Return to Marbury

The travel ban case is headed to the Supreme Court by way of the once redoubtable Fourth and always activist Ninth Circuits, leaving revisionists to wonder how it might have unfolded had it made its way upward through Judge William H. Pryor’s Eleventh. Pryor’s view of the judicial role exhibits appropriate assertiveness within its sphere and a fitting humility beyond it.

Pryor’s perspective might consequently help advocates of judicial engagement and restraint move beyond one of the central difficulties in their disagreement, which is the tendency to veer into judicial supremacy in the former case and impotence in the latter. The travel ban illustrates one dimension of the problem, which is what happens when a court issues a ruling other branches believe impinges on their authority. Would the Trump Administration be immovably bound by it?

Recently in this space, I argued that constitutional meaning was liquidated by conversation between the branches rather than by the discrete and final view of the courts, with the judiciary considered as the last stop on a temporal line. I stand by that conclusion, but Pryor’s writings provide a subtler and richer account of the judicial role.

The account begins where I erred, which was in a truncated and flawed account of Marbury v. Madison. Using Marbury as an illustration of how presidents and courts once confronted each other more forthrightly, I repeated the strain of scholarship that holds that Chief Justice Marshall willfully misread Article III of the Constitution in order to avoid a confrontation with President Jefferson while manufacturing grounds for establishing the power of judicial review.

Pryor’s 2011 essay, The Unbearable Rightness of Marbury v. Madison: Its Real Lessons and Irrepressible Myths, published in the Federalist Society’s journal Engage, dismantles that account. He argues that Marshall’s reading of Article III is in fact the most natural one. Most important—and here I agree with Phillip Hamburger and him and ought not to have suggested otherwise—Pryor notes that judicial review preexisted Marbury.

It is all the more important to get this point right because of the reasons generations of scholars have found it useful to get it wrong. Pryor shows that Marbury was first extensively cited by late 19th century conservatives to justify judicial imposition of laissez faire economics. Then, in a backlash against judicial review, 20th century Progressives propagated the myth that Marbury had manufactured the power on spurious grounds. The Warren and Burger courts then accomplished “[t]he completion of the Marbury myth” in order to establish judicial supremacy, which was abetted by legal scholars who varnished the lore with “a positive spin.”

In all, Pryor catalogues three Marbury myths: first, that Marbury invented judicial review, which he notes preexisted it; second, that Marbury established judicial supremacy over constitutional meaning; and third, that Marbury is an instance of judicial activism.

Taken together, Pryor’s treatment of these myths shows a view of the judicial role that is simultaneously assertive within its realm and restrained beyond it.

The first illustrates the judiciary’s oath-bound duty to interpret and apply the law.“The second myth—that Marbury established the judiciary as the supreme and final authority in determining the meaning of the Constitution—is contrary to the language of the decision itself,” Pryor writes. Rather than establishing the supremacy of the Court, he observes, Marbury establishes the supremacy of the Constitution, which the decision calls “a rule for the government of Courts, as well as of the legislature.”

Marshall merely interpreted “a statute that governed the Supreme Court and decided that the statute was unconstitutional as applied to Marbury’s petition” but “did not say anything negative about the duty of other branches to interpret the Constitution within their own spheres of responsibility.”

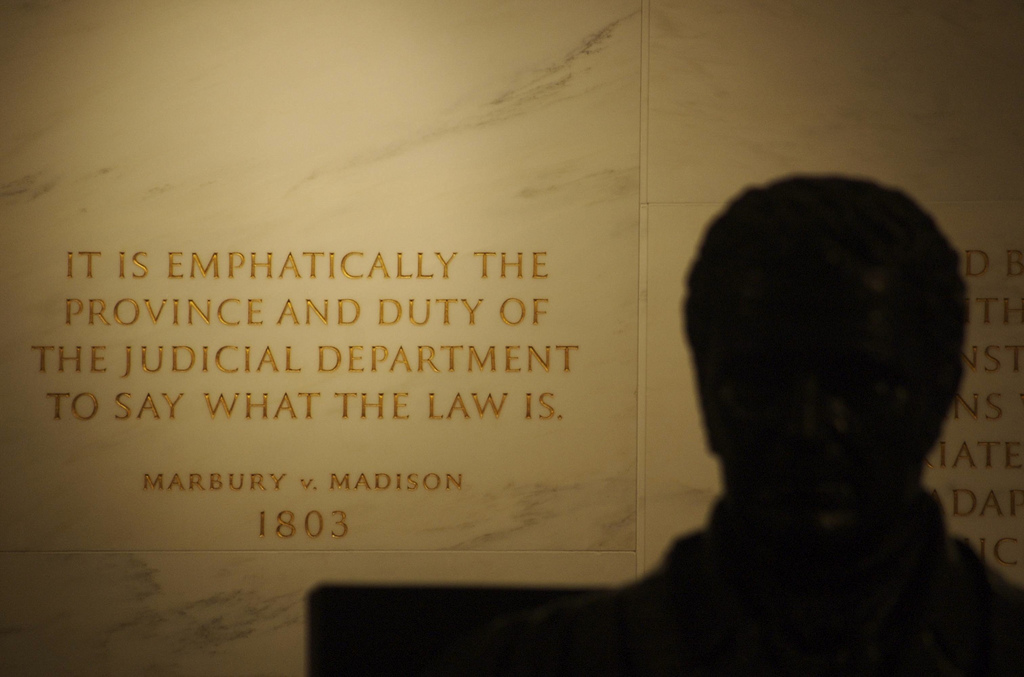

Instead, Marshall believed the authority of judges was limited to “cases,” which, as Pryor notes, the much overlooked sentence following Marbury’s famous dictum indicates: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must of necessity expound and interpret that rule.” (Pryor’s emphasis)

James Madison seems to have meant something similar in seeking toward the end of the Constitutional Convention to confine judicial authority to cases “of a judiciary nature,” which the delegates declined to do on the grounds that such a limitation was so obvious as not to require specification. In Marbury, as Pryor shows, this judiciary nature is especially confined, since the law being interpreted pertains to the authority of the courts.

Thus the third myth: that Marbury is an activist decision. Pryor explains:

When the judiciary engages in judicial activism, it usurps the constitutional power of a political branch and fails to adhere to the constitutional text. Judicial activism is about wielding judicial power for political ends. In Marbury, the Court obeyed the Constitution and exercised restraint by refusing to compel a political officer to act or refrain from acting. The Marbury Court in no way frustrated popular will.

Note the relationship between the second and third myths: In Pryor’s Marbury, the judiciary exercises its authority only in particular cases, constrained by law and not as a final arbiter. Other branches are fully entitled to assert their own views of constitutional meaning from within their own realms.

How so? And how might that play out in the case of an adverse ruling like the travel ban? Pryor’s 2008 Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy essay Moral Duty and the Rule of Law provides some guidance.

There Pryor explains the case he brought to dislodge Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore for disobeying an injunction of a federal court regarding a Ten Commandments display on public property, distinguishing “defiance of a final order of a court” from President Lincoln’s “political opposition” to Dred Scott.

At several points, Lincoln distinguished between the binding nature of the Dred Scott ruling on the parties to the case and its force as precedent. Pryor notes that President Lincoln consequently “required his administration to issue a passport to a black student and a patent to a black inventor.” But these challenges to “the continued application of Dred Scott” did not violate the specific and final order of a Court in, crucially, a particular case—the kind where, we recall from his treatment of Marbury, judicial power is naturally at its peak.

The difference between Moore and Lincoln helps to illuminate President Trump’s options. He cannot—and has not—violated a specific injunction. But he is free to challenge that injunction not merely judicially but politically. He can seek the enactment of new laws and urge the reconsideration of the case. Importantly, he can also refuse to recognize its reasoning as an abstract restraint on future decisions. In addition, he can appoint new justices. He could do worse than Pryor, whose view of Marbury nicely situates him between absolutist advocates of judicial engagement and judicial restraint.