Shocked, Shocked that Federalism is Occurring Here

The New York Times has been running a multi-part story—with countless additional internal links—on the connections between (Republican) state attorneys general and industry groups and their lawyers and lobbyists. There’s lots of wining and dining in fancy places to gain and maintain corporate access to state AG’s when it’s needed—more often than not, to deal with this or that multi-state investigation and prosecution. Also, the energy industry in particular has made common cause with state AG’s in fighting the Obama administration’s climate change agenda. The article series is quite good in a Times-ish way—informative to the point of exhaustion, self-congratulatory (“We intrepid reporters unearthed this information on the internet! And through open records requests!”), and slightly paranoid.

“Energy Firms in Secretive Alliance With Attorneys General,” blares the headline. The accompanying picture shows Oklahoma AG Scott Pruitt at a conference, underneath a giant Peabody Energy sign. Secretive? The AGs and the energy guys file federal lawsuits together and appear at joint press conferences. Far from running a cloak-and-dagger operation, General Pruitt and his colleagues boast about their efforts to protect the industry. Weird if you think of electricity as a satanic force. Totally sensible if you represent a state where the stuff is produced—and in turn generates the middle-class incomes the administration has been trying to subsidize into existence.

That said, the Times series does call attention to several salient insights—foremost, the somewhat strange emergence of state AG offices as key veto and opportunity points in American politics. How did that happen?

The definitive treatment is a forthcoming book, credited by the Times, by Marquette PoliSci professor Paul Nolette. I know what’s in the book (“Federalism on Trial”) because it’s based on the author’s award-winning dissertation. I served on his Boston College dissertation committee, and I confirm that this is a very impressive piece of work. Among other things Mr. Nolette was a lawyer before he repented; thus, unlike the quants who now dominate the profession, he comprehends all the litigation stuff.

Long story very short (the snark is mine): this wasn’t started by corporate honchos but by their foes. When the federal government embarked on de-regulation way back in the 1980s, pro-regulatory constituencies migrated to the states. State tort law and prosecutions under state and federal law became substitutes for regulation, and state AGs formed a symbiotic alliance with the plaintiffs’ bar. The corporate fixers are just fighting back. And note that the deck is stacked against them. The trial lawyers need only a single state AG to unleash a prosecutorial firestorm on a national basis. To stop it, the corporate guys and gals have to run the table.

The AG-trial bar alliance has proved lasting to this day. For every corporate-AG shindig, there’s an equally glitzy trial lawyer event. You can always tell the AGs from the private lawyer crowd: they’re the only ones without private planes. But in all other respects, the AGs are just trial lawyers with a badge. One of theirs went to jail for a “pay to play” arrangement; others found legal ways of renting their offices to the plaintiffs’ bar. Nowadays, state AGs file consumer mass actions when, where, and because the federal Class Action Fairness Act bars class actions. (The Supreme Court has blessed that maneuver.) For another example, I have through fearless sleuthing uncovered a letter from sixteen state AGs to CFPB Director Richard Cordray, imploring him to regulate consumer financial contracts (such as credit card agreements) that mandate arbitration and bar class actions. It reads like something from the Jamaican Tourism Bureau: please Mr. Cordray come govern us, and set our trial lawyers free.

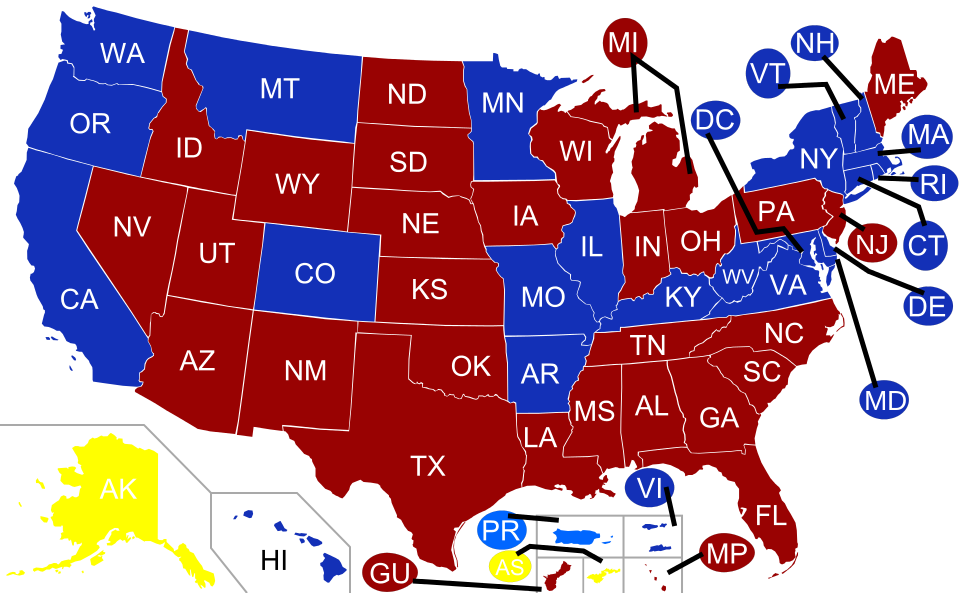

Obviously—and this is the second point the Times would emphasize if it understood what it’s covering—these aren’t the same state AG’s. The pro-regulatory AGs come from the usual places—California, Illinois, New York, and so on. The pro-business, pro-energy AGs hail from equally predictable places: Texas, Oklahoma, West Virginia, etc. As I’ve insisted before, contemporary federalism isn’t about “the states (generically) versus the feds.” It’s between and among blocs of states—one that depends on the feds, and one that wants them to go away. The National Association of Attorneys General no longer has any serious cohesive program or interest. Conversely, cooperation within the partisan blocs has become increasingly organized and routinized.

That resurgence of political sectionalism—third point—has been hastened by a number of forces and events. The fight over the ACA was a game changer, not only in its own right but also by catalyzing state cooperation. Then, there’s the head-on collision between a fantastic energy boom (just about the only thing that’s gone right with the economy) and the administration’s war on energy. And then, there’s the administration’s and, up to now, its Congress’s resolve to govern by fiat rather than legislative compromise. Once upon a time, energy states could rely on Senators and Representatives to protect their interests; now, not so much (go ask Mary Landrieu, who ended up under Senator Reid’s bus). So who are you going to turn to? State AG’s, and their Solicitors General.

There are reasons to be a bit nervous about the Times’ attention. For one thing, this is now the official “progressive” story line: if the administration’s climate change rules or for that matter its ACA rules go down in the Supreme Court, it’s a conspiracy (and John Roberts is its tool). For another thing, this is a very high-stakes confrontation. Lots of money is involved, and lots of people are involved; sooner or later someone—likely one of the Beltway bandits who hang around this scene—will do something stupid even if the Times hasn’t found it yet. On the whole, though, this is a good problem to have. The good AGs have attracted attention not because they’re on the take but because they’re effective.