Lincoln and the Other Washington

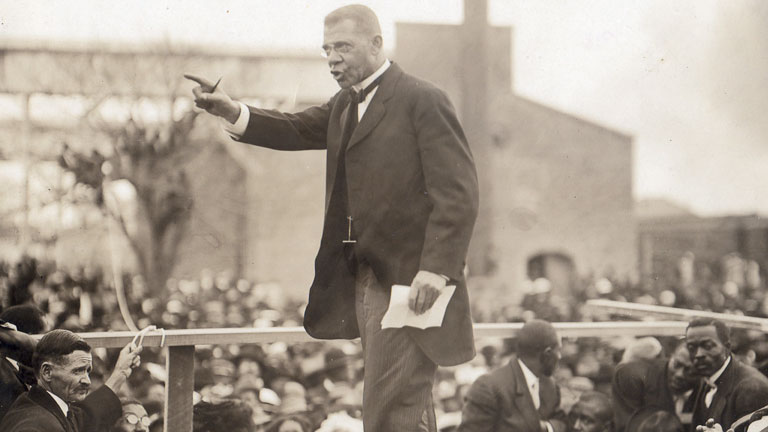

On the centennial of Lincoln’s birth, February 12, 1909, Booker T. Washington delivered an important speech before the Republican Club of New York City. His “Address on Abraham Lincoln” deserves to be better known. Not only does it provide an astute assessment of the Great Emancipator’s virtues and legacy, but it demonstrates the ability of a talented statesman to deploy the memory of Lincoln to meet pressing needs of the moment. Washington’s address is no purely celebratory endeavor, much less an historiographic endeavor—any more than was Frederick Douglass’ acclaimed “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln,” delivered three decades earlier on the 11th anniversary of the assassination.

Because he was scheduled to speak in New York, Washington had to decline an invitation to speak at the Springfield ceremonies. In the letter declining the invitation, Washington indicates that he would have preferred Lincoln’s Illinois home as his venue, not only because of its nostalgic associations but because of its present notoriety: it had been the site of a terrorizing race riot just the previous summer.[2] Two days of anti-black mob rule, complete with lynchings, had been followed by weeks of sporadic attacks against black homes and businesses. Washington’s public letter of regret, like Lincoln’s “Lyceum Address” of 1838, examined the causes behind the growing national threat of lawlessness and, among other stratagems, appealed to civic piety in response. As Lincoln had summoned the spirit of George Washington, Washington’s namesake, Booker T., invoked the memory of Lincoln.

It’s worth noting that the Springfield riots also catalyzed the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The integrated group that organized the “Lincoln Conference on the Negro Question” declared the 1909 Lincoln centenary to be the official founding date of the NAACP—another attempt, though different in tactics and tone, to muster Lincoln on the side of racial progress.

Today, we tend to feel at ease with the language of protest; like good Boston radicals, we have grown accustomed to what Washington derided as “indignation meetings at Faneuil Hall.” As a result, Washington’s seemingly more conciliatory voice triggers our suspicion. The prevailing impression of Washington as “accommodationist” is, however, a misimpression. While not fierce and fiery like so many of his predecessors and successors, Washington may well be the bolder critic of American society, with more profound reforms in view.

It’s true that Washington’s deferential modesty is what strikes one first. He begins his “Address” by announcing that he is “not fitted by ancestry or training to be your teacher tonight.” Quickly though, he also indicates that he possesses “knowledge of Abraham Lincoln”—firsthand knowledge at that. Stressing his slave origins, he tells the story of his mother’s wartime prayers for Lincoln’s success. Although Lincoln is credited with turning “a piece of property” into “a free American citizen,” Lincoln is curiously humbled also, since he is presented as “the answer to that prayer.” He was “an instrument used by Providence.” Washington situates his celebration of Lincoln within the wider context of a dialogue with God initiated by freedom-seeking slaves.

Thus, an attentive listener hears not only expressions of modesty but, in counterpoint, a well-grounded claim to knowledge, an illustration of black agency in the slave mother, and an absolute conviction of slavery’s injustice. Moreover, these competing notes are all subordinated to the dominant strain of religious or metaphysical humility (Washington thought of himself, as he did Lincoln, as a servant of higher purposes—this is the ultimate ground of his modesty vis-à-vis his fellow man).

In considering how an audience might react to Washington’s words, especially his seeming self-deprecation, it is important to remember that the man standing before them had reached the pinnacle of human accomplishment, and the whole world knew it. The juxtaposition between his beginnings—“wrapped in a bundle of rags on the dirt floor of our slave cabin”—and his current power and fame, though decorously unmentioned by him, spoke as eloquently as any words could.

After this very brief opening, Washington’s “Address on Abraham Lincoln” unfolds in two roughly equal parts, one tracing the consequences of the Emancipation Proclamation, the other exploring Lincoln’s virtues.[1] These parts follow a pattern, as the respective themes are discussed first with application to American blacks, then American whites, and finally people around the globe.

Washington sets forth a unique interpretation of the significance of the Emancipation Proclamation. While grateful for “freedom of body,” he argues that the real effect of slavery’s abolition is spiritual. This is true for blacks—who can now act on the inner resolve “to perfect themselves in strong, robust character”—but just as profoundly is it true for whites. Washington informs his white audience that “the same pen that gave freedom to four millions of African slaves at the same time struck the shackles from the souls of twenty-seven millions of Americans of another color.”

The delicate phraseology—“Americans of another color”—conceals a bold move. Implicit in his formulation is that “African slaves” are now Americans; indeed, they are Americans of color as compared to whom whites are “Americans of another color.” Who would have suspected that the critical race theorists who aim to “decenter whiteness” owe a debt to Booker T.—whom they denounce as an “Uncle Tom” if they bother to acknowledge him at all?

Just as important as Washington’s assertion of equal and multiracial Americanness is his insistence on the paradoxical truth that the oppressors were all along the real slaves. He explains the inversion with this simple image: “so often the keeper is on the inside of the prison bars and the prisoner on the outside.” Traditionally, we credit Lincoln with having performed two great tasks: saving the Union (his presidential duty toward the citizenry) and ending slavery (a boon for blacks that was necessary to fulfill his primary duty). However, Washington reads the Emancipation Proclamation as the “symbol” of a more momentous transfiguration. In abolishing slavery, Lincoln “freed men’s souls from spiritual bondage; he freed them to mutual helpfulness.”

While Washington is a great defender of obedience to law, for him, the state of one’s heart is always more fundamental than the exterior provisions of law:

In any country, regardless of what its laws say, wherever people act upon the idea that the disadvantage of one man is the good of another, there slavery exists. Wherever in any country the whole people feel that the happiness of all is dependent upon the happiness of the weakest, there freedom exists.

The conclusion is inescapable: to the extent that whites now choose to continue the politics of “sectional or racial hatred,” they “warp and narrow” their own souls, and imperil the nation’s liberty.

It’s a difficult thing to correct others, and likely to be regarded as insufferable presumption when those you are targeting regard themselves, wrongfully, as by nature superior and when law and custom then enshrine that status (our contemporary shorthand for this is “white privilege”). Washington responds to this rhetorical dilemma by doubling down on the personal element. Because this is a spiritual matter before it ever gets expressed politically, Washington turns to a consideration of Lincoln’s virtues: Lincoln the man rather than Lincoln the president is our best guide.

In this second half of the speech, Washington again addresses blacks first. He highlights Lincoln’s virtues of patience and courage, meaning especially “moral courage.” He recommends emulating Lincoln who struggled in the face of adversity, overcoming “abject poverty and ignorance” to rise “to a position of high usefulness and power.” Without scorning the “bequest” of freedom, Washington makes very clear that “in the broadest and highest sense,” freedom must be an individual “conquest.” The “dogged determination” of Lincoln’s life “points the road for my people to follow.”

When he turns to recommending Lincoln as a model for whites as well, Washington pivots from the individual aspect of Lincoln’s striving to the interpersonal aspect of how Lincoln treated others along the way. Secure in himself, Lincoln was “just and kind” toward “the lowly of all races.” In the first “white” section of the speech, Washington put forth a principled argument challenging white supremacy, couched, in part, as an appeal to white self-interest. (Stressing the harm that oppression does to the oppressors, he remarks: “One man cannot hold another man down in the ditch without remaining down in the ditch with him.”) Now, he makes a sophisticated appeal to that very belief in white superiority to redirect whites toward more charitable behavior.

Perhaps surprisingly, he aligns Lincoln on the side of “white pride.” Lincoln, himself “a Southern man by birth,” was yet “one of those white men, of whom there is a large and growing class, who resented the idea that in order to assert and maintain the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race it was necessary that another group of humanity should be kept in ignorance.” Whites should be big enough to act big.

This is flattery with a transformative purpose. Washington throws the taunt of cowardice in the face of those who seek to deny new possibilities to blacks: “it requires no courage for a strong man to kick a weak one down.” Then, he goes even further, audaciously extending his pity to these fearful men who pursue a Trump-ed up greatness through belittling others.

Herein lies the true, and largely unappreciated genius of the speech. Because he understands the intransigence of race pride, Washington does not, for the most part, confront it directly; instead, he contrives ways to disarm and reconfigure it. Through his psychologically acute rhetoric, he shows white Americans that their proper pride lies in dedication to “the Lincoln spirit of freedom and fair play.”

Inveigling whites to make room for black advancement and inspiring blacks to struggle and triumph, Washington by the end of the speech is able to address his audience as “brothers all.” What a conjoined nation is invited to do is laid out most clearly in the very middle of the speech where Washington sketches a picture of the place that Lincoln reached:

He climbed up out of the valley, where his vision was narrowed and weakened by the fog and miasma, onto the mountain top, where in a pure and unclouded atmosphere he could see the truth which enabled him to rate all men at their true worth. Growing out of this anniversary season and atmosphere, may there crystallize a resolve throughout the nation that on such a mountain the American people will strive to live.

This February, as we celebrate Lincoln’s birthday, Washington’s birthday, and Black History Month, we should study Booker T. Washington’s “Address on Abraham Lincoln” in preparation for an honest assessment of where we are today on that difficult ascent, collectively and individually. How many of us, by Washington’s mode of reckoning, are still slaves?

[1] For more analysis of the speech and its careful construction, see Diana J. Schaub, “From Statesman to Secular Saint: Booker T. Washington on Abraham Lincoln,” in Natural Right and Political Philosophy: Essays in Honor of Catherine Zuckert and Michael Zuckert, edited by Ann Ward and Lee Ward (University of Notre Dame Press, 2013), and my forthcoming essay on Washington in the Makers of American Political Thought series from the Heritage Foundation.