Return to the Barbaric

The President’s use of executive power outside and above the bounds of the Constitution is well known at this point. In policies ranging from the railroading of creditors in the auto bailouts, to Obamacare by waiver, eliminating key work provisions in the 1996 welfare reform legislation, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and to the informed suspicion that he will unilaterally legalize 5 to 6 million illegal immigrants, this President has entered a new realm of abuse of power. Resulting from the stress he’s placing on our constitutional order have arisen significant interventions that attempt to underline how and why we have arrived at this new dimension of executive power, even in the case of Congress there is an attempt to reclaim its authority, if only in a pusillanimous manner.

Congress, with its quiver of constitutional arrows, perfectly designed to hobble such discretionary enthusiasms, has chosen to assert itself with a lawsuit (the highest form of politics in our age) alleging that Obama has made them constitutionally irrelevant. But that is a game for two, isn’t it? This suit is a prayer to the Federal courts, made in the hope that, ultimately, the Court will do for Congress what it won’t do for itself, namely, reassert the limits of the Constitution on the executive branch. What exactly the Court would order the President to do and how it would effectuate the outcome are both difficult to identify.

Chris DeMuth has put together a series of lectures and essays that grapple with the inexorable rise of executive power in domestic policy. DeMuth’s arguments here are worth considering in detail, as is his call for a return to a parochial congressional-driven politics.

From Philip Hamburger’s striking new book Is Administrative Law Unlawful? we learn that the rise of administrative power is the revival of something quite old–monarchical prerogative power–which spells the end of our constitutional government. The prevention of such discretionary executive power was precisely what the Founders tried to accomplish with the Constitution’s strictures and in the many state constitutions they drafted and ratified. Hamburger’s work, while obviously not aimed at the current White House occupant, helps us to understand that the present abuse of executive power through and with the administrative state has been generously prepared over many decades. Nothing new here, just the willingness of the president to press to its most logical extent every advantage the regulatory state affords him.

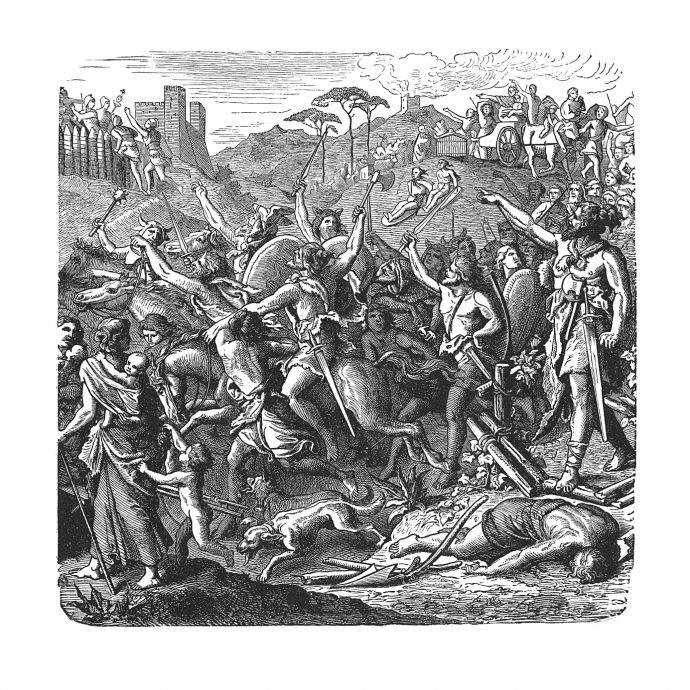

What if the symptoms of disorder, however, are found in even deeper sources that require different thinking? In this president’s willingness to rule by waiver, edict, and order he asserts a private right of rule on behalf of a progressive matrix of race, class, and gender that fundamentally undermines the public commitment of constitutional government. In this, our president is recalling the barbaric exercise of power. What do I mean? Barbaric government is not defined by lack of sophistication, nor by human rights abuse, rather its nature is in the assertion of rule by and for private interests exclusively. A barbarian exercises his reign for his private interests, and is unable to distinguish between public space and its claim on his loyalties and duties and the private realm and its separate claim on his interests. The two mix or co-determine each other. The personal is the political.

The eccentric and unfortunately somewhat forgotten 19th century American thinker Orestes Brownson located western constitutionalism’s initial victory over barbaric political rule in the Greek polis and in the Roman Republic. Athens, he states “introduced the principal of territorial democracy,” and subdivided power “into demes or wards.” The principle demonstrated was the “loyalty of all citizens” to Athens, and not to a particular ruler or ruling group. The Senate body in Rome organized the undifferentiated mass into a body politic that was governed by public rule. Only those heads of households that were “tenants of the sacred territory of the city, which has been surveyed and marked by the god Terminus,” could govern in the Senate. Their power was only public power or political sovereignty. Brownson formulated that the city or state takes the place of the private proprietor, and territorial rights take the place of purely personal rights.

Barbarian in the original sense is unknown, Brownson concluded, but if we look to the Greeks and the Romans, we know that they never applied it to all foreigners. The term was meant as a political category:

to designate a social order in which the state was not developed, and in which the nation was personal, not territorial, and authority was held as a private right, not as a public trust, or in which the domain vests in the chief or tribe, and not in the state; for they never term any others barbarians.

The epitome of barbaric rule was feudalism where the entire order was predicated on private ownership.

The feudal monarch, as far as he governed at all, governed as a proprietor or landholder, not as the representative of the commonwealth. Under feudalism there are estates, but no state. . . . The whole theory of power is, that it is an estate; a private right, not a public trust. It is not without reason, then, that the common sense of civilized nations terms the ages when it prevailed in Western Europe barbarous ages.

American constitutionalism, Brownson argued, with its division of powers vertically and horizontally, was centered on the principle of freedom. To effectuate this principle required a justification for both the authority that was due individual liberty and the rightful loyalty the citizen should give the constitutional order. The legitimacy of this order inhered in the shared enterprise of representative government attached to borders, state and national, which permitted direct accountability of rulers and ruled occurring across multiple layers of government. Due regard for self government would ensure that freedom flourished for individuals and their private forms of association.

Brownson’s principle helps us understand the powerful distinction between a personal right of rule versus a public right of rule or what he calls “territorial rights.” Interestingly, Brownson argued that the rise of majoritarian government in Europe in 1848, the supposed year of liberation, was the reincarnation of barbaric power. Races, ethnicities, and nationalities within Europe had expressed and claimed their control over territory, independently of their actually possessing legitimate authority to create and define the new territory as their own. Solidarity of a pre-political association, in this case, a perceived group identity, in some cases violently trumped the historical evolution of right and law and borders. So we see that even the claim of public right can actually mask a much deeper will that desires to express power for pre-political interests, ones that attach to a group because of race or ethnicity. In different forms, the tribe returns to power with its chief ruling in its name. In short, we have an expression of power that is barbaric, tribal, i.e., private, expressions that cannot be interrogated or disciplined by deliberation.

Where do we stand?

Our President’s fealty is obviously not to the Constitution and its principles that limit power. Where does it rest? We see that his loyalty to the law comes through its ability effectuate the private power interests, the pre-political group rights, call it the 21st century’s version of the friend/enemy distinction. Members of the illiberal literati might reply that these are public ordering principles, not private ones. For example, we are trying to end gender inequality so we must requisition insurance companies and employers to pay for contraceptives and abortions. Thus the charge of political barbarism fails. But the claim of public rule is that it is exercised in the form of a shared enterprise regarding policy subjects that can be rationally debated. Surely, a first requirement in the assertion of an interest is that it be open to deliberation, to “dry political argument.”

But we see that the claims of the progressive matrix that guide this president like none previous are impervious to rational deliberation. These identities resist being the subject of debate. If my sole claim as a public individual is racial or gender identity or being part of a class, then where exactly is there room for compromise? To interrogate these identities, to question them as a basis for law, for rights, is to seemingly deny that the person or group making them has public validity. When that point is reached Congressional power, the branch situated to rule by deliberation, compromise, and shared agreements becomes irrelevant. Instead, we enter Carl Schmitt land or the need for government by executive, government by discretionary enforcement. Our friends are obvious to us, all that remains is “to punish our enemies.”

The question for free men and women, for Americans, is why have we let this come to pass?