Abandoning politics permanently in the face of conflict precludes us from using persuasion, negotiation, and compromise to resolve our disagreements.

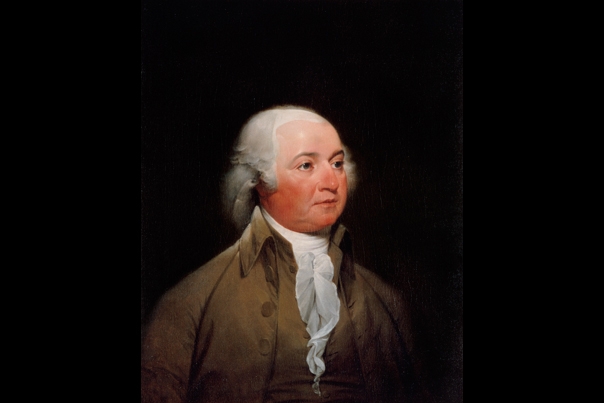

John Adams' Rules for Dealing with American Oligarchy

The verdict of history can be hard to overturn, even when patently unjust. Luke Mayville, postdoctoral fellow at the Center for American Studies at Columbia University, is a young scholar pursuing his own version of the Innocence Project. The beneficiary of his researches is John Adams, who despite his revolutionary bona fides and his manifold services to the new nation, was tagged a “monocrat” and a reactionary apologist for aristocracy by Thomas Jefferson and his partisans. Mayville’s fine first book, John Adams and the Fear of American Oligarchy, almost completely clears Adams of these old, but remarkably persistent, anti-democratic charges. Through a close reading of Adams’ major works of political theory and his late-in-life correspondence with his frenemy Jefferson, Mayville shows Adams to have been deeply worried about the power of privilege. By a twist of fate, an obsession with the oligarchic threat to popular government led to diagnosis being misconstrued as defense.

Mayville’s Adams, though he borrowed heavily from the Scottish moralists, especially Adam Smith, was a subtle and original thinker who applied Smithian psychological insights in a unique way to political life. What Adams discovered were the psychic foundations of oligarchic dominance. The wealthy get their way politically not because they buy influence (although, of course, they do sometimes do that), but because the very possession of wealth evokes the sympathy and admiration of ordinary folks, who tend to associate wealth with happiness.

To put this in terms of another activity that has two modes: wealth does not usually need to operate on the model of prostitution, that is, the corrupt buying of favors; rather, it gains favors by its innate seductiveness. Think of Machiavelli who claims that Lady Fortuna lets herself be won by the most audacious princes. Adams, applying the lesson to republican regimes, found to his distress that Lady Liberty lets herself be captivated by the oligarchic few. Democratic citizens— known as “the many” to philosophers from Aristotle to Machiavelli—rarely give the plutocrats the slap in the face they deserve for their liberty-takings.

This is why Adams thought the liberal ideologues of his day, especially the French ones, but the American democratic-republicans too, were dangerously naïve. They believed that aristocracy was an artificial creation that could be dismantled. The only distinctions that would matter in the new world were the solid ones of talent and virtue. Adams suspected that “the idealization of talent could only serve to cloak the reality of oligarchic power.” Meritocracy is just oligarchy by another name.

Today, many are starting to have Adams-like suspicions about meritocracy. Inequality—inevitably characterized as “increasing”—is the topic du jour. However, we are no more insightful than the Jeffersonians were about the role our own elective affinities might play in this phenomenon. As Mayville points out, the solutions usually offered to restrain corruption and influence-peddling focus on the law and public policy. Just as Jefferson sought to strip away what he called the “tinsel aristocracy” by abolishing primogeniture, separating church and state through disestablishment, and endorsing publicly funded education, we propose such things as campaign-finance reform and the regulation of lobbyists. If Adams is right, however, then laws (even good laws) will always prove inadequate to address what Mayville nicely dubs “soft oligarchy.” What we really need is a sentimental education—an education in the surprising perversities of human nature.

And it does seem perverse that democratic peoples should be so awed by elite pedigrees and big bank accounts. Jefferson assured us that Americans, once properly educated, could be trusted to separate the meritorious from the meretricious (or “the natural aristocrats” from the “pseudalists”). Adams never believed a word of it. But he did think two things might be done. One would be direct: a constitutional design that would confine and check the refractory few. The other would be indirect: a plan to attach honorifics to offices as a means of steering public esteem away from wealth and toward the qualities actually needed for public service.

Adams had an inventive genius for constitutional architecture. Mayville explores Adams’ defense of bicameralism and a unitary executive. Adams envisioned the chief magistrate—the “one”—as the natural ally of “the many” against “the few.” The Senate he conceived as a place of dignified quarantine for those dangerous few. “Adams’s solution,” Mayville explains, “was to corral the most distinguished citizens into a single chamber—one part of government, thereby preventing them from dominating all of government.” While Mayville gives a nice account of the influence of Jean Louis De Lolme’s Constitution of England (1775) on Adams’ ideas, he ends up seconding Jefferson, who dismissed the notion that the Senate would become, in effect, “an ostracizing body,” in which the well-heeled are neutralized by enticing them to “trade power for pageantry.” Jefferson’s critique focused on the harm done by institutionally empowering the few. The Senate, he feared, would at least work mischief by blocking the House.

By following Jefferson’s critique too closely, Mayville fails to consider another possibility, namely that the main check upon the Senate would be internal to the Senate. Confirmation of this intuition might be found in the ethos of the Senate, which is so different from that of the House. Whereas the governing principle of the House is majority rule, the Senate, as a body of pseudo-noblemen, recognizes elaborate rules of deference and senatorial privilege, where each member is as weighty as the whole. Adams, I think, was on to something in perceiving that the Senate would be a self-checking institution. Indeed by now we see this may have gone too far, with our upper chamber, like the British House of Lords, reaching the point of inanition.

It’s also noteworthy that while one might have expected the Senate to be a launching pad for the presidency, it has not worked out that way. Only three individuals have moved directly from the Senate to the Oval Office, and in each case (Harding, Kennedy, and Obama) they were first-term senators. If a senator does not break out of that quarantine, he is doomed never to be President. Think of the fate of Daniel Webster or Henry Clay. The 20th century list of failed senatorial aspirants to the presidency is lengthy and impressive.[1] It seems that the institution does succeed, as Adams hoped, in unobtrusively molding individuals to fit within its horizon.

On the matter of titles for officeholders, Mayville does an admirable job of rescuing Adams from the ridicule that first greeted his seemingly outmoded suggestion. You’ve probably heard the story: When the question of how the president should be addressed came up in the first Congress, Vice President Adams, presiding as president of the Senate, proposed a high-flown title along the lines of “His Highness, the President of the United States of America and Protector of the Rights of the Same.” Adams reasoned that an elevated title would help attract worthy individuals to the office and inform both the public and the officeholder of the virtues essential to the performance of the office. His stubborn endorsement of the idea achieved little more than fastening upon him the charge of being an apostate from the democratic creed, suspected of desiring to return America to the bad old days of king and lords. (The incident also gave the satirists leave to designate Adams “His Rotundity.”)

Today, nearly everyone is on a first-name basis with everyone else, suggesting that democratic informality has triumphed. On the other hand, job titles have followed the path Adams recommended. The humble garbage man is now a sanitary engineer, and corporate vice presidents of this and that multiply at an alarming rate. We live in a land of titles, certificates, prizes, and ceremonies. You’ll never go out of business running a trophy supply house. Drawing upon his knowledge of the Roman republic and Baron de Montesquieu’s analysis of honor, Adams gave a great deal of thought to how the passion for distinction could be yoked to the public good. Perhaps honorific titles, attached to offices, could counteract the tendency of a commercial people to worship nothing but money. He called this “a language of signs” and hoped it could rival that other sign: the mighty $.

Throughout the book, Mayville helpfully compares and, more often, helpfully contrasts John Adams to Alexis de Tocqueville. More might have been said, though, about their fundamental agreement as critical friends of democracy. Toward the very end of Democracy in America, Tocqueville speaks of the special need that democracies have for forms and formalities, notwithstanding their instinctive distaste for them. Tocqueville describes “the principal merit” of forms as erecting “a barrier between strong and weak”—a barrier that protects the weak. The deferential forms of address recommended by Adams are a perfect illustration of Tocqueville’s point. Calling the berobed judge “your honor,” far from being undemocratic flattery, instead serves the republican purpose of reminding public officials of their duties toward the public. As both Adams and Tocqueville knew, it is illusory to pretend that representative government does away with the distinction between those with power and those without. For the sake of maintaining democracy, Tocqueville advised democratic statesmen to cultivate “an enlightened and reflective worship” of forms and formalities. Adams did precisely that.

Of course, the fact that his statesmanly choices were so unpopular must give us pause. Mayville rejects the view of Adams as a “conservative apologist for class privilege.” That seems right. However, Adams, like Tocqueville, still seems to me to be a conservative of some sort: a conservative liberal or a liberal conservative. Though he was committed to the experiment of representative self-government, Adams could be awfully frank about the deficiencies of the demos. It’s hard to be recognized as a true friend of democracy when you say things like “Democracy is a distemper, . . . when it is once set in motion and obtains a majority, it converts everything good, bad, and indifferent into the dominant epidemic.”

The wicked-smart, biting wit of Adams didn’t endear him either. In a letter to Benjamin Rush, Adams admitted that his friends “used to tell me I had a little capillary vein of satire, meandering about in my soul, and it broke out so strangely, suddenly, and irregularly that it was impossible ever to foresee when it would come or how it would appear.” This astringent quality, which makes Adams vastly entertaining to read, didn’t strike its victims as so charming when he mocked the inveterate naiveté of the believers in Progress. Adams preferred his progress with a lower-case “p”—the kind of progress that doesn’t come with any assurance from History, but depends rather on a clear-eyed assessment of human nature, searching thought about the art of government, and prudent management.

Finally, Adams argued for the continuing relevance of the distinction between the few and the many, even as he, like Machiavelli from whom he learned so much, sought ways to foil the power-hungry few. The many—at least in modern times—don’t like to hear that there is another class of beings different from themselves. It bears noting that Adams’ take on the few and the many is not quite the standard one, since he finds the grounds for superiority to be so various. Superiority (or “aristocracy”) he defines as the ability to “command, influence, or procure” one vote beyond your own. This is an oddly democratic definition of aristocracy, resting as it does on a social permutation of “one man, one vote.” Some voters put their votes at the disposal of others because of the qualities they manifest. In a letter to John Taylor, Adams gives a fascinating list of the instrumentalities by which votes might be commanded. He mentions acquired qualities such as virtues, talents, learning, and eloquence, but also natural gifts like face, figure, grace, attitude, and good fellowship, along with conventionally valued traits like wealth and good birth. He even mentions such questionable modes as intrigue, drunkenness, and debauchery (yes, there is a womanizers’ vote that can be tapped by the likes of Bill and Donald).

In a wonderful section of the book, Mayville explores the “aesthetic” dimension of social distinction. He begins by noting the unique prominence of “beauty” in Adams’s account of the sources of aristocratic power. Here especially is a form of influence that “grow[s] out of the constitution of human nature.” Our glittering celebrity culture—and its takeover of electoral politics—would not have surprised, though it surely would have distressed, John Adams. After all, in an 1807 letter to Benjamin Rush, he listed among the “Talents” of that paragon of virtue, George Washington, “A tall Stature, like the Hebrew Sovereign chosen because he was taller by the Head than the other Jews.” Perhaps Adams was still chafing at his wife’s enthusiastic raptures in 1775 about Washington’s “Majestick fabric!”

All of this is to say that, for Adams, the deepest threats to popular government lay in the sentiments of the people. Drawing out the lesson, Mayville suggests that we ought to enlarge our current concern over inequality “to consider how modern democracies succeed or fail to divert public admiration away from wealth.” I’m reminded again of Tocqueville who, like Adams, was greatly interested in discovering counterweights to commercial values. Mayville has established how Adams tried to balance the scales with appeals to honor. Tocqueville too spoke favorably of pride, but he also looked heavenward. Tocqueville singles out religious belief as the best antidote to materialism (materialism being understood as an inordinate desire for material goods, as well as a metaphysical belief that matter is all there is). Tocqueville argues that “a taste for the infinite, a sentiment of greatness, and a love of immaterial pleasures” are needed to sustain democratic liberty and, further, that the source of these political goods is belief in the immortality of the soul.

There is very little in Mayville’s book about religion, other than one footnote stating Adams’ worries about the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution. I wonder whether there is more to be found in Adams about religion as a useful means to restrain or redirect the idolatry of wealth. It is remarkable how many of the letters that Adams writes to Jefferson touch on religious questions and speculations. Repeatedly, Adams denounces the atheism of the philosophes. In another letter, he states his own “Creed and Confession of Faith.”

A preoccupation with the links between what Tocqueville called “the spirit of religion” and “the spirit of liberty” appears in Adams’s published works as well. Listen to the very end of his Discourses on Davila:

Let us conclude with one reflection more which shall barely be hinted at, as delicacy, if not prudence, may require in this place some degree of reserve. Is there a possibility that the government of nations may fall into the hands of men who teach the most disconsolate of all creeds, that men are but fireflies and that this all is without a father? Is this the way to make man, as man, an object of respect? Or is it to make murder itself as indifferent as shooting a plover, and the extermination of the Rohilla nation as innocent as the swallowing of mites on a morsel of cheese?

Like Tocqueville, Adams worried about the moral and political dangers of nihilism. His fears about elites extended to the new secular priesthood of scientists who paid obeisance to nothing but “almighty chance.”

The letters that Adams and Jefferson exchanged were clearly written with a view to the judgment of posterity. Speaking for that posterity, Mayville has delivered a considered and fair verdict, awarding Adams the prize for prophetic power. Two centuries later, do the American people elect the “real good and wise,” as Jefferson promised we would? If not, where does the fault lie? Do we need updated versions of the economic, educational, and legal reforms that Jefferson recommended? Or is Adams right that “the many” themselves will acknowledge no other “Aristoi” but that based on birth and wealth?

In an election season that pits the Clinton dynasty against the plutocrat Trump, it seems legitimate both to marvel and to be chagrined at the perspicacity of Adams. I guess we will see whether our complex constitutional structure still works to render these “most difficult animals” serviceable to the cause of republican liberty—or whether we will instead succumb to what Machiavelli called “fatal families born for the ruin of their country.”

[1] See Noemie Emery’s “The Young and Restless: Senators in a Hurry,” Weekly Standard, February 15, 2016.