Money Can't Buy Me Love

The 2016 presidential contest will put the lie, but probably not the kibosh, to the case for campaign finance regulation. The contest’s results thus far—which, granted, is not very far—indicate what common sense says: money cannot protect candidates for whom citizens do not want to vote, nor are excessive sums necessary for those to whom the electorate is drawn. This is doubly true in an age where adequate means of communication are essentially free.

The same independent money on which rebel candidates like Eugene McCarthy once thrived is now sustaining the campaigns of several contenders, thus broadening the choices of voters. It simply cannot sustain them against voters’ will, as Rick Perry and Scott Walker know. Their fundraising topped $15 million and $26 million respectively, yet they were the first and second casualties of Donald Trump, who has “purchased” his slumping but still persistent lead by spending a paltry $1.4 million.

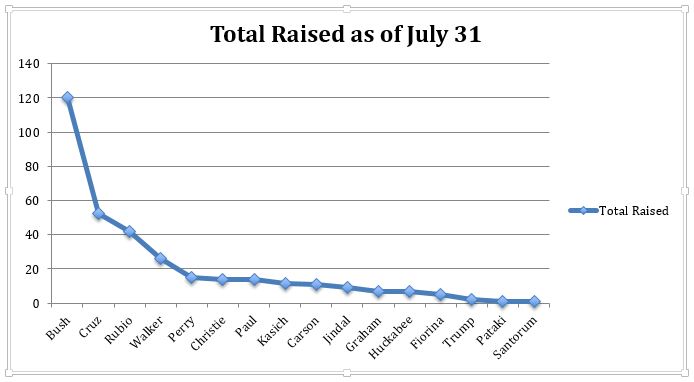

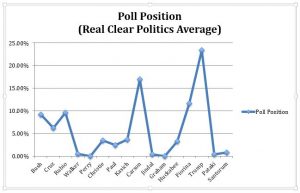

The dueling graphs of money raised and popularity registered are a study in statistical randomness. As of the July 31 FEC reporting period, the last available figures—which will be updated at the end of the quarter this week—Jeb Bush was sitting on $120 million. As of the last Real Clear Politics polling average, he was registering 9.2 percent support. Ben Carson had drawn $10.8 million and was trouncing Bush at 17 percent. Trump, who needs no one’s money, as he is wont to remind us, topped the field at 23.4 percent—less than his previous 35 percent, and probably on the way down to far less, but still an impressively stubborn lead whose erosion can hardly be attributed to fiscal anemia.

The only place where money could be said to align with results would be mediocrity, which is to say that candidates who have raised middling amounts of money—Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz—are achieving middling results. That holds except for those (Chris Christie, Rand Paul) who are raising middling sums and achieving pathetic results, thus proving that political analysis is complicated by the fact that voters think.

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, boasts a cash haul of $67.8 million but is losing to Bernie Sanders in New Hampshire. The reason—deep-insight alert—is a lack of enthusiasm for her candidacy. By contrast, voters do—into this, no deep insight is offered or perceived—feel the Bern, to whom, incidentally, the best thing that could happen is a plutocratic Super PAC.

To be sure, the candidates have not, for the most part, yet unleashed these millions, though Clinton had, as of July 31, torched an astonishing $18.7 million. And these GOP poll numbers, being national, do not account for the devilish details of Iowa and New Hampshire, where a ground game and therefore money will matter more.

Yet the poll numbers in those states are not dramatically different. And the incapacity of money to account for the macrosorting of candidates at the national level is revealing. The most important sorting events thus far have entailed no money and, in fact, have been filtered through the celestial prism of journalism: the televised debates.

The reason is not shocking to anyone with so much as an elementary-school understanding of American civics, which means very few elementary-school students in the era of Common Core, but I digress. The elemental understanding, which escapes hand-wringing journalists, is this: Votes win elections. Money does not. There is not a precinct in America—insert jokes here, but actual corruption is both criminal and rare—that sets ballot boxes aside and counts contributions instead.

Money buys the means of persuading votes. But it is only decisive if Americans are gullible in the aggregate, over time. Journalists and reformers who would never impute such credulity to themselves or their peers are only to happy to assume it in those they view as their lessers, such as Kansan altruists with whom, with the genuine curiosity of one inspecting a biological specimen, they want to know what the matter is.

This is a strange populist brew. Like many, it is made from elite hops. As such, it is ultimately a solvent not of plutocracy but of self-government, for the latter cannot survive as the reformers’ ideal if the voters are as gullible as the reformers’ caricature.

Since money only buys the means of persuading votes, taking money from minority factions in exchange for backing policies that violate the interests of the very public one needs the money to persuade is inherently irrational. A genuine bribe of that description would only be rational if—hypothetically and all—government did so many things that no one could reasonably be expected to take notice of them or, if someone did, he or she could not afford to spend the single vote everyone gets reacting to an instance of corruption on an ancillary issue.

Money thus helps only to the extent it achieves net persuasion, while it persuades only to the extent voters are receptive to the message candidates seek to convey. Mountains of it have not achieved liftoff for Jeb Bush because, fairly or not, he has been painted with establishment tar, and even molehills of expenditures have been unnecessary to propel The Donald to the front of the GOP pack.

In the Republican field, there will, of course, be considerable sorting out. In Madisonian fashion, passion will dissipate. Voters will eventually realize that the winner gets to be in charge. But money will not be responsible for it. At best the sorting will be overdetermined, and money may well follow whomever can pull it off.

To be sure, communication is hardly the only function of campaign finance. Ground games are immensely expensive. Once the sorting out occurs, money will be a necessary condition for pushing on. It should be. Raising adequate money to fund a campaign is a reasonable test of a candidate’s support and skill. There is no entitlement to success in politics. Candidates who cannot, in the current regulatory environment, attract adequate funds probably ought not be in the race. Those too sanctimonious to try are probably too self-righteous to govern.

In the last analysis, no candidate can plausibly emerge from the 2016 Presidential campaign complaining that he or she was unable adequately to communicate with voters. The constitutional objections to campaign regulation are, of course, adequate to its defeat. But the 2016 campaign is exposing its policy vacuities too.