Karl Polanyi’s Irrelevance to Today’s Policy Debates

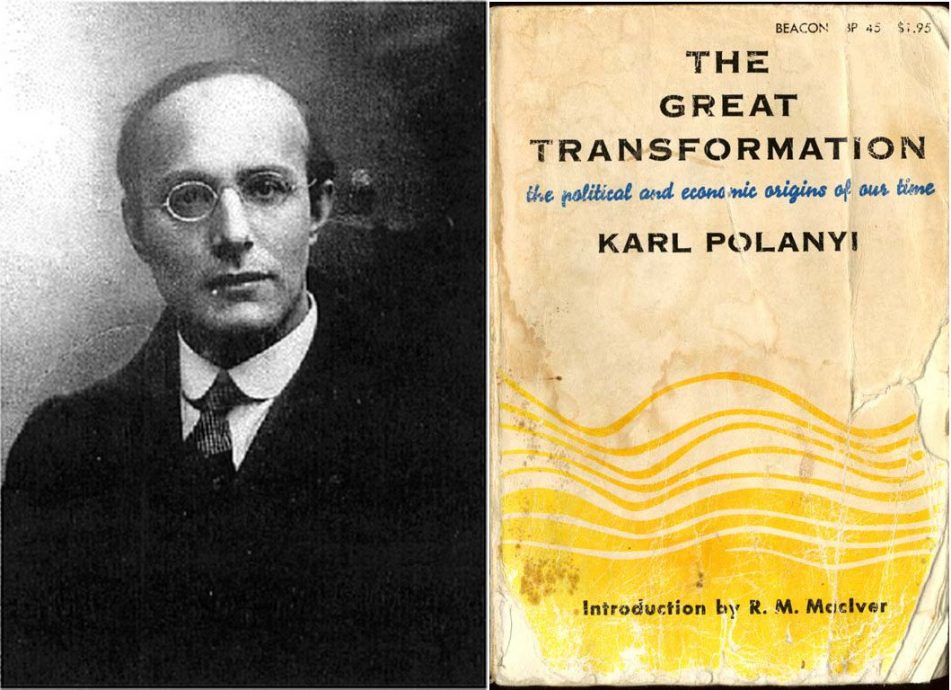

The increase in globalization over the last couple of decades, and the Great Recession, has spurred interest and attention in Karl Polanyi’s book, The Great Transformation. Republished in 2001 (and in 1957), scholars such as Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz (who wrote a preface to the 2001 edition), historians of the American “market revolution” and of social thought have pressed the book’s argument once again into service to speak to current economic events. The problem is, Polanyi declared the transformation already ended in the mid 1940s.

Polanyi intends The Great Transformation to be a descriptive, even predictive, work. He does not intend the bulk of it (the last chapter excepted) to be a work of normative political theory. He details the rise of a totalistic “market society” in the 19th Century, and he describes its fall in the 20th Century. It’s this last bit that gets overlooked: Polanyi argues that the political and social elements of society responded naturally to the totalism of market society and society ended the “self-regulating market” by the time he wrote the book in 1944. This argument in Polanyi’s work is almost always neglected by those purporting to apply it to more-current events such as the great recession of 2008 and globalization more generally. Yet the argument that market society has been definitely ended is central to Polanyi’s book. It can’t be passed over by friend or foe and still do justice to his argument.

Polanyi’s argument in The Great Transformation has several integral parts. One is his discussion of the rise and fall of what he terms “market society,” and the causes of that rise and fall. By “market society” Polanyi does not simply mean a society with markets in it. Indeed, for Polanyi, an economy might have lots of markets in it and yet not constitute a “market society.” As he writes, “the end of market society means in no way the absence of markets. These continue, in various fashions, to ensure the freedom of the consumer, to indicate the shifting demand, to influence producers’ income, and to serve as an instrument of accountancy . . .”

What he means by “market society” is very specific: it is a “self-regulating market,” meaning that the market autonomously sets the prices of labor and land and the gold standard is the only accepted basis for money. Polanyi repeatedly makes clear that all three need to exist in tandem, and exist autonomously from political or social control, for Polanyi’s market society to exist. He writes,

There is a sense, of course, in which markets are always self-regulating, since they tend to produce a price which clears the market; this, however, is true of all markets, whether free or not. But as we have already shown, a self-regulating market system implies something very different, namely, markets for the elements of production – labor, land, and money.

Polanyi argues that the subordination of society to the self-regulating market results in the commodification of human relations (“labor), and of relationships between people and the physical environment (“land”). As he writes,

For Polanyi, totalizing markets for labor, land, and money subordinate human relationships to a, literally, inhuman and inhumane system, meaning a process that, intentionally, cannot value humans or their relations except through prices determined by the market. This results, he writes, in alienation, anomie, and degrading poverty (which is argues is distinct from merely being poor in ages past). These in turn foment personal and social pathologies.

The thing is, for Polanyi, civil society naturally reacts to these pathologies by killing off market society (even while continuing to use markets, albeit, socially nested markets). This is not simply an incident to his larger argument. For one, Polanyi contrasts what he styles as the natural reaction of society to the brutality of the self-regulating market system, with what he argues was the artificial political and legal creation of the self-regulating market itself. (This he contrasts with Adam Smith’s narrative of the naturally-evolving market system.) Secondly, Polanyi argues that, in more-brittle political systems, fascism developed primarily in response to the devastating social breakdown created by market liberalism.

Polanyi leaves no doubt that society has responded to and ended the market system. He means this not as aspiration, but as accomplished fact:

“In retrospect our age will be credited with having seen the end of the self-regulating market.”

“Nineteenth Century civilization [with its self-regulating market] was not destroyed by the external or internal attack of barbarians; its vitality was not sapped by the devastation of World War I not by the revolt of a socialist proletariat or a fascist lower middle class. Its failure was not the outcome of some alleged laws of economics such as that of the falling rate of profit or underconsumption or overproduction. It disintegrated as the result of an entirely different set of causes; the measures which society adopted in order not to be, in its turn, annihilated by the action of the self-regulating market.”

“Since the working of such markets [in labor, land, and money] threatens to destroy society, the self-preserving action of the community was meant to prevent their establishment or to interfere with their free functioning, once established.”

“But how did the inevitable actually happen? How was it translated into the political events which are the core of history? Into this final phase of the fall of market economy the conflict of class forces entered decisively.”

“Within the nations we are witnessing a development under which the economic system ceases to lay down the law to society and the primacy of society over that system is secured. This may happen in a great variety of ways . . . [but] the outcome is common with them all: the market system will no longer be self-regulating, even in principle, since it will not comprise labor, land, and money.”

“The passing of market-economy can become the beginning of an era of unprecedented freedom.”

So here’s the rub of this part of Polanyi’s argument for today: For Polanyi, the self-regulating market of market society must be all of one weave or it can’t work as its supporters and creators designed it to work. Thus, the regulations, taxes and subsidies of a mixed economy, even if that mixed economy employs and is comprised in large parts of markets, means, for Polanyi, that “market society” has been extinguished. When the market is controlled by the social and the political rather than controlling the social and the political, then market society does not exist. Period. All that remain are niggling prudential arguments whether in this case or that markets or intervention better achieve the public welfare

On his own terms, and integral to the argument of his argument, Polanyi’s analysis cannot today be deployed in response to proposals for less regulation, or freer trade, or fewer capital controls between nations. These proposed reforms may be better or worse on prudential grounds, but none can be implicated in Polanyi’s analysis, because none can come remotely close to establishing the market society Polanyi studied and described.