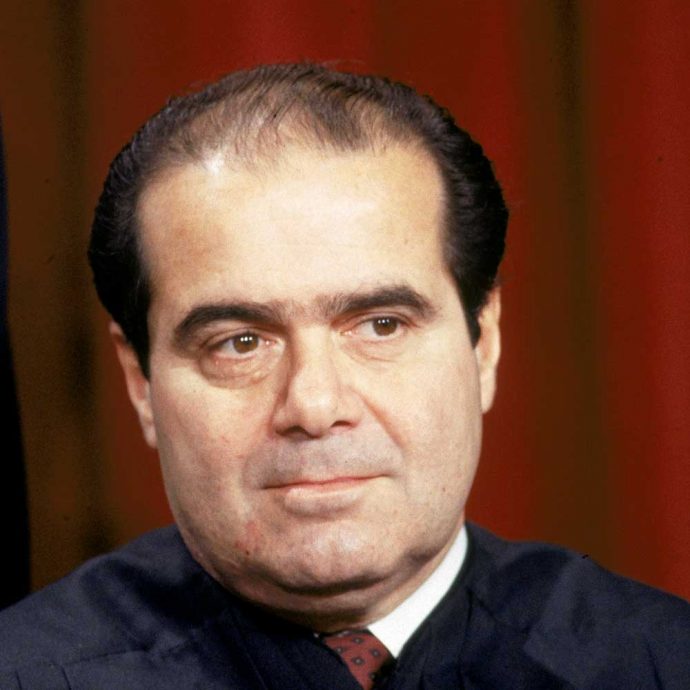

Antonin Scalia--A Giant of Jurisprudence

Justice Scalia is one of the few jurists who vindicate Carlyle’s great man theory of history. Because he brought three large and different talents to the Court, he changed the course of its jurisprudence. He had the intellect to fashion theories of interpretation, the pen to make them widely known, and the ebullience to make it all seem fun.

More than any other individual, Justice Scalia was the person responsible for the turn to both originalism in constitutional law and textualism in statutory interpretation on the Court and in the legal world more generally. Indeed, it was Scalia who made a crucial move in modern originalist theory. While a variety of scholars had argued that the Constitution should be interpreted according to the intent of the Framers, original intent originalism had some disabling flaws, the most important of which it is impossible often to find a unitary intent in a multimember deliberative body. Scalia championed a theory of original meaning that made the Constitution depend not on the intent of the Framers but on the publicly available meaning of its provisions.

And he then skillfully applied this theory in case after the case on the Court. And he did so in way that gave the theory credibility, because in a variety of cases, particularly relating to criminal defendants, he came to results that were at odds with the political preferences of a conservative Republican. To be worthy of the name, any jurisprudence must not be simply politics by another name, and he shamed many of his opponents by showing that his was not.

But his work would have been mostly of interest to academics had he not been such a brilliant writer. With pungent, pellucid prose he was able to reach over the heads of the elites to the American people. And this was a crucial skill, because the bar and academia was dominated not only by people on the left but by legal realists of one kind or another—those who disparaged the constraining power of the language. His clever words were thus in service of the word itself.

Opponents decried his sharp and energetic style as shrill and bombastic, but Scalia knew well that a modulated moderation would have made no dent in the complacent prejudices of the legal elite, nor would it have attracted any attention in the world. He was so incisive that he persuaded many law students despite their professors and their prior beliefs. And he did have another weapon to deploy to prevent his opponents from representing him as angry crank—his personal charm and wit. No other justice could inspire both a play and an opera. He was such a large and cheerful character that that he disarmed his critics and made many seem themselves shrill and humorless.

His death leaves a huge void, and given the discontents in the nation, I tremble when I consider the future of the Court. But his work is done and to me the verdict is clear: he did more than any justice in the last hundred years to set constitutional law on a sound path.