Dostoevsky asserted the internal reality of the spirit against the external illusions of behavioral science.

Lawyers Should Read Dostoevsky

Moments of disorienting despair, or of painful honesty, can strip away our comforting self-conceit and force us to recognize what a disquietingly thin barrier it is that separates the decency of civilized life from the brutality of barbarism. If the barrier is thin—and there is too much evidence to deny it—do we have the strength, character, and means to maintain, and thereby meet the challenge of defending, that decency?

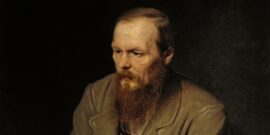

Continuing affirmation of the hard-won gains of a constitutional liberal order—above all, the achievement of a secure rule of law—is what makes possible our muddling through daily life with the freedom to act with a semblance of moral rectitude and compassion toward our fellow human beings. Such affirmation was absent in the world of Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881). Hence the Dostoevskyian questions: Do we face life with an open hopefulness or a restricting, fearful futility? Are we able to live with compassion and the freedom it requires? Or do we live in a senseless universe that, as such, knows no, or at least does not compel, humane constraints on our choices?

Recognition of the precariousness of civilized life is a major reason that Dostoevsky’s fiction—The Gambler (1866), The Idiot (1869), and, of course, The Possessed (also known as Demons)(1872)—exerts such a hold on our attention. As do his famous characters—the likes of Golyadkin in The Double (1846), Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment (1866), Ivan and Mitya in The Brothers Karamazov (1880), and Goryanchikov in The House of the Dead (1861-2).

A reasonable objection can be raised concerning our psychological precariousness arising from the ever-present possibility of descent into barbarism: Such a recognition is wont to push a possibility to the limits (what in another context is sometimes characterized as the “politics of exception,” as in Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology). Doesn’t the Dostoevskyian kind of awareness tend to minimize, if not dismiss, the decency of everyday relations, including our propensity to truck, barter, and trade, and the religious, legal, and political traditions upon which those relations are based and sustained?

That Dostoevsky in his fiction may have pushed the limits of this possibility is clear enough; one need only recall Raskolnikov. Perhaps we can understand why when we remember that, in 1849, at the age of 27, Dostoevsky was arrested and sentenced to death for being a member of the utopian socialist Petrashevsky Circle, only to be spared execution just a moment before the firing squad discharged its life-extinguishing shots. (His sentence had been commuted to four years of hard labor and exile in Siberia.) The author’s experience with the Petrashevsky Circle provided the basis for his novel The Possessed, which exposed the manipulative cruelty of the revolutionary intellectuals’ desire for power. His imprisonment and exile were surely the basis for creating Alexander Petrovich Goryanchikov, who narrates The House of the Dead.

It seems obvious to point out, in any case, that Dostoevsky’s preoccupation with the thin line between civilized life and barbarism, as expressed by the anguished choices that his characters make, was not juridical. He was not explicitly concerned with the rule of law or, for example, a constitutional separation of power. He was not concerned with the traditions that sustain law, private property, or institutional arrangements that make contracts, corporations, and individual rights possible. Dostoevsky’s characters are developed as if they stood naked in the world: if not uncertain of, at least poorly prepared to maintain, the distinction between right and wrong, as if unencumbered by any life-sustaining traditions except for that of Russian Orthodoxy.

This is not to gainsay that freedom is central to his novels and short stories, for it surely is. Facing their fateful and terrifying choices, his characters labor under the burdens of freedom. However, it is not a Western, political, and juridical freedom; it is, above all, a spiritual freedom, specifically, the ability to choose properly that is seemingly only achieved through salvific suffering which alone makes possible decency and compassion. Here, too, his portrayal of this achieved ability is pushed to its limits.

Perhaps it can be said that the author’s concern was with justice and not law; and that it is in pursuit of justice that his characters run up against the Dostoevskyian extremes. In any case, Amy D. Ronner’s interesting and worthwhile new book seeks to examine “how law, in its broadest sense, operates in Dostoevsky’s writings.” Each of its chapters takes up a current problem of law that also appears in Dostoevsky’s novels; and so each chapter has extended discussions of recent, American court cases with lengthy, often illuminating analyses of apparently parallel problems as they occur in Dostoevsky’s fiction.

Chapter Two of Dostoevsky and the Law competently discusses a number of court cases concerning the legal doctrine of mental capacity—specifically, its bearing on testamentary freedom, that is, the requirement that a testator be of sound mind. Ronner uses Dostoevsky’s novel The Double as a point of reference for her discussion of the doctrine of mental capacity precisely because this novel raises the possibility that “what its readers (hence, lawyers and judges) think they see or know, they might not see or know.” Thus, we might not know who Golyadkin really was: Golyadkin, the double, or even if there actually was a double, presumably presenting a parallel to American court cases involving the legal quandary of determining mental capacity and delusion.

Chapter Three is concerned with the legal issues surrounding confessions, specifically, the problem of coerced and false confessions. As a consequence, this chapter discusses court cases involving the Due Process Clause, the Miranda decision, and the U.S. Constitution’s Sixth Amendment, all of which are intended to minimize the possibility of false confession by making more likely that confessions are the product of free and rational choices. In seeking to illuminate current legal problems, Ronner draws upon, from Dostoevsky’s work, the confession of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, and Mitya and Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov to explore the phenomenon of confession, including, above all, the compulsion to confess falsely.

Chapter Four analyzes the extent to which the U.S. Supreme Court has, in its post-Miranda decisions, undermined the previous protections of the Due Process Clause and Miranda of persons against coercion (227-262). Ronner argues that the Maryland v. Shatzer (2010) and Howes v. Fields (2012) decisions, along with “the plethora of Miranda exceptions[,] have inaugurated an area of advancing, or at least tolerating, interrogation methods that coerce and even torture.” The result of this “progressive dismemberment of Miranda” is, according to Ronner, to recreate the kind of conditions that defined Goryanchikov’s “dead-like” existence in Omsk prison, as described in The House of the Dead. The “unsettling likeness between Dostoevsky’s Omsk fortress and our own prisons,” so Ronner argues, “transmit[s] a message which imprisons, detriments, and flogs us all.”

It is a commonplace that law is not the same thing as (entails a different understandings of) justice. Ronner seems to have lost sight of this distinction in what is otherwise a stimulating book. Thus, she is surely right when she perceptively observes that, for Dostoevsky,

the New Testament image of Christ, along with the ideal of compassion and brotherly love, must be integral not only to our understanding of what it means to be a free moral agent, but also to our notions of innocence, guilt, and forgiveness.

However, in the context of this justice, confession is intricately bound up with salvation, not determination of legal fact; and innocence, guilt, and forgiveness take on contours of a justice that one does not and should not expect from law.

Furthermore, while it is certainly the case that mental capacity, confession, and coercion appear in Dostoevsky’s novels as legal problems, their presence is overwhelmingly in the service of exploring the psychological fragility of humanity as it navigates between civilized decency and barbarism. Thus, there is an artificiality to Ronner’s linkage of, for example, the legal doctrine of mental capacity and testamentary freedom to the plot of The Double, or the Due Process Clause and Miranda to the confessions in Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov, or the post-Miranda decisions to The House of the Dead. The problem, for example, of a testamentum inofficiosum, presumably indicating mental incapacity, is longstanding in the history of law, with various attempts, right or wrong, to constrain freedom of testation when confronted by the importance of familial relations, for example, as in Roman and Canon Law.

So much for the weaknesses of this book. Still it suggests to us, and eloquently, that our lawyers ought to read Dostoevsky. Doing so would enrich their imaginative engagement with today’s legal problems; it would lift their gaze to the perennial truths, and the roughly parallel dilemmas, that appear in the great Russian’s works. Herein lies the attraction of Ronner’s engaging and original study.