The Ring of Buckley

Great writers, thinkers, and men are rare. William F. Buckley, Jr. qualifies by any number of measures and in any number of areas.

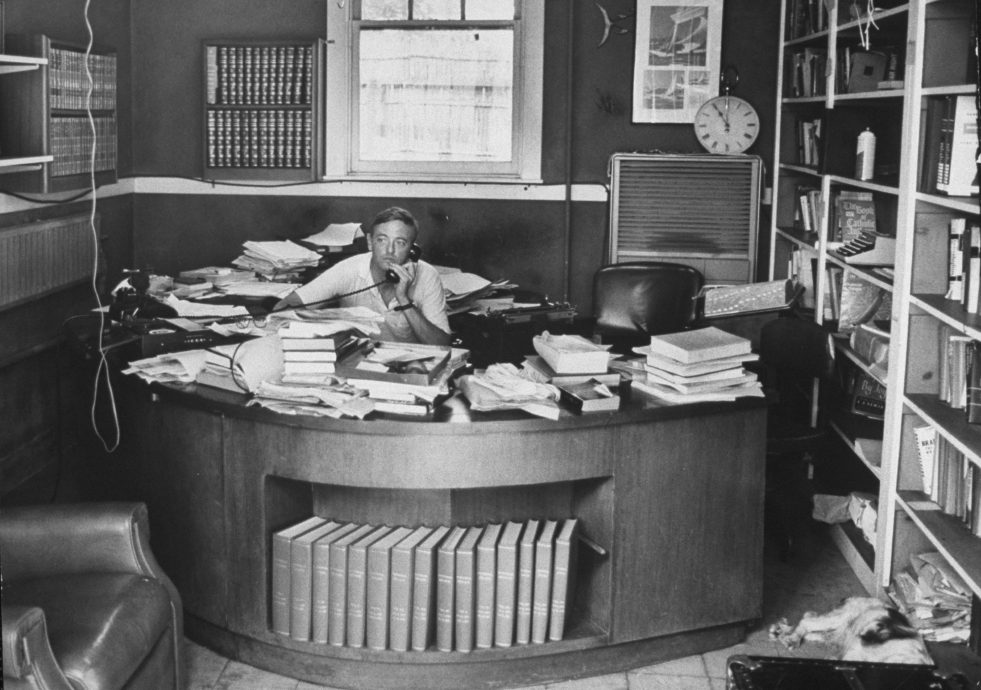

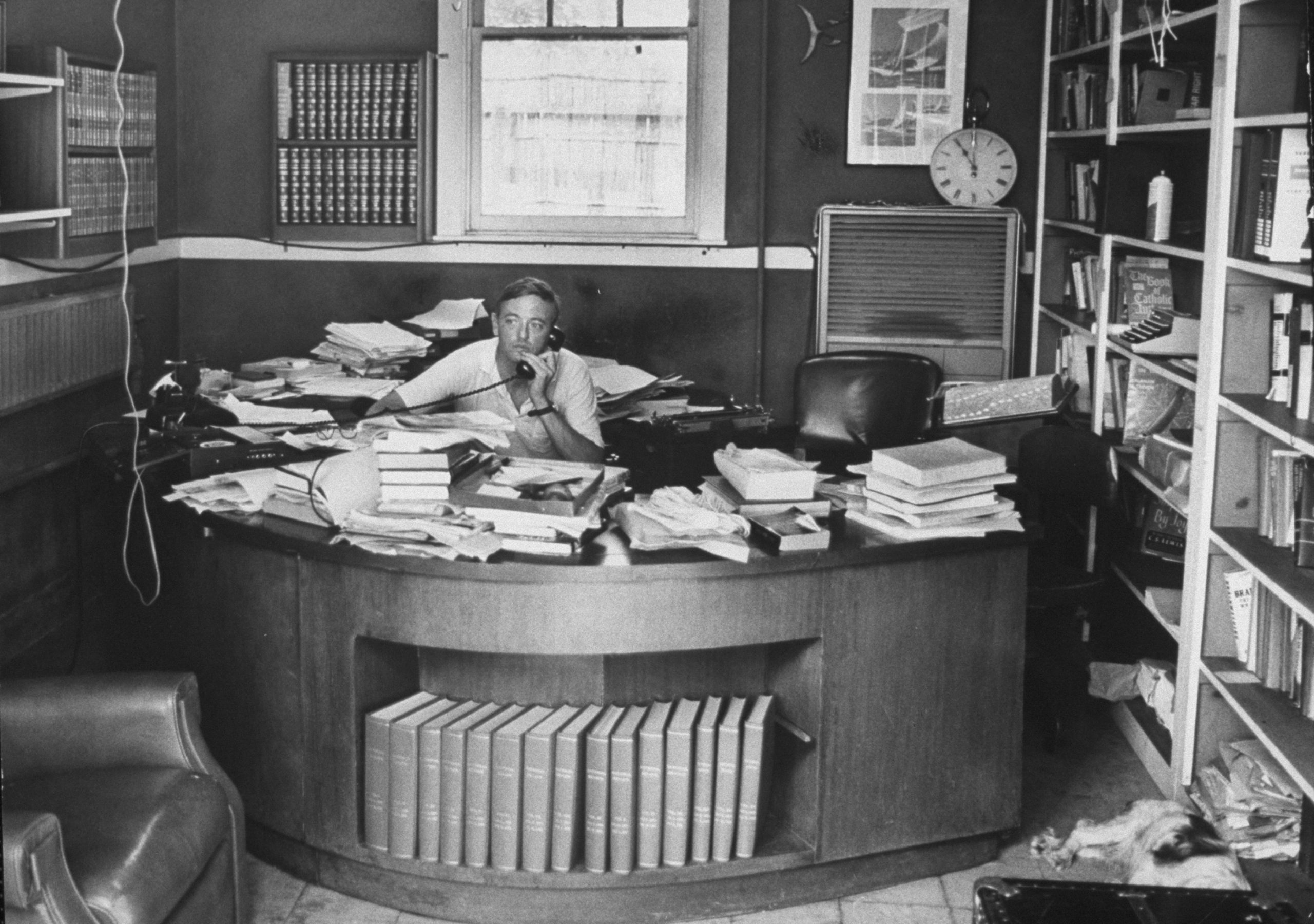

Buckley was the leader of the conservative intellectual movement of the 20th century, most notably through National Review, the incomparable magazine he founded in New York City in 1955. He was a prolific writer of political polemics and playful prose. He was the host of Firing Line, the longest-running single-host public affairs program in American television history (and the debates on Firing Line have seen a renaissance through the miracle of Youtube). He was a principled candidate, on the Conservative Party line, for the mayoralty of New York City. He was a skilled sailor. He wrote popular novels. He was a scholar and a gentleman.

In short, he was the kind of man who fit the 20th century archetype of the aristocratic WASP (though he was not one), not by dint of his name or inheritance but because of his intellect, work ethic, and achievements.

Often when one studies history, one finds that exceptional individuals have an uncanny ability to discern the true nature of others. The great statesmen read other people well because they must work with others to achieve their ends—probing and prodding for strengths and weaknesses, and knowing when to cajole and when to criticize. The great entrepreneurs excel at meeting the needs of customers, or by discovering or anticipating a need that customers never knew they had. The great artists—and I use that term broadly—are diligent observers of mankind and of the human soul, bringing forth its essence in their works.

Buckley’s contributions—partly political, partly entrepreneurial, and partly artistic—were influenced by the impressive talents with whom he surrounded himself. He cultivated his friends and enemies well. A Torch Kept Lit: Great Lives of the Twentieth Century collects his writings about other compelling contemporaries, profiles (eulogies, actually) that limn the character traits and quirks that made these individuals who they were.

The project of Fox News Washington bureau chief James Rosen, A Torch Kept Lit is broken up into six sections covering more than 50 men and women: “Presidents”; “Family”; “Arts and Letters”; “Generals, Spies, and Statesmen”; “Friends”; and “Nemeses.” There is great variety here. The eulogized include figures as diverse as Golda Meir, John Lennon, Whittaker Chambers, Elvis Presley, and Vladimir Nabokov. Throughout, we see Buckley’s wry wit, signature verbosity, and ability to turn a phrase. We also see magnanimity and tenderness toward his fellow human beings—and, occasionally, harsher judgments than one might have expected, rendered on those one might have assumed were his friends.

Of Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic former Governor of Illinois and United Nations ambassador under President Kennedy, Buckley says that he was “born to be defeated for the presidency.” Stevenson of course was defeated by Dwight D. Eisenhower twice in the general election, and then lost the Democratic nomination for presidency against Kennedy in 1960. But Buckley also criticizes Eisenhower, his fellow Republican, for his deviations from conservative orthodoxy. Nevertheless, he notes that Ike was “manifestly infected with a lifetime case of patriotism.”

The piece on Winston Churchill ends surprisingly vindictively. Of the former Prime Minister, who died in early 1965, Buckley writes:

He turned over the leadership of the world to the faltering hands of Americans who were manifestly his inferiors . . . and contented himself to write dramatically about decisive battles won for freedom . . . battles whose victory he celebrated vicariously, having no appetite left to fight real enemies, enemies whose health he had, God save him, nourished by that fateful shortage of vision that, in the end, left him, and the world, incapable of seeing that everything he had said and fought for applied alike to the Russian, as well as the German, virus. May he sleep more peacefully than some of those who depended on him.

Of intellectual sparring partner John Kenneth Galbraith, he writes:

He was voted the third most influential economist of the 20th century, after [John Maynard] Keynes and [Joseph] Schumpeter. I think that ranking tells us more about the economics profession than we have grounds to celebrate . . . Forget the whole thing . . . the Nobel Prize nominations, and the economists’ tributes. What cannot be forgotten by those exposed to it is the amiable, generous, witty interventions of this man, with his singular wife and three remarkable sons, and that is why here are among his friends, those who weep that he is now gone.

His eulogy of the influential New York Times editor A.M. Rosenthal is particularly glowing. He writes that “We profit, endlessly, from his ingenuity and perspective.”

In his tribute to the libertarian economist Milton Friedman, we find that Buckley was devastated not primarily because of the blow Friedman’s death landed to liberty, but because of the “grief for the loss of a person” of his “sometime skiing buddy.”

Of the historian and Democratic Party elder statesman Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Buckley writes:

I always regretted that we didn’t become friends, because the thousands who succeeded in doing so found friendship with Arthur Schlesinger very rewarding. For one thing, to behold him—listen to him, observe him, read him—was to coexist with a miracle of sorts.

Buckley could be charming and acerbic all at once, and that quality shows up here, particularly in the eulogies of Presley and Nabokov. The punchy lines in the book are endless. Along the way, editor Rosen provides helpful introductions to each piece, tracing the various professional and personal relationships Buckley fostered over time, in debate, over dinner, and on the ski slopes. The volume provides a context that lends further color to the Buckley persona, leaving the reader with a real sense of who Buckley was, and how he lived his life.

Last but not least, we get a treasure trove of choice anecdotes. For example, Buckley reveals the long-running inside joke he had with President Reagan regarding serving as his “ambassador” to Afghanistan. Buckley describes this fictional role in playful letters throughout the eight years of Reagan’s presidency. The Gipper would always address Buckley as “Mr. Ambassador.”

Another anecdote concerns William F. Buckley, Sr., who acquired a supply of wine in the vineyards of France that had reportedly been destroyed by German bombs during World War II. A later report indicated the libations had been stolen. But lo and behold, come the end of wartime the Buckleys received correspondence saying the bottles were all intact and would be delivered to the family home in Sharon, Connecticut.

Buckley’s father’s collection would prove invaluable—yet he would neglect to include it in the assets he bequeathed to his children, according to his son, apparently having thought nothing of its value or importance. While Buckley Jr. notes that the rest of his father’s property was quickly drawn down throughout the years, the wine continued to flow. For 20 years, Bill and his siblings would imbibe their father’s wine, “those lovely things that had slept peacefully, gaining flavor and enhancing their power to delight, through a world war and several occupations. It is a wonderful way to remember one’s benefactors, isn’t it? To drink wine in their memory?”

In some ways, this is an apt metaphor for Buckley’s life and the record he has left of it for us.

At once didactic, biographical, and entertaining, A Torch Kept Lit is not a work of political philosophy. But from it we take the lesson that republics require virtuous men. In William F. Buckley we see the quintessential virtuous republican figure in both public and private life: A picture of honesty, decency and patriotism to which we can all aspire.