The Enduring Tension That Is Modern Conservatism

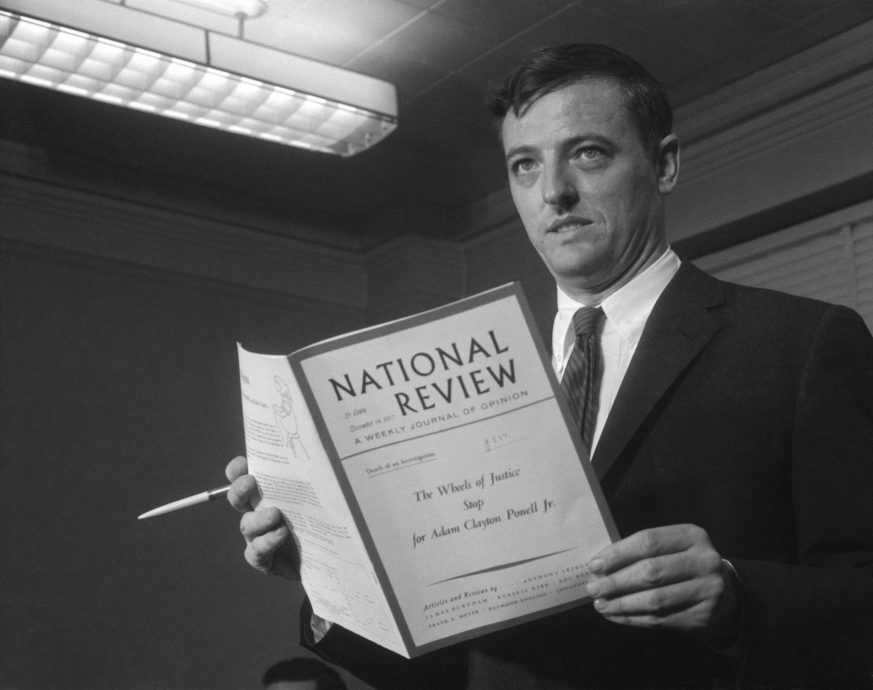

The preeminent conservative intellectual forum called the Philadelphia Society devoted its recent meeting to exploring the roots of its philosophy, especially conservatism’s mid-20th century rebirth at National Review magazine under William F. Buckley, Jr. and Frank Meyer. Discussants could not ignore an important fact: that the modern conservative movement was born bearing a revealing quirk.

To free American conservatism of its image as a defense of the status quo, new labeling was essential. Meyer, who had come on as National Review‘s literary editor in 1956, ruminated upon a philosophical grounding for the movement. In 1962, editor Brent Bozell characterized what Meyer had come up with as “fusionist conservatism” and, despite that this was supposed to have been a criticism of the movement’s (and the magazine’s) apparent dualism, the “fusionist” tag somehow stuck.

It took Buckley, for his part, about two decades to fully embrace it. Even Meyer, who was most identified with fusionism, preferred the word “tension” or the more technically correct “synthesis.” Of course trying to call a doctrine “synthetic” hardly worked in an era when plastics were the latest, and much discussed, innovative technology. The adjective had come to mean “artificial.”

So the brand name became fusionist-conservatism. It was clumsy. But the most important conservative intellectual institutions could not avoid it, including the Heritage Foundation, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, the Philadelphia Society, and the Conservative Political Action Conference, among other organizations. The movement’s leading politician, Ronald Reagan, was not afraid to use the technical term. Reagan gave the honor and credit to Frank Meyer for fashioning the “vigorous new synthesis of traditional and libertarian thought” that “is today recognized by many as modern conservatism.”

In his first speech to fellow conservatives upon becoming President, Reagan specified what this fusionism was. After listing “intellectual leaders like Russell Kirk, Friedrich Hayek, Henry Hazlitt, Milton Friedman, James Burnham, and Ludwig von Mises” as the ones who “shaped so much of our thoughts,” he discussed at length someone not on that list:

It was Frank Meyer who reminded us that the robust individualism of the American experience was part of the deeper current of Western learning and culture. He pointed out that a respect for law, an appreciation for tradition, and regard for the social consensus that gives stability to our public and private institutions, these civilized ideas must still motivate us even as we seek a new economic prosperity based on reducing government interference in the marketplace.

The whole idea of a synthesis of individualism and culture, of libertarian and traditional thought, emerged rather than being set beforehand. A fusion between tradition and freedom as the central idea of the American Constitution and experience, indeed of all Western civilization, simply blossomed under the creative tension among the editors at National Review in producing a coherent magazine, month after month, year after year until the concept jelled.

Even from the beginning, fusionism was used in two senses.

First, it was viewed as political, as the coalition that built upon the magazine’s readership to bloom in the electoral campaigns of Barry Goldwater and Reagan. As political scientist Aaron Wildavsky later noted, linking traditionalists and libertarians creates a powerful coalition between two of the four basic political types. (His other two were “egalitarian” and “fatalist.”) Indeed, Wildavsky found this the most likely democratic governing coalition. And America’s new political movement did become enormously successful. It nominated Goldwater, and both nominated and elected Reagan. Yet, this coalition would, over time, fuse so many different interests under the term “conservatism” that its extreme diversity came to undermine its intellectual integrity.

The second sense of the term—the one Reagan identified—was philosophical. Intellectually, fusionism represented a synthesis, at the center of which was the individual person. As Professor Larry Siedentop details in his 2014 book Inventing the Individual, notwithstanding minor earlier stirrings in Epicureanism and Stoicism, the idea of the morally equal individual arose for the first time in history under St. Paul (and Jesus), who in a major departure from past beliefs placed the individual rather than the family at the center of social and political life. This new individual was free to reject the family and traditions generally and yet was formed by them, existing therefore in a constant state of moral tension between them. The individual, by becoming the deciding moral agent, leaned toward freedom or toward tradition in concrete situations, but did not set either one as the pinnacle of a fixed ideological hierarchy.

The only resolution of Paul’s synthesis of Greek rationality and Jewish tradition was in a Jesus whose kingdom was not of this world. This metaphysical unity in concrete diversity, so to speak, was further elaborated early in the 5th century in Augustine’s City of God where, even in the godly regime, human “peace is not full so long as he is at war with his vices.” Accomplishment in this world is never “secure, but full of anxiety and effort.”

All Western history became engaged in resolving this tension, producing a dynamism that gave the West its creative and dominating culture. Competing perspectives demanded resolution of the tension through unitary ideologies: through idealized republics, this-world empires, Divine Right monarchies, Jacobin revolutionism, militaristic nationalism, Nazism, communism, socialism, or today’s secular Progressivism.

Meyer’s philosophical fusionism, then, is sweeping. It posits a concrete history from the caves of Lascaux, through Athens and Jerusalem, to Jesus and St. Paul, to Augustine and the Roman Empire, to Europe and Thomas Aquinas and John Locke, to America and the Founders—to its dislodgment by Progressivism in the early 20th century, followed by a rejuvenation that began in 1944, when F.A. Hayek came out with The Road to Serfdom, a book taken to heart by Buckley and Meyer.

The modern challenge was summarized by Hayek in his final work, Law, Legislation and Liberty (1973):

I believe people will discover that the most widely held ideas which dominated the twentieth century, those of a planned economy with a ‘just distribution,’ a freeing ourselves from repressive and conventional morals, of permissive education as a way to freedom, and the replacement of the market by a rational arrangement of a body with coercive powers, were all based on superstitions . . . an overestimation of what science has achieved . . . in the field of complex phenomena, where the application of the techniques which proved so useful with essentially simple phenomena, has proved to be very misleading . . . What the age of rationalism—and modern positivism—has taught us to regard as senseless and meaningless formations due to accident or human caprice [that is, traditions] turn out in many instances to be the foundations on which our capacity for rational thought rests.

Hayek’s list of wrongheaded ideas may seem strange to traditionalist conservatives seeking “just distributions”; equally so to libertarians demanding to be “free of repressive and conventional morals.” But Hayek viewed both tradition and morality as the necessary “foundations” of a free society. The way to recovery was through law that was based on custom. That is to say that laws and customs achieved, through the free means of markets, the voluntary organization and decentralization that were needed to re-energize Western civilization.

The term fusionism has been problematic from the beginning, but the synthesis underlying it has been remarkably persistent. It has reappeared under many different guises, most recently the new book by the young journalist Charles C.W. Cooke. Cooke’s Conservatarian Manifesto (which Ron Capshaw reviewed for Law and Liberty) argues for a new blend of conservatism and libertarianism because both are necessary to return America to its constitutional roots. The irony is that the author is a writer for National Review who seems unaware that the founding editors of his publication formulated his “new” idea a half-century earlier, much less that his ancestors began developing it 2,000 years before.

Whether in the wake of a declining Rome; in a post-Charlemagne Europe; at the American Founding; in the post-World War II revival under Hayek, Buckley, and Meyer; or for today’s young writer looking for a solution to modern challenges, the fused inheritance of freedom and tradition somehow forces its way through as the most reasonable response.