Arms and the Several States

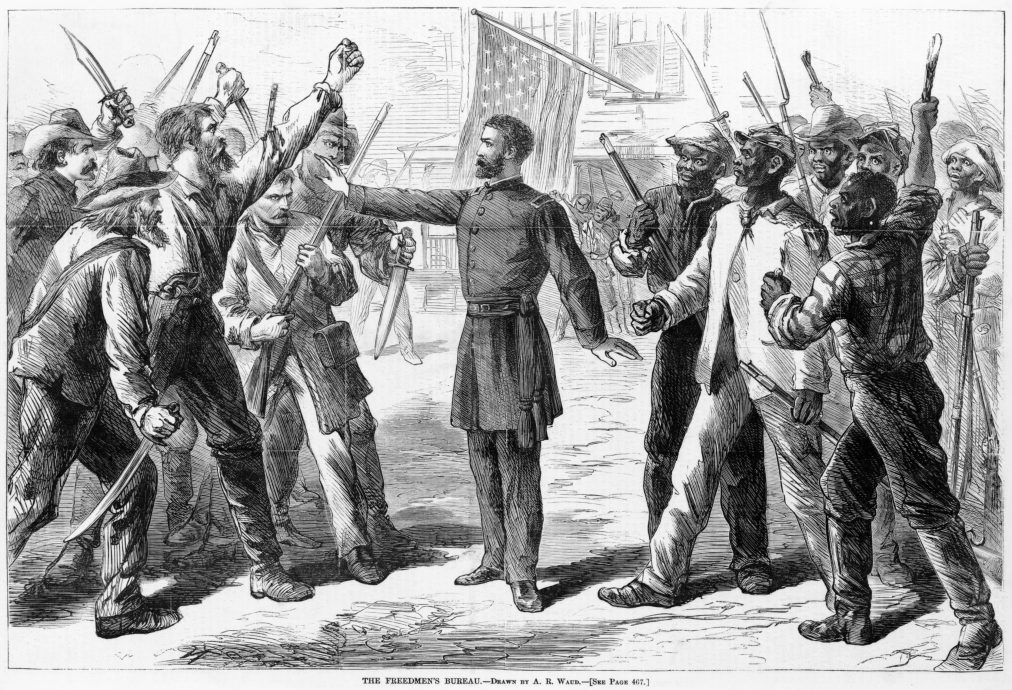

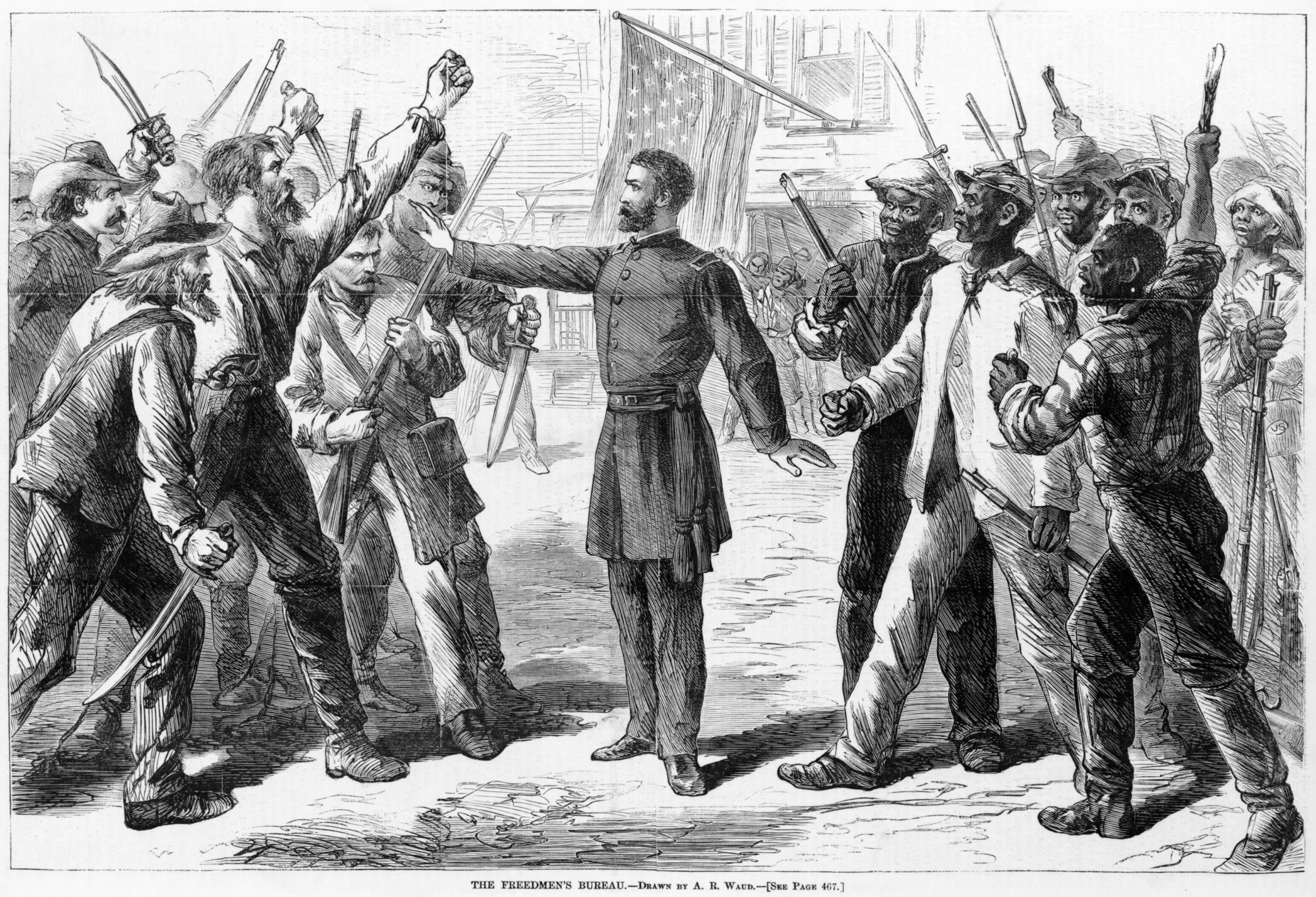

A Bureau agent stands between armed groups of Southern whites and Freedmen in this 1868 picture from Harper’s Weekly.

My last post discussed how John Paul Stevens, late of the Supreme Court, and author Michael Waldman advance a stingy, substantively empty view of the Second Amendment by ignoring the Constitution’s framework of limited, enumerated powers. That critique, of course, only goes to federal authority. The right to arms enforceable against the states rests on the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment is especially important to citizens of the eight states that do not have explicit right-to-arms provisions in their constitutions. And for our purposes here, it is important for the other glaring flaw that it reveals about the Stevens/Waldman methodology.

The evidence is overwhelming that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to guarantee former slaves the rights of American citizenship, starting with the guarantees of the first eight amendments to the Constitution, including an individual right to keep and bear arms.

Almost as soon as the shooting war stopped, Southern governments attempted to establish de facto slavery through a variety of state and local laws. Racially targeted gun prohibition was a common theme of these Black Codes. The freedmen’s concern was having arms for private self-defense and decidedly not about propping up the militias of the states recently in rebellion. Indeed, those state militias were often the enforcers of the Black Codes, so they were among the hazards Blacks needed to arm against. Even before the war’s end, the dynamic was plain. Witness President Lincoln’s instruction in the Emancipation Proclamation: “I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense.”

In 1866, the Second Freedman’s Bureau Act explicitly guaranteed to freed slaves “the constitutional right to bear arms” as a block against the racist gun prohibitions in the Black Codes. The Freedman’s Bureau Act also charged the occupying army with protecting the freedmen’s individual rights, including the right to arms.

Union Army officers and Freedmen’s Bureau agents worked to protect Blacks’ right to arms for self-defense and testified before Congress about the importance of vindicating this right. Black newspapers widely distributed the orders of the occupying army guaranteeing Blacks the constitutional right to arms for self-defense. Newly formed Black political organizations and state conventions filed numerous petitions with Congress pleading for protection of their right to arms for individual self-defense. In a May 1865 speech in New York, the great Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass lamented that “the Legislatures of the South can take from [the freedmen] the right to keep and bear arms” and that the work of the abolitionists was not finished until that right was enforceable against state governments.

These and other infringements on the basic rights of citizenship fueled the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. Senator Jacob Howard (R-MI) introduced the amendment by explaining that its “great object” was to “restrain the power of the states and compel them in all times to respect these great fundamental guarantees secured by the first eight amendments of the constitution, [including] the right to keep and bear arms.”

Justice Clarence Thomas’s powerful concurrence in McDonald v. Chicago (2010) explains how the Fourteenth Amendment aimed to repair the damage of the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which denied Blacks the privileges and immunities of citizens. Dred Scott was candid about what was at stake, declaring that if Blacks were deemed citizens they would have “the right to keep and carry arms wherever they went.”

Concurrent with the Fourteenth Amendment debate, Congress also passed legislation abolishing the Southern state militias. This was necessary, said one of the sponsors, because the state militias had been used to disarm the freedmen. The Supreme Court underscored the point in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), explaining: “Needless to say, the claim was not that blacks were being prohibited from carrying arms in an organized state militia.”

This is just a sampling of a story so rich that it would fill a book. In fact, it has filled several, including my Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms (2014); Stephen P. Halbrook’s, Freedmen, the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Right to Bear Arms, 1866-1876 (1998); Charles E. Cobb Jr.’s This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (2014); and Akinyele Omowale Umoja’s, We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement (2013).

So what do militia-fixated critics of the right to arms have to say about all this? Well, not much. Because if you aim to neuter the right to arms with claims that the amendment is only about militias, you really do have to ignore the Civil War, Reconstruction, the postwar amendments, and indeed most of the 19th century (including antebellum state court decisions holding that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to arms enforceable against the states).

Ironies abound here. Most cutting is that people who lean heavily on the Fourteenth Amendment to support rights that they like, avoid it like kryptonite when it comes to the constitutional right to arms. Someone quipped that this is constitutional interpretation, buffet-style. Justice Stevens’ dissent in McDonald is a prime example of this. It extols privacy and reproductive rights grounded in the Fourteenth Amendment, but disparages the armed self-defense right that will keep you alive to enjoy all the others.

For many years, critics chided the academy, the government, and society at large for rendering Blacks invisible within the American story. That criticism invoked our strongest moral invectives. Recently, both Stevens and Waldman have actually used the word “fraud” to disparage the constitutional right to arms. So where is the outrage when supposed champions of civil rights blithely dismiss the struggles of the first generation of black citizens and the enduring lessons surrounding the Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of the individual right to keep and bear arms?