Despite all appearances, the Democratic takeover of the House increases the odds of Trump’s reelection in 2020.

The Case for the Unitary Speaker

The debate over who will be the next Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives is really a debate about the structure of power in our political system. Members of the House’s Freedom Caucus argue that power has become too centralized and reforms must open up the legislative process to more members. They allege that the Speaker has become too powerful and that the House is being run as a top-down institution.

A short history of the office would be helpful to evaluate this claim. Upon examination, history tells us that we actually do not have a strong, but a weaker Speaker.

The Speaker played a minimal role in the first years of our history. With so few representatives, each bill could be debated and amended by the entire House. This model left a leadership void. As a result, the executive branch set the legislative agenda. Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, wrote reports, crafted proposals, and sent them over to be passed into law. President Thomas Jefferson actually drafted bills for Congress to enact.

Over time it became clear that without internal leadership Congress was more easily dominated by the President and the administration. It is no coincidence that every time the House stripped powers from its Speaker, power moved to the executive. Power moved back to Congress whenever the Speaker’s role was strengthened.

This process began in 1811 with the election of Henry Clay of Kentucky to the House of Representatives—and to the Speakership on his very first day serving in Congress—and continued throughout the 19th century. By 1900, the Speaker had accumulated massive influence, rooted in three powers: 1) the power to name the members and chairs of committees; 2) chairmanship of the Rules Committee, which controlled the order of legislation and rules of debate by issuing “special rules” to bring legislation to the top of the legislative calendar; and 3) the power to recognize members and therefore determine what business would be conducted and who could speak.

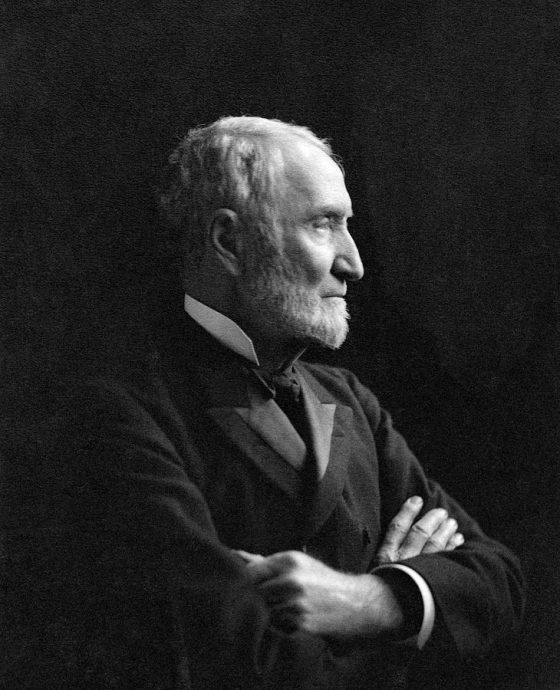

Thomas Reed (R-Maine), elected Speaker in 1889, was the most important figure in instituting these changes. Unless the party’s leaders can control the order of bills, the number of amendments, and the length of debate on the floor, Speaker Reed reasoned, the minority can prevent the majority from acting by exploiting the rules. As he argued, “The object of a parliamentary body is action, and not stoppage of action. Hence, if any member or set of members undertakes to oppose the orderly progress of business . . . it is the right of the majority to refuse to have those motions entertained.”

The “Reed Rules” of 1890 consolidated control of the House in the Speaker’s hands and established the concept of party responsibility, in which the party that wins a majority of the country gets to implement its legislative agenda through strong leaders who can control the business of the Congress. Party responsibility thus achieved two important objectives: 1) guarding Congress’s powers from executive usurpation, and 2) allowing the majority to implement its agenda.

This concept was short-lived because Progressive reformers revolted against the strong leadership of Joseph Cannon (R-IL), chosen as Speaker in 1903. Cannon was a strong conservative Speaker who used his powers to block Progressive legislation advanced by Theodore Roosevelt and Progressive Republicans in the House.

These insurgent Republicans and Democrats stripped the Speaker of his powers in a revolt in 1910. The Speaker lost his power to make committee assignments and was removed from the Rules Committee.

The consequences were massive. Power was radically decentralized in the House, allowing individual members to operate outside of their party’s agenda, and the ability to block legislation increased dramatically. (It also created many more access points for lobbyists and interest groups to influence legislation.) With a large legislature following so many different constituencies and interests, leadership had to come from somewhere. Administrative power and the President stepped in to fill the void of setting the agenda for the House.

The person who saw this problem most clearly was Newt Gingrich (R-GA), selected as Speaker following the 1994 elections that gave Republicans control of the House. Gingrich saw that Congress’s weak internal leadership facilitated the growth of government, and that the best way to reverse the growth of government was to reestablish some of the Speaker’s powers. By implementing the will of the majority, a strong Speaker simultaneously prevents small interest groups from tyrannizing over the majority and prevents unwanted expansion of the state.

In order to empower the Republican majority, Gingrich reasserted control over committee members and chairs and increased the Speaker’s representation on the Steering Committee, (which proposes committee assignments). These are the powers that the Freedom Caucus now seeks to strip from the Speaker.

Conservatives are rightly concerned about a government that is unresponsive to the will of the people, where narrow interests prevail over the long-term good of the country. But history shows that the parties have been the best mechanisms for limiting government, checking the executive, and implementing the will of the majority. A weaker Speaker achieves none of these important goals.