What do the French see in their Lady of Liberty?

The Violent Bear It Away

Political modernity’s focus on reason was intended to emancipate with great compassion the mind of man from the unstinting claims of prejudice and bigotry frequently found in religious institutions. So the narrative goes. But as Flannery O’Connor demonstrated in her literature, compassion and reason can be their own unrelenting terrors. The review by Joshua King of Liberty Fund’s new volume on the Encyclopédistes entitled Encyclopedic Liberty: Political Articles in the Dictionary of Diderot and D’Alembert, is an interesting and thoughtful review of yet another excellent volume in our publishing program. The focus on religion contains this statement:

Christian political intolerance generates conflict and cruelty that have slaughtered millions. A sociological study of population demonstrates that the Christian religion undermines the obligations the human species has to itself and produces institutional violence and oppression.

Obviously, the 18th century contributors to Diderot’s Encyclopedia confronted religious intolerance and knew well the consequences of internecine Christian fighting. Still, we shouldn’t forget the similar failures of the rationalist political project of modernity, which now evinces reason as the standard, or equality, or liberty, or scientific planning, with much of it held together by an iron fist that excludes what Russian patriot and anti-communist thinker par excellence, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, referred to as the moral heritage of mercy and forgiveness of the Christian West.

I’m not sure where the reviewer is merely presenting for us the anti-Christian views of Etienne Damilaville and the other Encyclopédistes or is joining his own thought to their critique. One has to chuckle at the use of “studies-show” to demonstrate that the Christian religion basically undermines the human race. More seriously, the monstrous evils worked by the political analogue of the Encyclopédistes has to be considered: the French Revolution, the first modern instantiation of state ideological terror. To say nothing of their communist descendants in the 20th century who really did murder hundreds of millions, with a special focus on Christians.

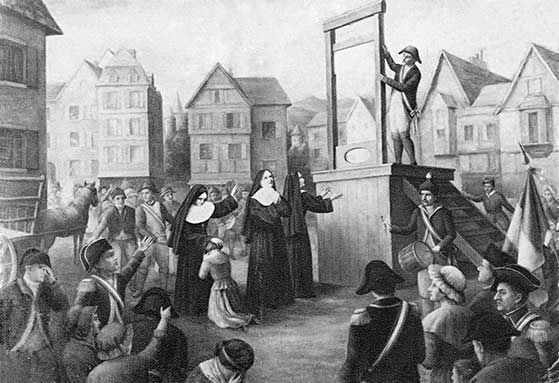

If one believes such things about Christianity and its adherents, then the murder and liquidation of many Catholic clergy and religious brothers and sisters, such as the massacre of the Martyrs of Compiègne, among other wicked examples during the French Terror, becomes, well, understandable. After all, a new age must be rationally constructed, one that gets beyond the “institutional violence and oppression” of Christianity, and that process will require, ultimately, that Christian blood be spilled. Even if Diderot and company didn’t know what they were setting up, surely the rest of us now do.

One recalls the contradictory rationalist claims of the French Revolutionaries, “liberty, equality, fraternity.” And because each one of these pressed to their rationalist, scientific, and encyclopedic limit ultimately eat each other, the words “or death” were soon added to the slogan to reinforce their non-negotiable nature. They dismissed what would later be pointed out by Tocqueville: that, if man refuses to acknowledge his soul and its requirements, then the consequences would emerge in striking and unpredictable ways. It was Christianity that broke us out of the iron grip of the polis and its civic monism because it disclosed to the soul that it had higher requirements than the republic. We aren’t merely polis fodder. Strangely, it was the French Revolution that tried to recreate such civic monism: as Robespierre put it,

the first maxim of our politics ought to be to lead the people by means of reason and the enemies of the people by terror…. The basis of popular government in time of revolution is both virtue and terror. There is nothing else than swift, severe, indomitable justice – it flows, then, from virtue.

For Tocqueville, a much wiser and more prudent thinker than the Encyclopédistes, knew that such abstract political moralizing could only lead to political terror. And we can also say that equality (Tocqueville again) wasn’t learned from philosophers but from God come to earth as man. That is, ultimately, why we accepted this teaching of man’s equality, which is nowhere apparent from mere reason. Reason, taken alone, surely contradicts the claims of equality among persons.

In another instance, the reviewer notes with seeming positivity the attacks on Catholic celibacy. It could hardly be the case that celibacy presented any real political problem in the forms of diminished population, as was asserted. Rather, the real problem is that of political atheism and its ultimate inability, rationalist theorizing aside, to produce real limits to state power. Precisely because there is no personal, providential God summoning the human soul to heights beyond political or earthly power, state power and its ability to replace God and work heaven on earth become all the more difficult to resist. What conceivable limits exist to human will and by way of extension what limits exist to human political power in this system? Reason itself contains no intrinsic meaning apart from an interpreter. As Eric Voegelin remarked, the mundane affairs of man, the profane acts of the city and its politics, only really take on meaning in the light of immortality and eternal reason.

This was the reason joined to faith that had to be liquidated.