Life and Literature, American Style

In her 2003 book, Reading Lolita in Tehran, Azar Nafisi demonstrated how the written word trumps tyranny. Nafisi interwove sometimes harrowing reminiscences of the Islamic Republic of Iran before and after the 1979 revolution with discussions of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, Henry James’s Daisy Miller, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. These and many other works were mined for their poetry of expression and their characters’ defiance.

It was a masterful exposition of events in Iran built on close reading of the great Western books—books read furtively and at the risk of punishment by the regime. Nafisi, while a seasoned teacher and literary critic when Reading Lolita in Tehran came out, was not well-known. But this debut account from one who had experienced tyranny firsthand struck a chord: it won a place on the New York Times best-seller list for over 100 weeks, and has been translated into over 30 languages.

It chronicled Nafisi’s personal story, including her partly American education, her time as a professor at the University of Tehran until her expulsion because of her refusal to wear a veil, the fate of her family and close friends, her peregrinations to various teaching posts in Iran and, most important, her courageous decision to hold a book discussion group with students in her home, in secret. It was an illegal a book club that, in the two years of its existence, provided the inspiration for her ground-breaking book. She emigrated to the United States in 1997 and became an American citizen in 2008.

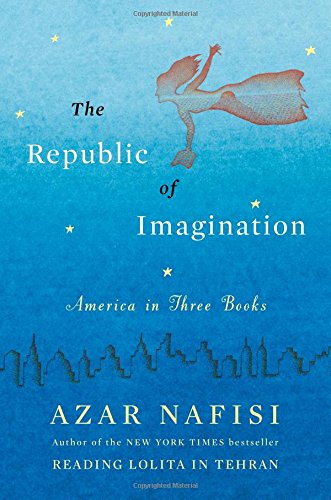

With The Republic of Imagination: America in Three Books, Nafisi applies a similar literary structure to considering how heroes come to the fore in uneasy times. This time, her anchoring works of fiction are Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt and Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, among other works by these authors and others.

In the introduction, she sets the tone by quoting the poet Joseph Brodsky’s 1987 Nobel Prize acceptance speech:

Though we can condemn the material suppression of literature—the persecution of writers, acts of censorship, the burning of books—we are powerless when it comes to its worst violation: that of not reading the books. For that crime, a person pays with his whole life, if the offender is a nation, it pays with its history.

Books and reading have played a singularly defining role in Nafisi’s life, and it is the concept of the suppression of books and reading in Iran and elsewhere that drives The Republic of Imagination. However, in this wide-ranging survey of the challenges and consolations that literature offers, it is worth noting that the book’s message is less polemical than celebratory and less political than simply urgent.

There are the heroes we have, and the heroes we need—and one of them, she argues, is the fictional hero that she and her friend Farah discovered in childhood: Huck Finn. Nafisi includes her conversations with Farah, an Iranian exile who becomes terminally ill with cancer, as they return to their early fictional hero for inspiration and in order to cope with the vicissitudes of life. (The Republic of Imagination is dedicated to, among others, the late Farah Ebrahimi.) Huck, writes Nafisi,

gave us vital clues as to the kind of Americans we wanted to be. He reminded us—and this was something I kept coming back to—that at their best, American heroes are wary of being overcivilized, that they carve out their own path and look to their heart for what is right and just.

If Huck is given center stage and a fresh reading, he is also a founder of what the author calls her republic of the imagination, a place where “founding documents were written by poets and novelists.”

George Babbitt comes under a different kind of appraisal. His god is business, and while Nafisi does not condemn the character, there is no hiding her negative feelings about the restlessly striving realtor from the fictional Zenith, in the fictitious Midwestern state of Winnemac. Nevertheless, she does aver that Lewis’s “genius was in capturing the spirit of modern advertising when it had not yet come to dominate the American landscape and define the soul of a nation.”

The takeaway from her Babbitt section, one that most readers will not soon forget, is her blistering appraisal of the all-too-real Common Core State Standards now being put forward by the U.S. Department of Education. One could ask how an attack on Common Core fits in with more sublime observations about literature and life, but in this free-associative, thinking person’s guide to what matters in life, it is no surprise to find this:

Suddenly the goal of school was no longer to prepare children for the world and to turn out fully formed and informed citizens, but to create employable, college-worthy test-takers capable of passing multiple choice math and English tests.

Not a virtue.

The villains in Nafisi’s world are orthodoxy and conformity (two things abundantly present in the Common Core). Huck is no villain and certainly no conformist, but it is the book’s discussion of Mick Kelly, the protagonist of McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, that gives fresh meaning to the necessity of nonconformity and a particularly American brand of loneliness that, growing as it does out of the struggle for the right to be one’s own person, ultimately signals strength not weakness.

And there is, besides, a telling observation that Nafisi got from Richard Wright. In a 1940 issue of The New Republic, Wright compared McCullers to William Faulkner and said:

To me, the most impressive aspect of The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is the astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern fiction, to handle Negro characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race.

Azar Nafisi approaches the issues of race unflinchingly (best seen in the book’s stunning Epilogue on James Baldwin that is more main event than coda) even as she elucidates how freedom, individuality, and purpose depend on books and their heroes. Writing with clarity and eloquence, she offers observations about why—especially in these fraught times—books matter. She is a courageous defender of that proposition, and a trustworthy guide to the works that will most repay the efforts of the receptive reader.