The Rise of Formalism and the Decline of Chevron

Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council (1984) is one of the most cited and important cases in all of administrative law. It provides a two-step process for reviewing most agency adjudications. In the first step, the court decides if the statute clearly permits or prohibits the agency action. But if the statute is ambiguous, the court is to uphold the agency so long as the agency’s interpretation is reasonable.

In my view, Chevron represented a lack of confidence in formal methods of judging. If judges acting in good faith can use traditional methods of legal interpretation to determine the better meaning even of those provisions that may offer more than one possible reading, Chevron’s second step is otiose. Agencies may be good at policy but there is no reason to believe they are better than judges at interpreting facial ambiguity, particularly when those judges will have the benefit of the agency’s brief that can explicate technical terms in a statute and provide relevant historical references. Of course, one might worry that judicial ideology may distort judicial opinions, but one should worry even more that a combination of partisan politics and bureaucratic tunnel vision will distort agency interpretations. Judges as a group are more likely to be fair arbiters of meaning because they are generalists appointed by Presidents of diverse ideologies over decades.

Happily, with the greater judicial acceptance of formalist theories of law, the scope of Chevron seems to be shrinking even if the case is not likely to be actually overruled. The latest example of its diminution comes in an opinion this week from Justice Neil Gorsuch, the most formalist justice appointed in decades. The decision in Wisconsin Central, Ltd. v. United States turned on the question of whether a stock option was a form of “money reimbursement”—the phrase used in the Railroad Retirement Act of 1937. The government argued that the phrase was ambiguous and should therefore receive Chevron deference.

But Gorsuch sharply rejected this argument. The adjective “money” qualified “reimbursement,” he noted, and money was an ordinary medium of exchange, thus limiting reimbursements to those that provided mediums of exchange. No one buys groceries with stock options. Moreover, he observed that other statutes enacted at the time used the phrase “all reimbursement,” which contrasts with “money reimbursement.” Perhaps it was possible to interpret money reimbursement to cover stock options, but Gorsuch chose the better interpretation, not one that stretched the language and divorced it from its accompanying legal context.

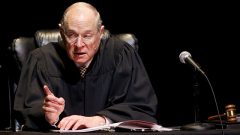

Also this week, Justice Kennedy, concurring in Pereira v. Sessions, complained that in immigration cases, courts were wrongly abandoning tools of statutory analysis to give unwarranted deference to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Board of Immigration Appeals. He too was signaling that there is often no need to go beyond the first step of Chevron—a judge’s determination that a statute is clear enough for him or her to discern if an agency’s action is permitted by that statute or not.

There remains a vigorous debate about the constitutionality of Chevron’s intrusion into the judicial function. But that debate may become less important in practical terms as the rise of formalism puts the judiciary back in the driver’s seat of administrative interpretation.