Artful Double-Dealing Made Clear, 55 Years Later

Go Set a Watchman owes the attention it has received to its connection with To Kill a Mockingbird, a novel whose importance in our national culture is difficult to exaggerate. For more than half a century, despite great changes in racial attitudes, politics, and literary fashion, its hero, Atticus Finch, has retained his stature as one of the great American moral standard-bearers. Only one person, it turns out, had the power to diminish his moral authority: his creator, Harper Lee—if indeed it was Harper Lee who made the decision to publish in 2015 an old manuscript once judged unworthy of publication.

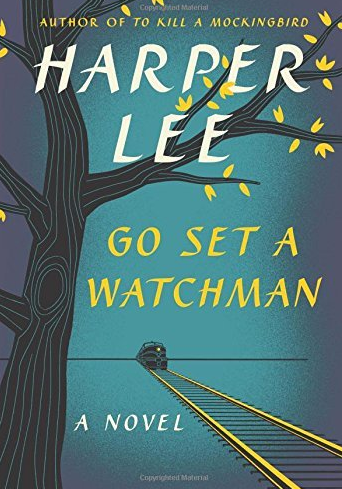

The dust jacket claims Go Set a Watchman “not only confirms the enduring brilliance of To Kill a Mockingbird, but also serves as its essential companion, adding depth, context, and new meaning to an American classic.” It would be more accurate to say that a consideration of the comparatively unsuccessful Watchman strengthens the suspicion that the success of To Kill a Mockingbird is due not simply to its portrait of a true moral hero but also to its ability to encourage its readers to feel they have attained the moral high ground without having done the hard work of confronting difficult questions. The central virtue of To Kill a Mockingbird as a work of the moral imagination is its presentation of a good man who does the right thing in the right way, without self-righteousness and without condemning others. The key failure of the novel is its double-dealing in regard to the great moral and legal principle of equality before the law.

In an eloquent speech defending a black man accused of raping a white woman, the Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird tells the jury Jefferson’s assertion that all men are created equal may be applied in mistaken ways,

But there is one way in this country in which all men are created equal—there is one human institution that makes a pauper the equal of a Rockefeller, the stupid man the equal of an Einstein, and the ignorant man the equal of any college president. That institution, gentlemen, is a court. . . . in this country our courts are the great levelers, and in our courts all men are created equal.

The speech is all the more powerful because Atticus concedes that there are many instances in which “equality” is irrelevant: “The most ridiculous example I can think of is that the people who run public education promote the stupid and idle along with the industrious—because all men are created equal, educators will gravely tell you, the children left behind suffer terrible feelings of inferiority.” Although the jury convicts the innocent black man anyway, almost all readers are able to tell themselves that they, at any rate, would have acquitted Tom Robinson. They would not fail to stand up for the great principle of equality before the law because of racial prejudice or for any other reason.

Except at the end of the novel readers are encouraged to applaud when Sheriff Heck Tate does not enforce equal justice. After Boo Radley kills the father of Tom Robinson’s accuser, Bob Ewell, the sheriff refuses to bring the perpetrator to justice, admitting to Atticus Finch that “If it was any other man it’d be different.” It is obvious to the sheriff that Boo Radley did it to prevent Ewell from physically attacking Atticus Finch’s children, Scout and Jem. The sheriff is willing to lie that the death was accidental—“Bob Ewell fell on his knife,” he claims—because Boo Radley is a recluse. Strangely, Sheriff Tate wants to spare the recluse, not from being convicted of murder, but from being lionized by the community: “All the ladies in Maycomb includin’ my wife’d be knocking on his door bringing angel food cakes. To my way of thinkin’, Mr. Finch, taking the one man who’s done you and this town a great service an’ draggin’ him with his shy ways into the limelight—to me, that’s a sin.”

Atticus, a principled lawyer, insists that equality under the law demands that whoever killed Bob Ewell be brought before a court even if it turns out to be his own son, Jem. The objections raised by Atticus (and seconded by the reader) are answered, however, in a conclusive way that leaves no doubt about the novel’s stand. Scout asks her father if summoning Boo Radley to court would “be sort of like shootin’ a mockingbird, wouldn’t it?” The answer is not in doubt; in the world of To Kill a Mockingbird, the worst thing one can do is shoot a mockingbird, symbolically or otherwise. The reader is encouraged to applaud the covering up of a killing; after all, the one killed was bad while the killer was good. As a bonus, the cover-up gives the novel a happy ending that compensates for the death of the wrongly convicted Tom Robinson in an escape attempt.

To Kill a Mockingbird thus allows its readers to have their cake and eat it, too—to affirm righteously the principle of equality before the law while occasionally disregarding it even more righteously. Because Go Set a Watchman is not as artful as To Kill a Mockingbird, the 2015 novel illuminates the skillful double-dealing of the 1960 novel.

In Watchman, Scout is a grown-up Jean Louise, and there is no mockingbird and no Boo Radley to undermine the principle of equality under the law or, in the words of the “slogan” she learned from her father, “equal rights for all, special privileges for none.” Here the alternative to equality before the law is not the appealing “mockingbird” motif but instead just plain old racial prejudice. When Atticus tries to explain why full equality under the law would not work, he begins to sound like Scarlett O’Hara from Gone With the Wind. He exclaims to Jean Louise, “Honey, you do not seem to understand that the Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people.” Scarlett felt the same way; the Yankees “did not know that negroes [sic] had to be handled gently, as though they were children, directed, praised, petted, scolded.”

In To Kill a Mockingbird Atticus Finch loves the South and respects his neighbors even as he opposes racism and insists on equality before the law. Racism seems to him a sort of inexplicable “disease” that he hopes Scout and Jem will not “catch.” He cannot understand “Why reasonable people go stark raving mad when anything involving a Negro comes up.” One might think the history of slavery, war, and segregation might illuminate the question, but to Atticus—and for the novel as a whole—the cause of racial prejudice is simply a mystery. Like a disease, it strikes some people and leaves others alone. This context-less “diagnosis” of racial animosity as a “disease” passes nearly unnoticed in Mockingbird; readers are likely to see this willful construction not as a sidestepping of history but simply as part of the sage lawyer’s non-judgmental compassion for all his neighbors, black and white.

In Watchman, on the other hand, the mystery is why Jean Louise is not racist when everybody else she grew up with in Maycomb, even her father, is, with the possible exception of her eccentric Uncle Jack. It is not because she has been living up North in New York. Having returned to Maycomb, she thinks to herself: “everything I learned about human decency I learned here,” while she “learned nothing” from her time in New York “except how to be suspicious.” The omniscient narrator reveals that her lack of racial prejudice has nothing to do with her father or anybody else. Like racism in Mockingbird, it is something acquired involuntarily, a medical condition: “all her life she had been with a visual defect which had gone unnoticed and neglected by herself and by those closest to her: she was born color blind.”

Uncle Jack, perhaps because he is a physician, understands.

“You’re color blind, Jean Louise,” he said. “You always have been, you always will be. The only differences you see between one human and another are differences in looks and intelligence and character and the like.”

The reduction of an individual’s racism or lack of racism to medical happenstance was made plausible in To Kill a Mockingbird by the moral prestige of Atticus Finch. It is revealed in all its simplistic reductiveness in Go Set a Watchman, where there is no character who can seize the imagination as Atticus does in Mockingbird.

In any case, Jean Louise is not entirely “color blind,” if that means what Uncle Jack says it does. In the very first paragraph of Watchman, Jean Louise feels “a delight almost physical” as the train enters the deep South and “when she saw her first TV antenna atop an unpainted Negro house; as they multiplied, her joy rose.” It’s not clear how the “color blind” Jean Louise can tell a “Negro house” from one inhabited by a white family; according to the text, she doesn’t see any people, so it seems it is the combination of a “TV antenna” and a lack of paint that leads her conclude that what she sees is a “Negro house.” (The presence of a television antenna is a more telling detail given the time of the novel, the mid-1950s, when television had not yet become ubiquitous.)

And if Jean Louise has a “visual defect” that leaves her “color blind,” her other senses are apparently unaffected. She smells “the musky sweet smell of clean Negro” when she enters the parlor of Calpurnia, the woman who, she thinks aloud, “raised me from the time I was two years old” but who now seems distant. The point of noticing such details is not to condemn Jean Louise as a closet racist but instead to demonstrate the superficiality of the notion that the ability to see people as individuals rather than as racial stereotypes could be understood as a medical condition—just as Mockingbird’s conception of racism as a “disease” is ultimately superficial.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a much better-written novel than Go Set a Watchman, but Mockingbird is not a great novel or even a very good one. It is profoundly duplicitous in that it appears to address difficult moral and political questions but finally allows readers to avoid them and enhance their own self-regard in the bargain. It does this so successfully that it is required reading in middle schools and high schools throughout the country, many of which ban The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, a novel that is not only Mockingbird’s literary superior, but one which remains more relevant to discussion of race in America than Mockingbird ever was. Go Set a Watchman lacks the cleverness of To Kill a Mockingbird, but just because of this lack, the 2015 novel illuminates some of the limitations of its famous predecessor.