Do Judicial Deference Doctrines Actually Matter?

A central principle of modern administrative law is that federal agencies—not the courts—are the primary interpreters of ambiguous federal statutes that Congress has charged the agencies to administer. The Supreme Court crystallized this deference doctrine in its 1984 Chevron decision, though some variation had existed since the 1940s (and maybe even longer, or perhaps not). In 2005, Justice Thomas framed Chevron’s practical significance:

If a statute is ambiguous, and if the implementing agency’s construction is reasonable, Chevron requires a federal court to accept the agency’s construction of the statute, even if the agency’s reading differs from what the court believes is the best statutory interpretation.

That opinion, National Cable and Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services, upheld and expanded the doctrine of Chevron deference. But in recent years Justice Thomas has led the way in expressing skepticism about it.

He expressed serious constitutional concerns last year, in his concurrence in Michigan v. EPA. They were twofold: First, that Chevron deference impinges on the judiciary’s authority under Article III of the U.S. Constitution by giving agencies, rather than courts, primary interpretive authority over certain federal laws. Second, that Chevron deference raises constitutional nondelegation concerns under Article I. It does so, Thomas argued, by allowing “a body other than Congress to perform a function that requires an exercise of the legislative power.”

This summer two prominent federal court of appeals judges have joined the call to rethink Chevron deference. In a 23-page concurring opinion in Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Burch, Tenth Circuit Judge Neil Gorsuch advances a full-scale and colorful attack on the doctrine. He begins:

The fact is Chevron and Brand X permit executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power and concentrate federal power in a way that seems more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers’ design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth.

Similarly, in the pages of the Harvard Law Review, D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh argues (at 2154) that we should fix statutory interpretation by substantially cutting back on Chevron deference.

Perhaps encouraged by these statements, the U.S. House of Representatives last month passed the Separation of Powers Restoration Act, with the support of 239 Republican members and one Democratic member (Representative Collin Peterson of Minnesota). If enacted, the legislation would attempt to eliminate Chevron (and Auer) deference by amending the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 to instruct courts to “decide de novo all relevant questions of law, including the interpretation of constitutional and statutory provisions, and rules made by agencies.”

As I’ve explained, this legislation is unlikely to become law anytime soon. Nor is it likely that the Supreme Court will overturn Chevron deference, especially after Justice Scalia’s passing. Elsewhere I have addressed whether the Court should get rid of Chevron deference, and I’ve explored what the Supreme Court is more likely to do now to narrow Chevron’s scope. Numerous other scholars have offered varied opinions on the legislation, as well as on judicial attempts to narrow or eliminate Chevron deference.

Here, I’d like to shed some empirical light on one core question in the debate: Do judicial deference doctrines actually matter?

In other words, does Chevron deference actually do any work now in constraining courts and giving agencies more flexibility? The usual evidence adduced by the doubters centers on a seminal empirical study by Bill Eskridge and Lauren Baer of deference doctrines at the Supreme Court, in which they found that the Court has applied the doctrines inconsistently over the years.

To answer this question, however, it is a mistake to focus myopically on the Supreme Court to conclude that deference doctrines do not matter. (To be sure, that’s not what Eskridge and Baer were attempting to show.)

First, as I have explored empirically, Chevron deference sure seems to matter to the federal agency officials who draft regulations. The 128 rule-drafters surveyed in my prior study think about Chevron often when interpreting statutes and drafting rules. They also think about subsequent judicial review, and believe the rule is more likely to survive judicial review under Chevron than under the less-deferential Skidmore standard or de novo review. To a somewhat lesser extent, they also indicated that their agency is more aggressive in its interpretive efforts if it believes the reviewing court will apply Chevron deference (as opposed to Skidmore deference or de novo review).

Second, and perhaps more importantly, when assessing the impact of deference doctrines on judicial behavior, the federal courts of appeals are the better focus. After all, these circuit courts review the vast majority of statutory interpretations by agencies, and they do so knowing that further review in the Supreme Court is possible. Over the last three years, Kent Barnett and I have been coding every published circuit court decision from 2003 through 2013 that refers to Chevron deference—for a total of more than 1,300 decisions (and more than 1,500 total agency statutory interpretations under review). We report our findings in a new article, entitled Chevron in the Circuit Courts, which will be published in the Michigan Law Review next year.

I tweeted out a string of figures that summarize many of the key findings, and there are so many intriguing findings in this article concerning the scope of Chevron generally as well as differences by agency, agency procedure used, circuit, and subject matter. We also created rankings by agency, circuit, and subject matter. Those interested can check out the full draft paper here.

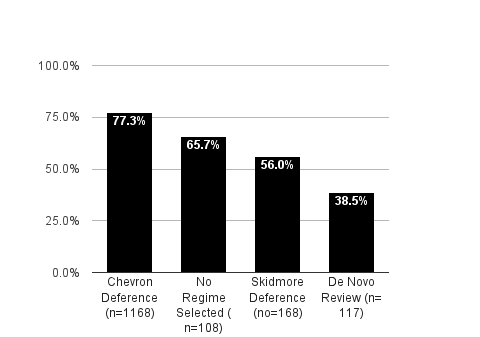

My purpose in the present, brief post is to zero in on one finding regarding the effect of Chevron deference in the circuit courts: There is a difference of nearly 25 percentage points in agency-win rates when judges decide to apply the Chevron deference framework, as compared to when they do not. (That is to say, at least in the cases reviewed, where Chevron was referenced in the published opinion.)

Figure 1 from the paper, reproduced below, breaks down the agency-win rates by deference standard applied.

Of course, one should be careful not to read too much into these findings, as there are also great differences in agency-win rates by agency, circuit court, and subject matter (and to a lesser degree the type of agency procedure used to create the interpretation). Similarly, there are methodological limitations inherent in this study, as is typical with any coding project, that should counsel caution.

That said, even these raw-number findings make it hard to argue that Chevron deference does not matter in the circuit courts. Whether or not Chevron deference should be shelved is subject to considerable debate—a debate that will no doubt continue for years. But the findings of our empirical study of Chevron in the circuit courts should put to rest the argument that deference doctrines do not matter.