Would You Like Fries with that Sturm und Drang?

Is it possible for a film’s musical score to undermine the film it supposedly serves? In the case of The Founder, the answer is yes.

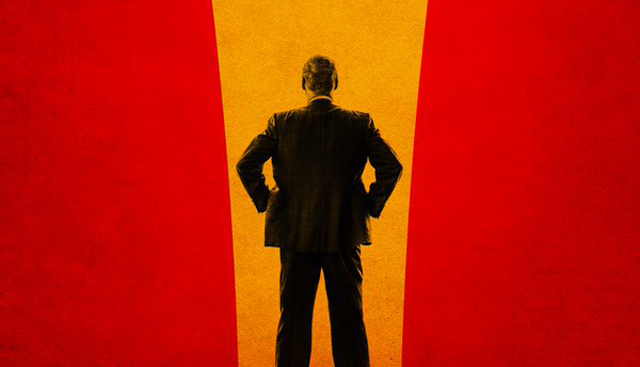

The Founder stars Michael Keaton as Ray Kroc, the Chicagoan who took a small hamburger stop called McDonald’s and turned it into a billion-dollar global brand. The film depicts Kroc as an unstoppable force of nature but also a ruthless and dishonest businessman. Keaton’s portrayal is fantastic, his character at once a spry, hyper-focused visionary and a heartless SOB.

But then there is the musical score by Carter Burwell. Burwell’s music, which fills nearly every sequence of the film, is a drag on the story, imposing a discordant and melancholy tone on what is essentially a bright tale of all-American persistence. While plot, direction, and acting all work to create a dynamic atmosphere in The Founder, the music is plodding, steadily dragging us downward. It’s almost as if the filmmakers couldn’t fully bring themselves to celebrate Kroc, a genius American businessman.

For anyone who thinks that a film’s score is not crucial to how we experience it, imagine The Godfather without Nino Rota’s indelible cues, Lawrence of Arabia minus Maurice Alexis-Jarre’s music, or Star Wars without John Williams’ soaring orchestration. Music in a film—not just what kind, but at what moments it comes in and with what frequency—is no small issue. And in The Founder, it may have been used to undermine what should have been a fairly straightforward story.

It’s also a fairly well-known one. In 1954, a middle-aged traveling salesman hawking milkshake machines gets an order from a burger stand called McDonald’s in San Bernardino, California. McDonald’s and its “speedy service” concept—“hamburgers in 30 seconds, not 30 minutes”—is the brainchild of brothers Mac and Dick McDonald (wonderfully played by John Carroll Lynch and Nick Offerman). Kroc, a man who will not take “no” for an answer, convinces the brothers to let him franchise McDonald’s. Then Kroc buys the franchise out from under them.

The scenes of Kroc developing his obsession are some the best in The Founder. After realizing that several franchise managers are not upholding standards, Kroc begins to recruit people he knows have virtue: a married Jewish man whose wares are volumes of the New Testament (“What’s a Jew doing selling Catholic Bibles?” “Making a living.”); a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars peddling vacuum cleaners to support his wife; an especially hardworking teenager who becomes a millionaire by following Kroc’s orders. In exchange for an attention to quality and customer service, these people get rich.

“Three words,” Kroc says to potential employees. “McDonald’s. Is. Family.” It’s an exhilarating depiction of the miracle of prosperity that happens when American ingenuity is wedded to basic decency and hard work.

Director John Lee Hancock wisely just gets out of the way, letting the veteran Keaton carry the film and occasionally interjecting lovely scenes of the golden American West, a dappled incubator of Kroc’s big dreams. Screenwriter Robert Siegel also keeps things simple, as befits the personalities of the characters, who were plain-spoken if occasionally intense. The supporting cast is all fine, mostly just reacting to Kroc, the unstoppable cyclone of positive thinking.

It is here where the right music could have lifted The Founder off the ground. Kroc’s obsessive-compulsive attention to expansion deserved the percolating rhythm of bebop jazz, which also would have been appropriate for the era depicted. They also might have used some Chuck Berry or Buddy Holly tracks, as the early rock ’n roll of that time was expressive of the grand optimism and even mysticism of the middle of “the American Century,” as it was called.

The unaccountably dour tone of the music is addressed by composer Burwell on his website, where he comments:

I once saw Michael Small speak about how his score to the dystopian political thriller The Parallax View used patriotic instrumentation to create a discomfort in the audience, and I wanted to take a similar approach here. Maybe not so jaundiced as Small’s score, but still portraying Kroc’s relentless drive as patriotic or militaristic in tone.

Burwell goes on:

The director, John Lee Hancock, wanted to be sure everyone was on board with Kroc as a character first. So the snare drums don’t start until Kroc starts recruiting—first the McDonald brothers and then his franchisees. Prior to that I play an off-kilter version of Americana, to suggest that he’s a traditional mid-50’s mid-Westerner with a dark twist. For the sound of the heartland I used guitars, mandolin, woodwinds and strings. A musical voice that seemed to work for his inner voice was piano. Specifically an upright piano like the spinets that were so popular in middle American living rooms of that time.

This “dark twist” approach might have worked well if Burwell had saved it for the scenes where Kroc shows his dark side. For example, once his business model has caught on, he demands that McDonald’s make its signature milkshakes with powdered milk. Also we see him sitting at the dinner table coldly informing his first wife Ethel that he wants a divorce. He is duplicitous in several of his legal dealings.

But whatever Burwell may say, this movie is no Parallax View (1974). The famously paranoiac post-Watergate thriller argued that an evil American shadow organization was setting up patsies to assassinate our leaders. No doubt the hamburger magnate was not a perfect man—indeed his entrepreneurial efforts may well have contributed to obesity and diabetes in the United States and beyond our shores—but he was no threat to the political order.