The Basic Decency of Republican Self-Government

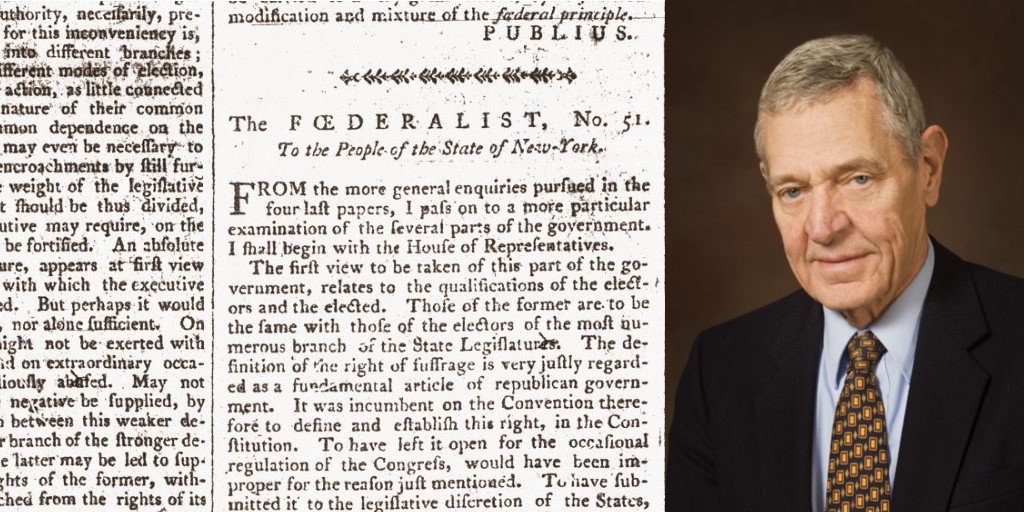

Five years after his passing, George W. Carey’s project—the recovery of constitutional republicanism against decades of revisionism—has assumed new urgency. Carey never fawned over the likes of Madison, but neither could he abide facile denunciations of them. Thus the title he gave to Liberty Fund’s invaluable collection of some of his best essays: In Defense of the Constitution.

For a student of Carey, to read these essays anew is to appreciate once more one’s illimitable intellectual debt to an unassuming man of deeply rooted convictions whom I once heard, and rightly, described as “the last of the gentleman scholars.” He was a conservative of the old school who likened reading Burke to listening to Mozart.

There was not an ounce of self-promotion about the man. I once discovered one of his masterworks, The Federalist: Design for a Constitutional Republic, tucked away on a bookstore shelf years after I had started studying with him. He had never, in the manner for which many a scholar is notorious, referred me to it despite its definitive explication of the definitive text of American thought. His students are likelier to recall the hours spent conversing with him in a broken chair in his inconspicuous office, sitting in a broken chair he never wanted to bother anyone with fixing. A silence of any length from a student would provoke an email whose subject line inquired as to his or her “existential status.”

Carey’s kind and quiet nature did not reveal what this book does: He was one of the foremost scholars of American political thought of his time or any. The essays collected here, each introduced by Carey, are essentially concerned with misperceptions of the American Founding, primarily those perpetrated by the Progressive movement, especially as they pertain to republican self-government.

Thus their abiding concern with the transfer of authority from a deliberate people to an untouchable Supreme Court that he likens in his essay “Abortion and the American Political Crisis” to “the pure democracy that Madison detested, all the more so as ideology grips a majority of its members, because impulse and opportunity for action so readily coincide.” The revisionist association of democracy with immediacy sought to convert the American regime from what Oakeshott called “nomocratic”—concerned with rules, with the range of decisions open to a deliberate people—to a “telocratic” one of ends, however they might be most readily achieved. Thus Carey:

What seems increasingly clear in recent decades is that the revisionists, off at the end, have given primacy to ends over means; that is, their commitment to majority rule is secondary to their commitment to democratic ends which, to a great extent, come down to egalitarianism mixed with virtually unbridled liberty.

The result is a “new constitutional morality … that is inimical to the older morality wrought by the Framers and articulated in The Federalist.” Carey calls this morality “revolutionary” because of its “repudiation of the basic principles upon which our constitutional system was founded.” The power of the Court, he writes, is “perhaps the most visible example that can be offered to illustrated the altered character of our regime,” but it is not the only one. The abandonment of, indeed assault on, separation of powers is another.

And so he proceeds, step by step, to expose the fundamental errors of this repudiation. His essay “Publius—A Split Personality?” argues that The Federalist forms a coherent whole whose authors accommodated themselves to one another, as against Alpheus T. Mason’s canonical article undermining the authority of Publius by saying he spoke in many voices. Citing The Federalist with the familiarity of a theologian with scripture, Carey meticulously unravels the split-personality thesis by showing that Madison’s and Hamilton’s contributions were almost entirely compatible with each other, and that where they were not the tensions reflected difficult and “perhaps insoluble” tensions of republicanism.

On this account, The Federalist demanded its own reckoning separate from the private intentions or other writings of its authors. Carey for this reason always referred to “Publius” rather than to Madison or Hamilton. He concludes:

[P]ublius’s component parts knew full well the dimensions of the task before them, that perhaps the opportunity for a stronger union might never again present itself, and that, in addition, a united and coherent defense of the proposed Constitution would require them to trim their theoretical sails, that is, to accommodate themselves and their thinking to the implicit values and assumptions of the document, as well as to the sensibilities of each other.

His essay “Majority Rule and the Extended Republic Theory of James Madison” stands as the definitive exegesis of Federalist 10 and as a model of principled scholarship that seeks neither secret meaning nor a single stunning breakthrough but rather straightforward and holistic understanding of a text.

Carey’s method includes finding the “unarticulated assumptions” underlying the essay—not, again, an esoteric reading but rather an attempt to get underneath what Publius says. Carey thus demolishes Robert Dahl’s claim that Madison’s definition of faction is incoherent because no one ever confesses to opposing the public good by observing that Madison, unlike his modern critics, assumes an objective morality. As Carey explains by way of introducing the essay, “those who do not believe in an objective moral order cannot ‘enter’ Madison’s system; they must summarily reject it or, as I have intimated, question his motives or sincerity.” Carey understood the animating role interest played in Publius’ system, but rejected the idea of a Federalist devoid of concerns of virtue.

Carey rejects the pluralist reading of Federalist 10, instead showing “the emphasis that the Madisonian theory places on the cultivation and existence of a predominant independent force in our highest decision-making councils.” In other words, the balance of decision-makers on any given issue will not have an immediate interest in it, such that “on any given issue normally only a small proportion of the entire population is likely to be aroused or involved” This independent force, however, has been consumed by positive government, the avaricious appetites of factions and, importantly, the willingness of the government to borrow to sate them.

Carey shows, against the Progressive reading that Federalist 10 is anti-democratic, that it actually reflects a commitment to deliberate republicanism. Nowhere in the essay, he observes, does Madison raise a constitutional barrier to majorities, relying instead solely on the empirical conditions that naturally occur in an extended republic. There is particularly no reference to the Supreme Court as a barrier against abusive majorities. Instead, by the end of the essay Madison pronounces the disease of factions cured without any resort to constitutional mechanisms: The theory should hold in any extensive republic regardless of its particular constitutional forms.

“Separation of Powers and the Madisonian Model: A Reply to the Critics” similarly seeks to exculpate Madison from accusations of anti-democratic heresy. The misconstructions he dismantles continue to haunt American thought in the form of an assumption that the separation of powers is designed to inhibit majorities, with political fault lines merely forming around the question of whether that is a salutary feature of the system.

Instead, and this is Carey’s central and, I think, irrefutable premise, Madison explicitly distinguishes between two problems: the abuse of minorities by majorities, which he calls the problem of “faction” and solves wholly within the confines of Federalist 10, and “tyranny,” the exposure of the people to the arbitrary rule of the government, which he defines in Federalist 47 and solves in Federalist 51 through the separation of powers. He writes:

We may say, then, that the chief end sought through separation of powers was avoidance of capricious and arbitrary government. The end, however, can be stated more precisely and positively. Article XXX of the Massachusetts Convention of 1780, in which we find the injunction that no branch shall exercise the functions of another, concludes “to the end it may be a government of laws and not of men.”

The import of the distinction between majority oppression and governmental tyranny is not merely theoretical. Without it, the separation of powers, perhaps the cornerstone of Madisonian republicanism, is rendered duplicative and therefore undemocratic. For, as James MacGregor Burns, asked, why impose the seemingly gratuitous barrier of separation of powers if Madison has already solved the problem of faction without it?

Crucially, Carey shows that the separation of powers does not entail a free-for-all in which all constitutional actors seek to expand their territory as widely as possible. Enter constitutional morality, which must be broadly shared for the system to operate:

[M]adison must have presumed limits to the behavior he anticipated. His discussion, couched as it is in terms of conflict and competition, might well lead one to believe that such would be the normal state of affairs between the branches. But clearly, if this were the case, adoption of the model would be an open invitation to stalemate and catastrophe. For this reason, we can safely surmise that one unarticulated premise of the Madisonian system must have been that the members of the branches would hold substantially the same views regarding the legitimate domain of the three branches and that, moreover, these members would show a high degree of forbearance, high enough at any rate not to repeatedly push the system to the brink of collapse.

In “James Madison and the Principle of Federalism,” Carey pushes back on “the traditionalists,” who read Madison to endorse states’ rights. In this essay particularly but not exclusively, Carey does not flinch from flaws or inconsistencies in Madison’s thinking. There is not, one concludes from reading Carey, a coherent account of federalism at the Founding. Perhaps, Carey writes, there could not have been:

But, more importantly, it eventually leads us to inquire about the status of the federal principle itself. Could it be, in other words, that federalism, rather than being the product of a principled evolution from constitutional moorings, is really anchored only in political expediency wherein the relationship between the national and state governments at any given moment depends upon the mere will of the dominant political force?

Carey later wrote of a distinction between constitutional and political federalism, with the former, exemplified by Federalist 39, placing the state and national governments in fixed spheres superintended by the Supreme Court, and the latter, reflected in Federalist 44 and 46, allowing the “common constituents” of the state and national governments to decide through their representatives in Congress where they wanted to allocate authority.

Tending to defend political federalism, Carey notes that Madison limits its scope by containing the federal government to its enumerated powers. Noting that Madison never supplies the “rules of the Constitution” according to which Federalist 39 says disputes over federalism will be settled, Carey returns to his recurrent theme of republicanism: Political federalism “would oblige those who might contend that the national government has overstepped its bounds to make their case in the political arena in hopes of persuading Congress to reverse itself.”

Madison’s views on federalism cannot be made consistent, Carey concludes. But perhaps there is a silver lining in Madison’s failure to specify clear rules on the topic:

In the last analysis, the search for such rules and principles would appear to be futile. But this very futility is, in our judgment, the profoundest lesson to be derived from Madison’s teachings on federalism; namely, we are forced to rely upon our own best resources for resolving jurisdictional disputes.

Those republican resources are the ones on which he would have us draw rather than reflexively resorting to the Court to resolve social disputes, the preoccupation with the concluding brace essays in this book, which concern, respectively, judicial review, due process and the fifth amendment, and, finally, the Court’s hijacking of the issue of abortion.

Carey was inveterately suspicious of what Mary Ann Glendon calls “rights talk,” especially when used to undermine republicanism by transferring issues to the Court: “Without rights, this is to say, the Court is without the wherewithal to usurp the legislative power or to transform itself into the most powerful branch. So much, I believe, can be seen by asking what the status of the Court today would be without a bill of rights.” This kind of “natural rights dogma” can be sustained only by excerpting the individual from a social context and making him “a moral universe unto himself,” an ethic fundamentally hostile to constitutional self-government, in which the people govern themselves with regard for “transcendent or higher moral law….”

The difference is important to Carey’s thought: His skepticism of “natural rights dogma” was not moral skepticism; far from it. It arose rather from a moral concern about the isolating and anti-political effects of rights talk. By contrast, his devotion to fundamental law as the basis of constitutionalism enables the dignity of self-government.

A critic of substantive due process, Carey carefully traces the history of that clause in the Fifth Amendment to show it cannot bear the weight placed on it. Here his republicanism is again manifest:

In defending substantive due process, as I have remarked, it is fashionable to speak of legislatures passing unreasonable, evil, and oppressive laws, laws that are offensive to our sense of justice or decency. Now this argument—at least in the abstract—presupposes that there is a fundamental agreement on a wide range of values so that, for example, the conditions that constitute injustice can be readily discerned. Indeed, I would argue that it is precisely this presumption that renders the argument so appealing to many. But if there is such a consensus over right and wrong, just and unjust, why would the representatives act contrary to these consensual norms?

Carey thus endorses the basic decency of republican self-government. It is ironic, then, that libertarian constitutional theorists today could so easily substitute for the Progressive critics of the Constitution whom Carey debunks: obsessed with the individual rights, placing primacy on the Declaration and exalting the Court. It is a mark of the enduring character of Carey’s thought that his constitutionalism, like the founding he did so much to explain to generations of students and readers, so transcends momentary disputes in favor of the permanent questions of political life.