Natural law is not some theory hanging in the clouds, but an essential element of the very act of judging.

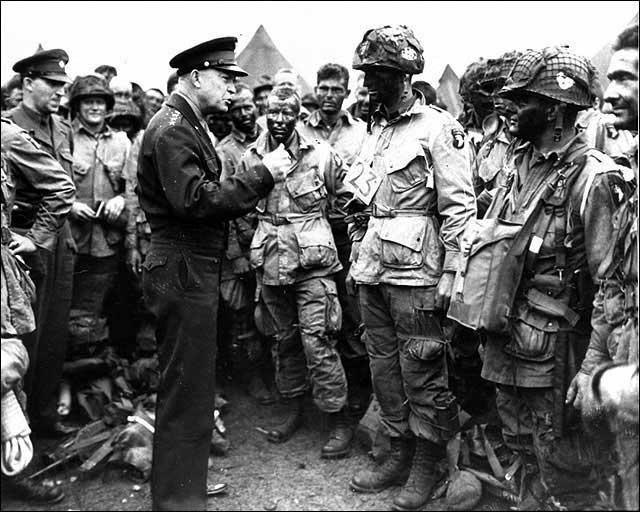

Ike’s Commitment to American Freedom

President Obama may have escaped the widespread carping at his West Point speech by bringing even greater embarrassment upon himself with the Bowe Bergdahl deal, and now the implosion of Iraq, but the recent D-Day celebrations impel us to revisit the offensive speech. There is much more here than the widely-noted hackery: e.g., “Those who argue otherwise—who suggest that America is in decline, or has seen its global leadership slip away—are either misreading history or engaged in partisan politics.” The captivating orator had become the whining demagogue many had previously perceived; the admired student body president appeared a petulant schoolyard bully.

President Obama may have escaped the widespread carping at his West Point speech by bringing even greater embarrassment upon himself with the Bowe Bergdahl deal, and now the implosion of Iraq, but the recent D-Day celebrations impel us to revisit the offensive speech. There is much more here than the widely-noted hackery: e.g., “Those who argue otherwise—who suggest that America is in decline, or has seen its global leadership slip away—are either misreading history or engaged in partisan politics.” The captivating orator had become the whining demagogue many had previously perceived; the admired student body president appeared a petulant schoolyard bully.

But what makes this West Point speech all the more galling is its audience and the contrast between him and the cadets and speakers who have preceded him. The Nobel Peace Prize winner himself opened up this contrast: “As General Eisenhower, someone with hard-earned knowledge on this subject, said at this ceremony in 1947: “War is mankind’s most tragic and stupid folly; to seek or advise its deliberate provocation is a black crime against all men.”[1] Eisenhower echoed this reflection throughout his public life.

The evocation drives us to the more notable now clichéd Eisenhower warning about the dangers of the “military-industrial complex”—perhaps the only thing many people know about him, other than his World War II service. We distort Eisenhower unless we see what preceded his warning about the complex’s

total influence—economic, political, even spiritual— … felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.

Despite its dangers, the military-industrial complex is “imperative.” What Eisenhower feared was not only corporate welfare and certainly not some conspiracy of elites for war profiteering but rather the triumph of instrumental, pragmatic reason of collective contracting over the individual’s intellectual curiosity.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead[2] of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

Eisenhower emphasizes the challenge for presidents: “It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system—ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.” He is not calling for an end to the “military-industrial complex” but rather for the public to be aware of “the supreme goals of our free society,” which include the “intellectual curiosity” of liberal education. The bureaucracy of modern society means the stifling of individual freedom. The soldier had a better appreciation of higher education at its best—after all, he had been for five years President of Columbia University—than former professor and Columbia graduate Obama .

Indeed, Eisenhower’s first speech as President presages these themes in his last speech. Focused on issues of war and peace, in Korea and against the Soviet Union, the First Inaugural declares

At such a time in history, we who are free must proclaim anew our faith. This faith is the abiding creed of our fathers. It is our faith in the deathless dignity of man, governed by eternal moral and natural laws.

This may be the last time an American President referred to natural law as a moral concept, certainly the last time in an inaugural address.

Natural law presents the duties as well as the rights of human beings and citizens. One of those duties is the acquisition of liberal education. The emphasis on duties as a part of rights strikes one as quaint, but this is the rhetoric not only of a soldier but of an American. After all, “Americans, indeed, all free men, remember that in the final choice a soldier’s pack is not so heavy a burden as a prisoner’s chains.” He would as well have said a slave’s chains.

By contrast, Obama’s Second Inaugural, which begins by quoting the Declaration of Independence, reduces the founding document to a part of an ongoing historical claim for ever-powerful government that creates new rights. Other Presidents since Eisenhower have made similar arguments, favoring rights but neglecting duties.

Eisenhower confidently speaks of liberty for, “We feel this moral strength because we know that we are not helpless prisoners of history. We are free men. We shall remain free, never to be proven guilty of the one capital offense against freedom, a lack of staunch faith” (emphasis added). Religion and freedom are at one in defying tyrants and alleged forces of history alike. Soldiers understand duty and sacrifice, the qualities natural law demands.

Russell Kirk’s quip that Eisenhower was “not a Communist, but a golfer” overlooks his political significance, which becomes evident when we contrast his speeches with those of his partisan predecessors Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. In his 1944 State of the Union Address Roosevelt compared conservative Republicans to Nazis (Heil Coolidge!):

One of the great American industrialists of our day — a man who has rendered yeoman service to his country in this crisis — recently emphasized the grave dangers of “rightist reaction” in this Nation. All clear-thinking businessmen share his concern. Indeed, if such reaction should develop — if history were to repeat itself and we were to return to the so-called “normalcy” of the 1920s — then it is certain that even though we shall have conquered our enemies on the battlefields abroad, we shall have yielded to the spirit of Fascism here at home.

In his successful come-back 1948 campaign, Harry Truman, justly honored for his European policies, matched Roosevelt in his comparison of the rise of Republicans with the fascist takeovers preceding World War II, as we see from this October, 1948 speech:

What are these forces that threaten our way of life? Who are the men behind them? They are the men who want to see inflation continue unchecked. They are the men who are striving to concentrate great economic power in their own hands. They are the men who are setting up and stirring up racial and religious prejudice against some of our fellow Americans.

I propose to state in simple, unmistakable language, just exactly how each of these three groups of men–working through the Republican Party, if you please–is a serious threat to the future welfare of this great Nation.

Eisenhower thwarted demagoguery such as this, while aggressively protecting civil rights in Arkansas and undercutting the demagogue McCarthy. His first inaugural contrasts with Roosevelt’s first, which calls on the people to sanctify his power, as though the country were invaded. Twenty years after Eisenhower left office Ronald Reagan would present an even greater contrast with FDR, by emphasizing the capability of people to govern themselves.

Of course, there is much to criticize in Eisenhower’s presidency—Suez, acquiescence in the New Deal, and horrific Supreme Court appointments, among them. But the General’s return to Washingtonian principles of the restraint of natural law is refreshing to consider during Obama’s presidency that seemingly knows no restraint on the domestic front and lacks any strategy in foreign policy.

Moreover, this is a presidency that is forging its own brand of demagoguery that recovers the successes of FDR and Truman, in slightly different guises. A proper response might begin with an appreciation of the wisdom of the old soldier, not least about “eternal moral and natural laws.”

[1] Note that this position is not pacifism. The Civil War is justified as a response to the provocation of secession.

[2] I do not preclude a reference to Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel. Cf. Walter Lippmann’s appreciation of Leo Strauss’s Natural Right and History in The Public Philosophy (1955).