When judging the past, recall we were not born yesterday, we come from different places; we are in a bad as well as a good sense a “nation of immigrants."

Film the Legend

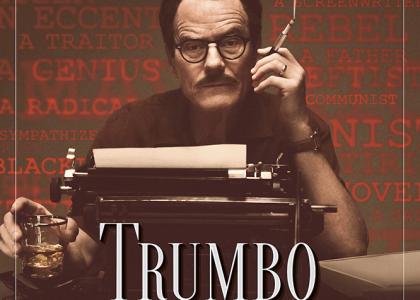

On publicity junkets for Trumbo, star Bryan Cranston has repeated the line, “Everyone has the right to be wrong.” Cranston claims this quote came from Dalton Trumbo himself, and shows that the blacklisted screenwriter supported and defended everyone’s right to free speech.

The real Trumbo didn’t. The movie is frank about his membership in the American Communist Party, but its makers (director Jay Roach, screenwriter John McNamara) give us not a hint of what that entailed, or how roundly contradicted is Trumbo-the-free-speech-avatar by Trumbo the actual person.

Trumbo celebrates the screenwriter’s battle against the blacklist. There is much to be said for his go-it-alone fight against the Hollywood producers, but the image of him as a New Deal liberal hero defending civil liberties against homegrown fascists crumbles when you look into what he said and did in the 1940s and 50s.

His daughter Nikola has said that being a communist in that period had “nothing to do with Russia” but was instead about the “rights of workers.” If so, Trumbo spent a great deal of “wasted” time defending Joseph Stalin. It is easy to confirm his zigs and zags in accord with the policy changes out of Moscow throughout much of his adult life.

When Stalin allied with Hitler in 1939, and announced that comrades should not support Great Britain’s military response to the Third Reich because it was an “imperialist war,” Trumbo followed suit. He wrote many vociferous attacks on the British during the nearly two years of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, despite that they were almost alone in fighting Hitler. His novel Johnny Got His Gun (1939) carried the same pacifist message, for the same reason—a fact that those who celebrate it rarely discuss.

To help the non-interventionist cause, Trumbo even defended the Third Reich. In response to Hitler’s crackdown on France, the famous civil libertarian disputed reports of Nazi brutality coming out of France, declaring that “To the vanquished all conquerors are inhuman.”

When the socialist motherland was invaded two years later, Trumbo suddenly and with equal passion switched to supporting the Allies’ war against Hitler. When asked how he could reconcile the pacifistic theme of Johnny Got His Gun with his newfound bellicosity, Trumbo explained that the quadriplegic, blind, and deaf character he created would have supported the Progressive nature of the war.

The convolutions are breathtaking. The sudden ex-pacifist now found it necessary to denounce pacifists as fascists because they wouldn’t get into the effort to defeat the fascists. And an entity he had just gotten done lambasting as an American Gestapo, the FBI, was now worth helping. The famous civil libertarian encouraged the Bureau to arrest those who spoke out against the war (which, to be fair, did include some homegrown fascists).

After the war’s end, Trumbo’s thinking took a not very surprising turn back to peace as promoted by the Russians. He portrayed the Soviet regime in the manner it presented to the world: as a Progressive country that liberals could easily support. As Stalin swallowed up Bulgaria, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, and repressed countries such as Poland, Trumbo amazingly penned a 1946 article asserting that the Soviet Union “had no colonies.” In 1949, a year after being blacklisted, he doubled down, declaring the Soviet Union had no anti-Semitism because it was forbidden by the Soviet constitution.

Uncle Joe needed to be protected not only from the supposed fascists who ran the U.S. government but by rival revolutionaries: the Trotskyists. Trumbo, the famous civil libertarian, bragged of enforcing his own blacklist by keeping such “reactionary and untrue” works as Leon Trotsky’s “so-called biography of Stalin” from making it to the big screen.

The FBI, by the way, was bad again. He denounced it during the Cold War as a “hateful shadow preying on the citizenry.” Meanwhile, as late as 1956, he was still asserting Stalin to be “one of the democratic leaders of the world.”

If the arrogant Trumbo felt a sense of entitlement, so did many of his comrades, for the World War II period was the high tide of communist influence in the film industry. Not only were those like Trumbo highly paid for cranking out screenplays (into which they tried, with only limited success, to insert their pro-Soviet and pro-collectivist point of view), they had a power that reached beyond the industry. John Howard Lawson, the autocratic head of the Hollywood Communist Party, penned the 1942 California Democratic State platform. Trumbo himself wrote speeches for Secretary of State Edward Stettinius.

At the point when Soviet crimes became hardest to deny, the 1956 speech by Nikita Khrushchev admitting that Stalin had killed thousands of innocent people during the Purge Trials of the 1930s, Trumbo again had a characteristically arrogant response. He wrote to a communist friend that he was “not surprised,” having read all the notable anticommunist writers like Arthur Koestler and Ignacio Silone—even Leon Trotsky! So he knew about the murderous policies of Stalin all the while that he publicly defended the dictator? Yes, if that statement is to be believed. (Another possibility is that he just said that in order not to look like a dupe, which would have offended his dignity greatly.)

He enjoyed his position as editor of the prestigious movie-industry journal, The Screenwriter, and it cut no ice with him at all when one anticommunist writer pressed him to publish, in the interest of freedom of expression, an article that Trumbo didn’t agree with. Trumbo, as he rejected the man’s submission, informed him that freedom of expression wasn’t an inalienable right, in fact was downright fascistic and had led to the Holocaust.

Trumbo sidesteps such compromising matters. Clearly they would jeopardize the portrayal of Trumbo as civil libertarian extraordinare. The most criticism the movie allows in is that 1) Trumbo was a limousine communist who craved all the creature comforts of capitalism, and 2) he behaved autocratically toward his wife and children. The movie opts for a breezy, light approach at times (director Roach also made Meet the Parents in 2000 and the Austin Powers movies). But its “screwball comedy” tone halts when it comes to lauding Trumbo as a civil libertarian.

McNamara has said that he did “an enormous amount of research” to write the script, but that his chief source material was Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography of Dalton Trumbo. The Cook biography has been rereleased in conjunction with the film, and in fact Cook is listed as cowriter in the film credits. What is notable about this 1977 work is that it is a kind of time-capsule document of the attempted rehabilitation of Reds in the context of an anticommunism that was being blamed for the carnage of Vietnam.

In the era of the antiwar movement and Watergate, the countercultural Left was in the ascendant, and one sign that they were feeling their oats was their eagerness to promote the rehabilitation of the Hollywood communists of old. For Cook, and many other journalists, biographers, screenwriters, and novelists from E.L. Doctorow to Arthur Laurents (whose novel was the basis for the Robert Redford-Barbara Streisand pro-Popular Front movie, The Way We Were {1973}), the robotic Stalinoids among their elders were now airbrushed into heroic civil libertarians.

And now the time capsule has been removed from its cask and given the imprimatur of accuracy, with the movie following the biography in retaining in every detail Trumbo’s claims about himself as he sat before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Early in the biography, the reader is helpfully alerted to a certain bias. Cook calls himself an “advocate” for his subject. Indeed he bases his account on interviews only with Trumbo’s admirers, such as his wife, his comrades in the Party, and fellow travelers including Cary McWilliams, editor of the Nation. No adversaries are heard from.

Ronald Reagan, for example, would have been instructive. Reagan went head to head with Trumbo and the other leading Hollywood Reds during the fight for communist control of the Screen Actors Guild in 1946. He recalled Trumbo’s defending the Soviet constitution as more democratic than the American one.

Cook tiptoes so cautiously around these aspects of his subject that Trumbo himself has to bring up the question of his Party membership. The biographer swallows whole the screenwriter’s explanation for joining in 1943—that he had long been allied with the Reds ideologically but now foresaw trouble ahead for the Party from anticommunists. Supposedly he signed on as a way of supporting, in their time of need, those alongside whom he had fought the good fight.

It would be no defense to say the compromising material alluded to above was not available in 1977. Trumbo’s defenses of Stalin, and (as unearthed by writer Allan Ryskind) of North Korea during the Korean War—along with the chilling statements about who, in Trumbo’s judgment, deserved to have his civil liberties respected and who didn’t, have been available in Trumbo’s papers donated to the University of Wisconsin repository since the 1960s.

Indeed one gets a sense throughout the film that McNamara knows Trumbo’s politics were hardly democratic. Other characters do call him a “swimming pool Stalinist.” But most such comments come from the hardline Right, whose representatives in the film are presented as the destroyers of civil liberties. McNamara has Trumbo land comfortably (and falsely) in the sensible center by ranging horrible people to his right, while contrasting him, on the other end of the spectrum, with Arlen Hird, a more hardline comrade played by Louis C.K. In response to Hird’s wish that everyone earn the same salary, McNamara has Trumbo reply urbanely that that would make for “a dull world.”

McNamara does allow that Trumbo was one to dismiss political arguments with frothy spin. Criticized by Hird for “talking like a radical while living like a rich guy,” Trumbo hastily improvises by reasoning that “a radical can fight with the purity of Jesus, but a rich man wins with the subtlety of Satan.” “Please shut up,” replies his comrade.

It’s a pity that this is the only moment in the film when a bullshit detector is applied to Trumbo. For, if one accepts that he did know what was really going on in the Soviet Union, he peddled his own brand of it albeit in a witty manner. The rest of Trumbo lets its hero present to a credulous world, as if it were real, the hollow image of a supposed defender of everyone’s right to be wrong.