If we take the Fourteenth Amendment to mean what Michael Rappaport and others argue, some strange consequences follow for resident aliens.

The Thirteenth Amendment as a Conservative Counterrevolution

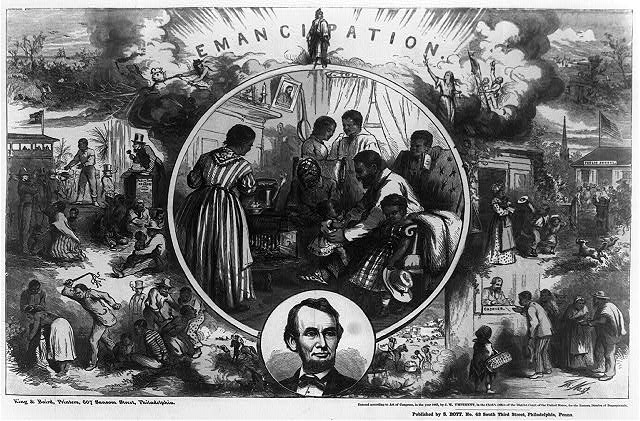

In “If Slavery Is Not Wrong, Nothing Is Wrong,” I proposed that the Civil War was fought to restore the original unity of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and that the Thirteenth Amendment, adopted in 1865, was the culmination of that colorblind restoration. In the antebellum period, opponents of slavery could not specify what would result once slavery was ended. Would free blacks have equal rights? Vote? Intermarry with whites? Thus did Stephen Douglas mock Abraham Lincoln.

The post-bellum answer of universal freedom nonetheless preserved much of the antebellum distinction between being anti-slavery and being anti-black. While Black Codes prevailed in Southern states, border and Northern states abolished their most extreme anti-black laws. The Thirteenth Amendment set in motion a logic that could have led to the republican (with a small “r”) abolition of much of this racist legislation. Not a merely historical matter, the debate over the Thirteenth Amendment reflects the inability of many originalist legal theorists to understand the essential role of the Declaration of Independence in constitutionalism. In reaction to some radical scholars who would twist the Declaration to overthrow the Constitution (suggesting, for example, that the Declaration compels a welfare state), some conservatives confuse matters further by overlooking the amendment’s inspiring political history.

An unhistorical originalism might even reinforce the narrow interpretation of this amendment found in the odious majority opinions in The Civil Rights Cases (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The contemporary debate fails to appreciate the radical change the Thirteenth Amendment, all by itself, meant for the entire Constitution in terms of federal and state powers alike. In fact, the liberal side of the debate over affirmative action preferences often allies itself with the logic of those majority opinions and finds inadequate the colorblind jurisprudence of Justice John M. Harlan, whose thinking on this point we attempt to revive.

Once the Thirteenth Amendment passed, the old enemies of freedom regrouped and tried to squelch this restoration of the Declaration. Even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Fourteenth Amendment represented a further attempt to specify and secure equal rights for the freemen. But this came with the flaws that Alexander Hamilton said would accompany the adoption of a Bill of Rights. As the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments specified various equalities, one could raise what other, unspecified rights remain unprotected, such as the right to hold office. Thus, the last-mentioned amendments lack full consequence unless we appreciate the robustness of the Thirteenth.

A key part of the legal strategy, as we see in The Civil Rights Cases, was to invent the conceit that the Fourteenth Amendment was restricted to political rights, not social ones (and thus segregation was not unconstitutional) or that “privileges or immunities” had little substantive content, or that discriminatory “state action” was required before the federal government could act.

This is what lies behind my assertion in my previous post that there is nothing authorized by the Fourteenth Amendment that cannot be legitimately accomplished through the colorblind Thirteenth, which makes the Congress the primary (albeit not the sole) enforcement authority. What the Fourteenth counts as “privileges or immunities,” “due process of law,” or “equal protection,” could all be legislated under the Thirteenth, in conjunction with the language of the original Constitution.[1]

Moreover, without slavery, what had previously appeared to be the Constitution’s compromises with slavery now become clearly republican and pro-freedom. For example, with emancipation, the apportioning of Representatives in the House requires fundamental adjustment—increasing the Southern states’ members and consequently their Electoral College votes.

The anti-slavery Constitution guaranteeing a “republican form of government” in the states (Article IV, section 4) and binding state judges under the supreme law of the land (Article VI) now becomes a revolution in federalism. The original Article IV, section 4 “privileges and immunities” clause was compromised by slavery: There must be a right to take a slave from Kentucky to Ohio, demanded slaveholders. Why wasn’t freedom universal?, responded slavery’s opponents. And now it was. Moreover, just as the Article V clauses dealing with the slave trade and equality of representation in the Senate are unamendable, the Thirteenth would be as well, making it as permanent as the Declaration of Independence.

Justice Harlan, while noting many of the constitutional changes outlined here, focuses on the meaning of the Thirteenth Amendment for the relations between the races.[2] He aptly summarizes and refutes the majorities’ attempts, in the consolidated 1883 Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson, to eviscerate the meaning of not only the Thirteenth Amendment but the entire Civil War.

The majority’s arguments concerning the Civil Rights Act of 1866 decisively altered the course of civil rights, determining, inter alia, the arguments that would be adduced for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Rather than using what many Republicans regarded as efficacious Thirteenth or Fourteenth Amendment arguments, the Democrats in 1963 and 1964 relied upon the Commerce Clause and held hearings on the bill in the Commerce Committee. Thus constitutional support for federal civil rights enforcement rested on whether a restaurant’s ketchup had moved in interstate commerce, not on whether citizens might not suffer treatment as an inferior caste.[3]

Harlan’s line of reasoning upheld the 1866 Act solely by relying on the Thirteenth Amendment. His Civil Rights Cases dissent begins: “The Thirteenth Amendment, it is conceded [by the Court], did something more than to prohibit slavery as an institution resting upon distinctions of race and upheld by positive law. My brethren admit that it established and decreed universal civil freedom throughout the United States”—not merely a negation of slavery. Containing a positive set of rights, the Thirteenth Amendment “alone obliterated the race line so far as all rights fundamental in a state of freedom are concerned.”

Harlan also reminds us of the key separation of powers concern in the Thirteenth. In a jab against the judicial usurpation of the majority opinion in Dred Scott, he wrote: “But it is for Congress, not the judiciary, to say that legislation is appropriate—that is, best adapted to the end to be attained. The judiciary may not, with safety to our institutions, enter the domain of legislative discretion and dictate the means which Congress shall employ in the exercise of its granted powers.”

In his more famous dissent in the Plessy case, Justice Harlan argues again for a robust Thirteenth Amendment. Justly noted for his ringing declaration therein that the “Constitution is color-blind,” Harlan shocks the readers of his opinion by also maintaining that:

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. The Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.

He was making an observation similar to Lincoln’s description of the Declaration as the “white man’s charter of freedom” (October 15, 1854). For Harlan would have his readers ask, what is the white race’s “great heritage and . . . the principles of constitutional liberty”? Was it not the document that states that “all men are created equal”? It may seem paradoxical, but the flaw of racial pride in Americans, when guided by reason and the proper motives, leads to racial equality and, what is more, to a republican America without classes and castes—an America following the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

But because of the vice of white racial pride (well described by Tocqueville), black pride must be calculating and make its case in public debate through Congress and law, not primarily through executive or judicial fiat. Unfortunately, in a manner not unlike the cotton gin’s technological boost to slavery’s expansion, the advent of evolutionary biology outraced the capacity for self-government; that new idea enveloped the flawed jurisprudence of the Plessy majority in the aura of science.

Thus, the Louisiana law at issue in Plessy, which commanded racial segregation in railway cars, was “a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution.” The “badge of servitude” here means a legal disability inflicted on people on account of their race. It perpetuates the servility of slavery on the basis of legally established classes.[4]

But, Harlan argues, the “recent amendment of the supreme law” inaugurated a new era that established “universal civil freedom, gave citizenship to all born or naturalized in the United States and residing here, obliterated the race line from our systems of government, and placed our free institutions upon the broad and sure foundations of the equality of all men before the law.” Thus, beyond abolishing badges of servitude, the Thirteenth Amendment, aided by the Fourteenth, ushers in an era of “universal civil freedom.”

The Thirteenth Amendment is colorblind and affirms the character of the entire Constitution as colorblind. Anyone can be a slave, though historically all the slaves then were black. The fact that there were large numbers of black slaveholders does not in any way mitigate the evil, though it does remind us that the spirit of tyranny dwells in all people.[5] We are reminded that slavery is condemned not only for what it does to the slave but for its debasing effect on the master.

Slavery is incompatible with modern republican government and citizenship. In the war against both tyranny and oligarchy and for republicanism, the Thirteenth Amendment abolishes the notion that some individuals or classes are born to rule, while other individuals or classes are born to be ruled. Thus, the Thirteenth Amendment, as much as the Fourteenth, forbids racial preferences. To move beyond racial slavery requires colorblind freedom.

Studying the Thirteenth Amendment takes us, as I’ve indicated, back to the Declaration, a charter for free men and women. We might thereby recover as well some degree of spiritedness in the form of patriotism. Americans’ being uninterested in the Civil War’s sesquicentennial is yet another sign of civic decay.[6] Weak democrats today know neither how to serve nor how to rule, and we don’t know equality. We become petty despots and the enervated “last men” of whom Nietzsche spoke.[7]

[1] My argument on the Thirteenth Amendment’s history draws on the older scholarship of Harold Hyman and William Wiecek, Equal Justice Under Law: Constitutional Development 1835-1875 (1982) and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic (2001). Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2001) and James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (2013) are essential recent reading. Note as well the work of Akhil Amar.

[2] I will limit discussion of Harlan’s opinions to the Civil Rights and Plessy cases.

[3] For the contemporary application of the Civil War Amendments to the Civil Rights debate, see Hugh Davis Graham, The Civil Rights Era (1990).

[4] See Jennifer Mason MacAward, “Defining the Badges and Incidents of Slavery,” 14 University of Pennsylvania Law School Journal of Constitutional Law:3(2012). She would restrict the meaning of badges and incidents but is uncertain how restrictive she might reasonably be. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1666967

[5] Larry Koger, Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860 (1985) is a meticulous study of the black owners of slaves. There were Indian slaves, as well as Indian slaveholders.

[6] Cameron McWhirter, “For Civil War Buffs, 150-year anniversary has been disappointing so far,” Wall Street Journal, April 10, 2014, A-3.

[7] Compare Obama’s illiberal appeal to the Declaration in his Second Inaugural, January 21, 2013: “Being true to our founding documents does not require us to agree on every contour of life. It does not mean we all define liberty in exactly the same way or follow the same precise path to happiness. Progress does not compel us to settle centuries-long debates about the role of government for all time, but it does require us to act in our time. For now decisions are upon us and we cannot afford delay. We cannot mistake absolutism for principle, or substitute spectacle for politics, or treat name-calling as reasoned debate. We must act, knowing that our work will be imperfect.” Though arguments over the Founding might be good intellectual exercise, they should not affect the way we act, however “imperfect” our actions may be.