Munich, 1933: The Good Bureaucrat, Josef Hartinger

Five months after Germany’s last free election of the interwar period—the National Socialists’ March 5, 1933 victory with 44 percent of the popular vote—a law was passed quashing criminal investigations of members of the National Socialist government. It only took until August—less than half a year—to reorient the organs of the Bavarian bureaucracy to the National Socialist agenda. Pivotal to this process was Dachau. The former gunpowder factory in this artists’ town just north of Munich was converted 15 days after the election into a concentration camp for Bavaria’s thousands of political prisoners. The camp served as a container for persons in “protective custody”—and as a threat to the rest. By May, its intended effect had been achieved. “Dear Lord, O make me dumb,” went a bedside prayer of the time, “Lest to Dachau camp I come!”

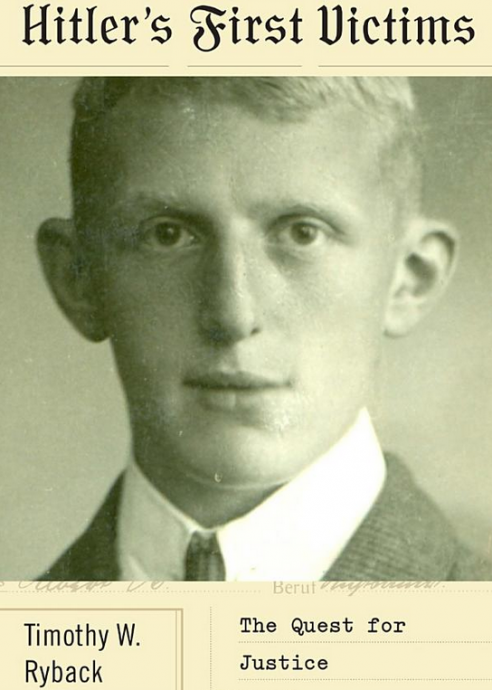

In Hitler’s First Victims: The Quest for Justice, historian Timothy W. Ryback presents a meticulously researched but also highly readable “micro-history” of the Dachau camp. A kind of forensic reconstruction based largely on archival sources, it retraces the Bavarian predilection for political violence from 1919 to 1933, the lives and the violent deaths of the camp’s first victims, and—perhaps most significant for our understanding of personal liberty—the dogged attempt by Josef Hartinger, a mid-level prosecutor within the Bavarian Ministry of Justice, to prosecute a homicide case against the camp’s SS overseers.

This micro-history reanimates Dachau and Munich, Bavaria’s capital, in those first few months as the movement penetrated the machinery of the state. What went wrong and why? What measures, and what kind of human beings, would it have taken to stem it? As will be seen, the evidence that Ryback provides suggests different conclusions than he himself arrives at. But his achievement is still considerable.

The book weaves four strands into a single narrative: the succumbing Bavarian state; the divided yet increasingly malleable Bavarian society; the first criminal acts at Dachau; and the bureaucratic-legal hero who sought to establish their criminality.

First, the state. The narrative recounts the suspension of civil liberties and “unprecedented wave of arrests” that followed the February, 1933 Reichstag fire and the fateful election held soon after. Thousands were taken into protective custody, usually without formal charges. Then Heinrich Himmler, as the new police chief, announced the opening of the Dachau concentration camp for political prisoners.

A makeshift facility, the camp bore no resemblance to other Bavarian penal institutions. SS political guards, who quickly replaced the Bavarian state police, took regular, brutal revenge on selected members—usually Jewish—of the camp’s mixed collection of Social Democrats, communists, professors, lawyers, and ordinary criminals. Before long, the camp officially became its own jurisdiction—hence beyond the reach of the Bavarian criminal code.

Ryback recounts the central government’s swift takeover of the Free State of Bavaria, which had been governed by the Bavarian People’s Party for a decade. It was enabled by Article 2 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the Reich government to “temporarily assume the responsibilities from the state authorities as necessary” to reestablish public safety and order. The central National Socialist-led government orchestrated a public disturbance, then invoked Article 2, allowing it to dismiss the Bavarian cabinet and replace it with Reich governor Epp and a clutch of National Socialist ministers.

Within a few brief months, the central government—and with it, the Nazi Party— overwhelmed the Bavarian bureaucracy and judiciary, which was at the time the sole institution with legal jurisdiction to prosecute the criminal acts that occurred at Dachau. By mid-May, one local official would lament, the “state’s authority is threatened by unwarranted attacks from all sides from political functionaries in the normal administrative machinery.” By the end of the summer, the process was complete.

It is tempting to speculate that Article 2 made all the difference; that without it, Bavaria and the other member states could have avoided a National Socialist repurposing of their bureaucracies and judiciaries, ultimately, into instruments of political murder. The thesis is attractive. Yet it may well be facile. Ryback reminds readers that German judiciaries had already been politicized a decade prior.

He presents a 1922 study by Ernst Gumbel, a statistics professor who had tracked judicial proceedings for political murders committed from 1919 to 1922 throughout Germany. Gumbel found that 330, “of which four were perpetrated by the left and 326 by the right, were never prosecuted and remained unprosecuted today.” The worst sentencing rates were in Bavaria. In Munich I and II in particular, presiding judges had had shown particular leniency to those accused of unlawful executions of Left-wing prisoners. Gumbel’s point: political murder, to become widespread, needs the judiciary to turn a blind eye. Ryback’s point: before the Gleichschaltung of the member states in 1933, the various state judiciaries and Bavaria’s in particular had already done this on a smaller scale.

Which returns us to Bavaria in 1933. Ryback depicts a society “swept up” in a renewed round of violent political adventure—with a mixture of enthusiasm of a large minority combined with a growing fear of the camp among the rest. As the spring unfolded, Bavarians adjusted to the new normal: recourse to protective custody to punish even ordinary acts (one fellow was arrested for saying “Hitler can kiss my ass” in casual conversation) and a rapid increase in violence. Ryback cites a New York Times report observing a “serious, hushed manner” in Munich’s streets—even in the normally raucous Hofbräuhaus. A pained, terse, death announcement among the photos reproduced in the book evinces the same quality: a Jewish city councilor from Bamberg and his wife announcing simply that their son had been “suddenly torn from us by death” and that his funeral had occurred in silence.

That son was 25-year-old Wilhelm Aron, a junior attorney and one of the first beaten and murdered at the Dachau camp. Ryback recounts Aron’s death—along with the others, all Jews—in grueling detail. One might wish for less detail except that it conveys, in very effective manner, how Dachau was rife with both targeted, politically-driven revenge and garden variety sadism. It is not surprising that, in this brutal and arbitrary atmosphere, some detainees committed suicide after only a few days in the camp. And the forensic photos included in the book are a graphic reminder that these were crime scenes—though at this stage, still of individual crimes and not yet of mass murder.

But who took the forensic photos—and who retained them? This strand of the narrative marks the original contribution of Hitler’s First Victims, namely its record of the repeated return to the camp of two mid-level Bavarian bureaucrats from the Munich II zone to examine the corpses and to document the causes of these individuals’ deaths. The book reconstructs the efforts of Munich II prosecutor Joseph Hartinger, assisted by Munich II medical examiner Moritz Flamm, to prosecute the early Dachau killings as homicides under Bavaria’s criminal code. Hartinger’s goal was to obtain a conviction for a chain-of-command order for the multiple murders that had occurred in the first weeks of the camp’s operation.

In Hartinger, we find a kind of anti-type to the National Socialist bureaucrat of Hannah Arendt’s 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ryback portrays a human being who was ordinary—but by no means banal. This career civil servant lived comfortably. A Bavarian Catholic, he had a wife, a five-year-old, and good career prospects. In contrast to Adolf Eichmann, Hartinger was a gifted and competent lawyer. He had also demonstrated courage in the First World War, and pugnacity in his legal prosecutions. Despite the danger to his person and the hesitation of his superiors, Hartinger showed both fastidious professionalism and moral courage in building his case against the murderers at Dachau.

His colleague Moritz Flamm was, by this account, of a similar type. Hartinger’s immediate superior, Munich II senior prosecutor Karl Wintersberger, does not come off as well. He ultimately signed the murder indictments Hartinger had prepared; but in the “politic” manner of too many senior bureaucrats, Wintersberger, presumably as a courtesy, informed Himmler (who was now, besides police chief, special adviser to Minster of the Interior Adolf Wagner) that the indictments would be coming. The indictment papers were intercepted before they could be delivered. They sat untouched in Wagner’s office until 1945, when they were found by a United States intelligence officer. The papers became instrumental in building the case against senior SS members in the Nuremburg Trials.

This is a well-written and well-researched book, a vivid contribution to our understanding of all that went wrong in Germany those few months in 1933. Above all, its portrayal of Hartinger’s actions in those circumstances compels us to reflect on the moral and professional virtues that characterize excellence in a public official. And yet one must still take issue with its central point. Ryback writes that his intention is to “demonstrate that if Germany had found more individuals like Hartinger, perhaps history could have been set on a different, less horrific path.” His point that the German Sonderweg was not inexorable is a well taken. On the other hand, his own narrative suggests that it would have taken hundreds of thousands of courageous individuals, and further, that by 1933, those individuals would have had to engage in active civil war rather than documentation of Nazi crimes as they unfolded. Hartinger’s courage is clear enough, as is the ultimate usefulness of the documents he prepared. Yet the futility of his own attempt to prosecute the Dachau perpetrators demonstrates that a thousand individual acts like his would not have sufficed at that point. The Bavarian state was being repurposed. By March 1933, things had come to a desperate pass.

“I was only doing what my sense of duty and my professional oath demanded.” Thus spoke Hartinger when he later dismissed efforts to honor him for his work in 1933. The good bureaucrat. But in 1933, the dutiful upholder of the Weimar Constitution was already being replaced by another type. Under the National Socialist regime, as Arendt ably demonstrated in her Eichmann book, the defender of constitutional democracy had to resort to means not simply outside of but against the totalitarian state. And it is clear from this portrayal that Hartinger, who later also served in the Second World War on the German side, was unwilling to go there. One ought not dismiss the significance of his efforts against the Dachau murders—but one shouldn’t overstate it, either.