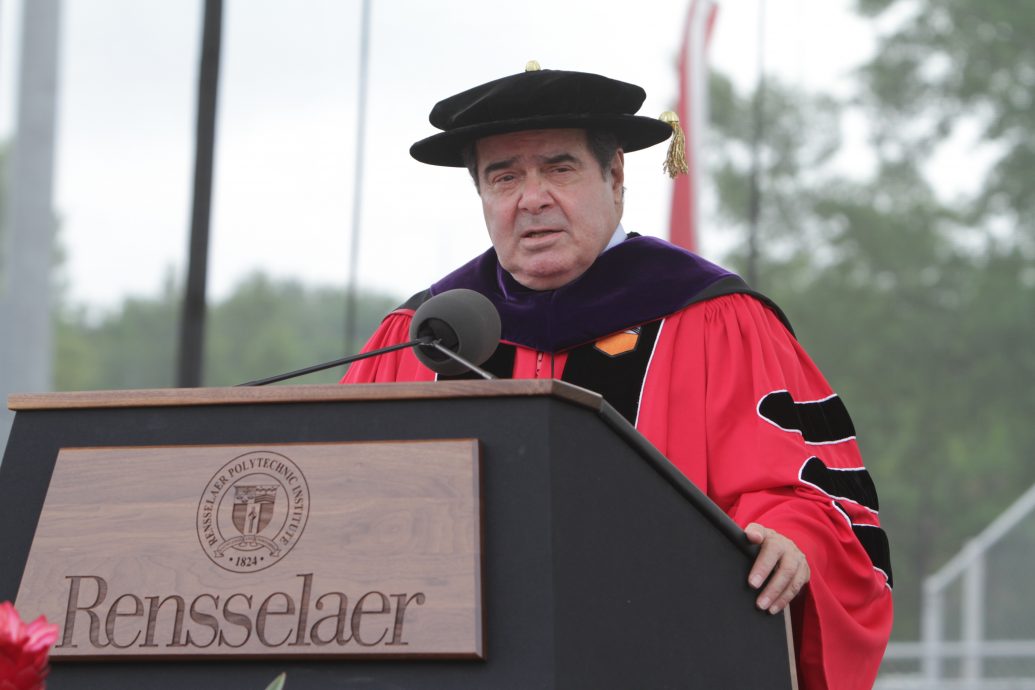

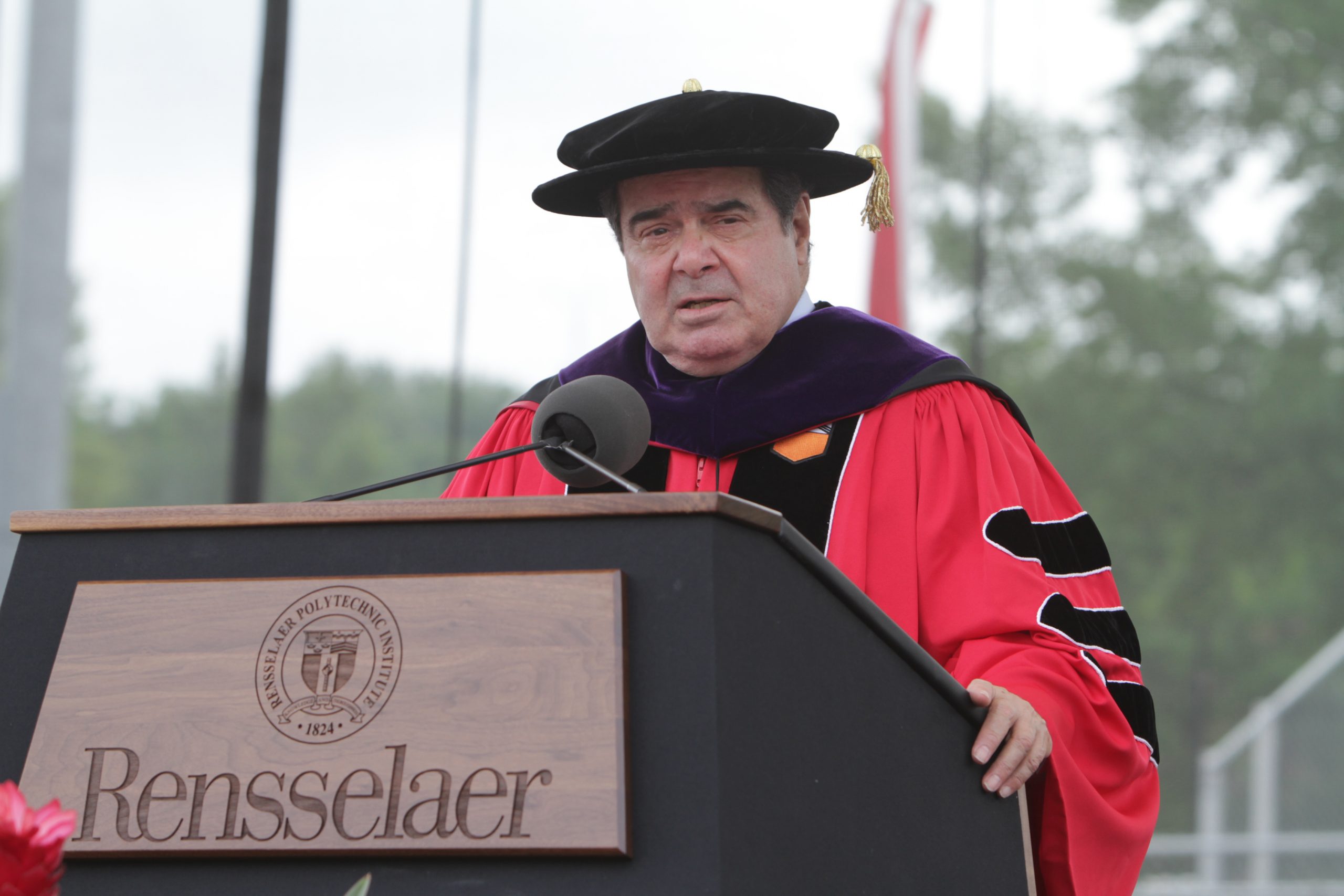

I heard once the president of an Ivy League college remark that his school couldn’t invite Clarence Thomas to campus without providing a “food taster.” One President of Amherst did invite Justice Antonin Scalia to offer a lecture, but 16 members of the faculty announced that they would not themselves attend his lecture, lest they legitimize his presence on the campus. Scalia did come, and as usual he won the hearts of many and impressed all. But there had been a threat on the part of students to stand with their backs to the speaker to show their disrespect. That spectacle was averted when conservative students invited the dissidents to hold a meeting, days later, where they could debate the propriety of inviting to the campus a sitting member of the Supreme Court.

For conservatives the Commencements have become the occasion in which we sit, in courteous silence, as honors are bestowed on people we would be far from commending to the students or the public, to put the matter gently. To put it less gently we are asked to pay homage to people whose policies and teaching we would regard as morally destructive. And yet, we preserve a decorous silence. In the current state of affairs, that is not a restraint that has to be observed by people on the Left. When it comes to religion and prayers at public schools, the Supreme Court years ago conferred a virtual lever for students, and perhaps even faculty, to purge from the platform words and speakers they find repellent. One of the ironies of the season is that the recognition has not broken through that there may be a “right” here that could be invoked by conservatives as well.

In Lee v. Weisman (1992) Justice Kennedy wrote for the Court in sustaining a young woman, graduating from a high school in Providence, Rhode Island, who felt put upon, coerced, by an invocation offered by a local rabbi. The “prayer” was as generic, non-sectarian, as one could devise, in acknowledging the God recognized by Christians and Jews, the same Creator mentioned in the Declaration of Independence. Apparently it was beyond Deborah Weisman and her family that they would show a certain religious tolerance themselves by sitting in silent respect, much as they might sit with a family saying grace. Justice Kennedy, writing for the Court, saw a critical coercion here as the ritual came to bear on a young person, for she could not apparently be expected to show her objection by declining to attend her own graduation. That was not a license that Kennedy was willing to accord, most recently, to the people who objected to prayers or invocations before the meeting of the local board in Town of Greece, New York. The non-believers, said Kennedy, were free to leave the room, and yet, “ should they remain, their quiet acquiescence will not, in light of our traditions, be interpreted as an agreement with the words or ideas expressed. Neither choice represents an unconstitutional imposition as to mature adults.”

But as Justice Scalia pointed out in dissent in the Weisman case, the telling comparison, in coercing students, was marked by the cases in which the children of Jehovah’s Witnesses were compelled to salute to the American flag. In West Virginia School Board v. Barnette, there was real coercion: for failing to render the salute, the students could be expelled, and their parents put in jail for failing to have their children in school. And yet, with the Weisman case, “coercion” could now be “psychological coercion”: a student could suffer embarrassment if she remained sitting or left the hall to avoid “complicity” in the prayer. She was “coerced” if she were simply compelled by convention to stand or sit in silent acquiescence.

What Scalia had the wit to see was that the combining of these cases—Weisman and Barnette—produced a result that was devastating if anyone bothered to put the pieces together and recognize the weapon being forged now. For the “right” articulated by the Court in the Barnette case was not confined to religion and prayers. Justice Robert Jackson framed the argument in a sweeping way: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation,” wrote Jackson, “it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.” The “right” here was a right not to suffer the imposition of a “political orthodoxy,” not merely the imposition of a creed that runs counter to religious convictions. If we take these decisions seriously, conservative students need not have to sit in acquiescence at a public university as the institution confers honors on people who seek, say, to defend the “right” to kill unborn children. The students might have a right now to purge from the program this imposition of a political orthodoxy they find deeply objectionable.

The Court had fashioned one of those rare “rights,” so exquisite that it extinguishes itself: The move to bar speakers from the podium is itself the imposition of a political orthodoxy, and those who oppose it would have ample grounds then for closing it down.

But why do we suspect that this lever will not be available to the conservatives? It has been Scalia’s genius and his curse that he sees, more clearly than some of his colleagues, just how the logic of their decisions will unfold. His consolation, in many cases, is that most of his colleagues and the public do not.