America has enormous power, but the Biden Administration and the Federal Reserve are abusing it.

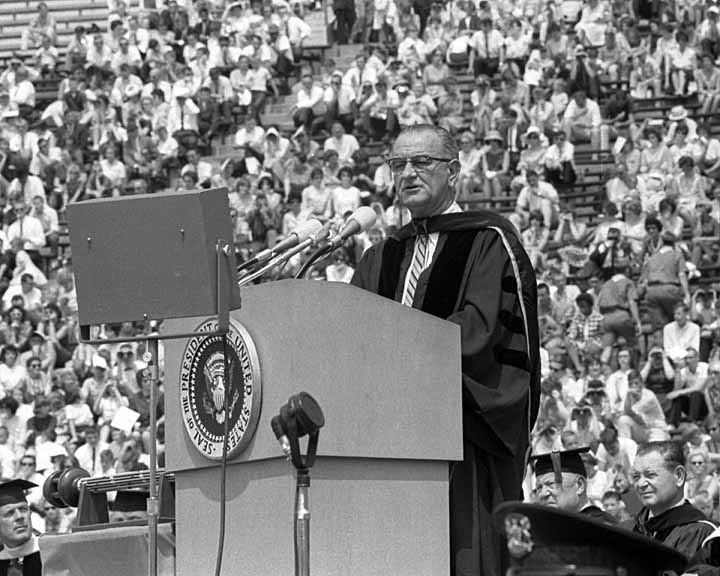

The Great Society, a Half-Century On

President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” speech is about to turn 50 years old. The speech, which the President gave as the commencement address at the University of Michigan on May 22, 1964, is a milestone in American history and instantly lodged that phrase in our political vocabulary.

The most grandiose political slogan in a roster that includes the New Deal and the New Frontier, the Great Society was more than a set of policy objectives. Rather, Johnson described it as the commitment to undertake an eternal quest, one that would elevate American civilization by expanding the federal government’s responsibilities and capabilities. The Great Society, he said, is “not a safe harbor, a resting place, a final objective, a finished work. It is a challenge constantly renewed.”

Rather than vindicate an ambitious conception of what government could and should do, however, the Great Society’s leading political accomplishment was to raise doubts about activist government’s competence and legitimacy, doubts which have beset liberalism ever since.

As a governing concept, the Great Society encompassed so many gauzy aspirations that it was never easy to say what it was about or be sure what it was not about. “The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all” and “demands an end to poverty and racial injustice,” Johnson said in Ann Arbor. “But that is just the beginning.” With the help—if that’s the right word—of speechwriter Richard Goodwin, Johnson laid out goals for Americans to pursue with the guidance of experts retained by the federal government.

The Great Society, the President said, is a place:

“where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents”; “where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness”; “where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community”; “where man can renew contact with nature”; “which honors creation for its own sake and for what it adds to the understanding of the race”; “where men are more concerned with the quality of their goals than the quantity of their goods”; and, “most of all,” it is “a destiny where the meaning of our lives matches the marvelous products of our labor.”

In Johnson’s Great Society, the concern and intercession of social scientists, helping professionals, and government officials would be elicited by every kind of unhappiness— except, that is, for unhappiness about the attentions of social scientists, helping professionals, and government officials.

The limitless agenda Johnson outlined rested on ideas already well established in liberal circles. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., for example, in one of his essays of the 1950s, declared:

Today we dwell in the economy of abundance—and our spiritual malaise seems greater than ever before. As a nation, the richer we grow, the more tense, insecure, and unhappy we seem to become.

The postwar economic boom, and the expectation that it would endure and expand forever, heralded the transition from the New Deal’s “quantitative liberalism” to a “qualitative liberalism” that would, wrote Schlesinger, be “dedicated to bettering the quality of people’s lives and opportunities.” It would “oppose the drift into the homogenized society” and “fight spiritual unemployment” in much the same way that quantitative liberalism “once fought economic unemployment.” Liberals must wage this fight by addressing “the quality of popular culture and the character of lives to be lived in our abundant society.” Schlesinger, moreover, saw the “greatest threat to American liberty” coming “less from the people who do not want others to be free than from the people who do not want to be free themselves.”

Neither he nor President Johnson endorsed the Rousseauian solution of forcing people to be free. Instead, both envisioned a therapeutic enterprise that would help (and help, and help) them to be free, given that the “greatest need in America” was “the revival of individual spontaneity.” (The Schlesinger quotations are from The Reporter, May 17, 1956, and Saturday Review, June 8, 1957.)

This qualitative liberalism promoted by the Great Society rested on four fallacies, two of them theoretical. First, the “problems” the Great Society was meant to address—such as “loneliness and boredom and indifference,” to quote Johnson’s speech—are better understood as dissatisfactions inherent in the human condition than remediable social dislocations. Second, the idea that these “problems” legitimately fall to government to try to solve, is dubious and dangerous—especially for a government deriving its just powers from the consent of the governed, as opposed to a theocracy claiming legitimacy on the basis of revealed truths.

The third error, which manifested itself empirically after 1964, has to do with practical capacity. The Great Society presupposed that republican government possesses not only the moral authority but the ability to comprehend, and then solve, a problem like spiritual unemployment. Even two politically sympathetic scholars wrote in The Liberal Hour: Washington and the Politics of Change in the 1960s (2008) that “the central and ultimately fatal germ of 1960s liberalism” was the conviction that “every problem has a solution and that the government in Washington is most likely to provide that solution.”

Fourth, it turns out that Schlesinger, Johnson, and the other promoters of qualitative liberalism badly misread the historical circumstances of mid-20th century America. The Great Society was presented as the construction of a splendid structure upon the foundation laid by the “brilliant success,” as Schlesinger styled it, of quantitative liberalism in providing prosperity and security. Liberals “should be able to count that fight won and move on to the more subtle and complicated problem of fighting for individual dignity, identity, and fulfillment in a mass society,” he wrote. Qualitative liberalism treats the triumphs of quantitative liberalism “as the basis for a new age of social progress, and seeks to move beyond them toward new goals of national development.” The foundation proved to be far from secure, however.

We should resist the temptation to ascribe LBJ’s spectacular political downfall to the Great Society’s fatuities. (In November 1964, he won 61.1 percent of the popular vote, which remains the largest percentage received by any presidential candidate since James Monroe in 1820. By 1968, he was too unpopular to seek his party’s nomination, or even attend its national convention.) We may, that is, safely assume that very few Americans voted for Johnson because they actually expected his administration would satisfy their desire for beauty and hunger for community, then abandoned him soon thereafter because the meaning of their lives did not match the marvelous products of their labor.

The real problem was not that government under Johnson failed at tasks no government had previously completed or even attempted. It was, instead, the failure at undertakings long understood to be incumbent upon any government, such as—to cite the Constitution’s preamble—justice, domestic tranquility, the common defense, and the general welfare. The most egregious failure was Johnson’s policy in Vietnam, which produced neither peace, nor disengagement, nor victory, just an endless, increasingly bloody stalemate in a war the President would not or could not convincingly justify. LBJ acted, according to Michael Barone, “as if he were trying to sneak the nation into a war,” to “wage a war without really saying so to the American people.” Johnson’s attempt to find an Aristotelian mean between going and not going to war was not only geostrategically but politically disastrous.

The Great Society speech made just one brief mention of foreign affairs, calling on the Michigan graduates to “join in the battle to make it possible for all nations to live in enduring peace—as neighbors and not as mortal enemies.” The achievement of global harmony sounded like it was still far off. In contrast, Johnson characterized endless prosperity as if it were at hand. Indeed, he argued that the only real economic problem was not securing abundance, but the prospect that it would prove disappointing or even harmful. That is, having largely succeeding in creating “an order of plenty for all of our people” over the 50 years prior to 1964, Americans faced a “challenge” in “the next half-century”: whether “we have the wisdom to use that wealth to enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization.” Failing to meet that challenge would turn us into “a society where old values and new visions are buried under unbridled growth.” Unless we “prove that our material progress is only the foundation on which we will build a richer life of mind and spirit,” Johnson warned, America will be “condemned to a soulless wealth.”

And consider that the President spoke even more expansively about the economy in private than he did in public. “Hell, we’re the richest country in the world, the most powerful,” he told Goodwin in one conversation. “We can do it all, if we’re not too greedy.” He took the same tone in another: “Hell, we’ve barely begun to solve our problems. And we can do it all. We’ve got the wherewithal.”

Even before Johnson left office, the public had good reason to doubt that the wherewithal to “do it all” was really all there. The increasing inflation brought on by Johnson’s unwillingness to choose between guns for Vietnam and butter for the Great Society was the first ominous sign. Next came the Arab oil boycott of 1973. That really marked the end of the Johnsonian Affluent Society—the idea that smart Keynesians had solved the age-old problem of want by using newly discovered tools of macroeconomic management.

In the four subsequent decades, America has known periods of economic vigor, such as the mid-1980s and late-1990s, but has never regained anything like the postwar boom’s blithe assurance that happy days were here again, forever. Just think how relieved millions of Americans in our own time would be—those who have witnessed or experienced downsizings and foreclosures, who have seen or been adults in their thirties and forties moving back home with their parents—at the prospect of unbridled growth and soulless wealth.

Our current President’s misbegotten foray into extemporaneous sociology was an attempt to explain why so many embittered working-class Americans “cling to guns, or religion, or antipathy to people who aren’t like them, or anti-immigrant sentiment, or anti-trade sentiment.” Warming to his subject, he said:

Here’s how it is: in a lot of these communities in big industrial states like Ohio and Pennsylvania, people have been beaten down so long, and they feel so betrayed by government, and when they hear a pitch that is premised on not being cynical about government, then a part of them just doesn’t buy it. . . . But the truth is that our challenge is to get people persuaded that we can make progress when there’s not evidence of that in their daily lives. You go into some of these small towns in Pennsylvania, and like a lot of small towns in the Midwest, the jobs have been gone now for 25 years and nothing’s replaced them. And they fell through the Clinton administration, and the Bush administration, and each successive administration has said that somehow these communities are gonna regenerate and they have not.

Unless the final 32 months of Barack Obama’s presidency witness the most spectacular economic growth since the Industrial Revolution, his will be the next in the succession of administrations that failed to deliver on promises that industrial jobs and communities would regenerate rather than continue to decline.

Obama’s remarks, it will be noted, came at a 2008 campaign fundraising event, not a policy seminar. The candidate’s analysis did not concern the governing challenge of devising policies to actually extend economic security and opportunity to disaffected voters. Rather, he was addressing the electoral challenge of persuading them to suspend a justified sense of betrayal and cynicism, and entertain the possibility that activist government can help them.

That political concern preoccupied many other Democrats. In a post-mortem on John Kerry’s defeat in 2004, Noam Scheiber of The New Republic wrote, “Democrats have run up against the limits of what they—or anyone else—can do to create and protect good jobs, the top economic priority of working-class voters,” who “seem more and more aware” of this fact. And because these voters think neither political party will deliver good jobs, they incline to the more culturally accommodating party, which does not disdain their views on guns, religion, or immigration.

Unlike Kerry, however, Obama won the presidency. And unlike Johnson, he stood for and won reelection. His victories, less than landslides but by no means cliffhangers, argue that Democrats can win elections and expand activist government despite not solving the policy problem of improving working-class prospects. The residual political force of the New Deal’s quantitative liberalism had allowed Michael Dukakis to carry the state of West Virginia in the 1988 presidential election, by a margin of 52 to 47 percent, even though he won only nine other states. By 2012, Obama lost West Virginia by 62 to 36 percent (and all 55 of its counties, unprecedented in the state’s history), yet won the national election comfortably.

The Great Society offered a liberalism for flush times, but the recollection of its goals, proclaimed though never achieved, has frustrated the formulation of a liberalism for harder times. Left-populism, seeking to occupy a political space somewhere between Franklin Roosevelt and Huey Long, thinks reviving the quantitative liberalism of aggressive regulation and redistribution is the answer. Whether a new New Deal would bring back a new Affluent Society is highly doubtful, however, as is the ability of such an agenda to sway the electorate. The victories of Mayor Bill de Blasio in New York City and Senator Elizabeth Warren in Massachusetts have seen Blue jurisdictions get bluer, rather than Red or Purple ones turn Blue. (In 2012, Obama got 78 percent of the vote in the five boroughs, and 61 percent of the vote in Massachusetts, against an opponent who had been elected its Governor 10 years earlier.)

The 1964 presidential election saw the widest gap in history between the two major party nominees on the question of how much the federal government could do and should attempt. The decisive victory by the champion of activist government, however, had unintended consequences for both parties, and for the nation. The liberal consensus swept past LBJ after the 1964 election at warp speed: The case for a new kind of government activism had rested on the belief that because America was in such good shape, its big problems solved or about to be, government had the right and duty to address questions about the quality of life and civilization. Four short years later, as Johnson left office, a new moralism came to define the liberal outlook, holding that America was in such terrible shape, as a moral and practical matter, that now government activism was urgently necessary to rescue a nation on the verge of collapse.

By 1968, Arthur Schlesinger could give a speech that called Americans “the most frightening people on this planet . . . because the atrocities we commit trouble so little our official self-righteousness, our invincible conviction of our moral infallibility.” Governmentally directed social transformations were no longer enhancements that would make a Good Society Great, but emergency measures needed to redeem the nation, averting a demise both imminent and deserved. The republic’s foundations had been discovered to be so fragile that millennial transformations were our only hope for avoiding anarchy.

The transformations that liberals said were indispensable turned out to be optional, however, even as the routine responsibilities they said could not possibly be discharged turned out to be within government’s capabilities. Upon examining the race riots that broke out in the summers of 1965, ’66, and ’67, for example, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (known as the Kerner Commission) reported that without “a commitment to national action—compassionate, massive and sustained,” requiring “unprecedented levels of funding and performance” for programs that “produce quick and visible progress” in black inner-city neighborhoods, the riots would continue and intensify. The nation enacted none of the Kerner Commission’s agenda—even President Johnson, who had appointed the commission, ignored its report—but the riots somehow ended.

Liberals applied the Kerner Commission argument more generally to America’s urban intifada, “the big-city crime wave of the sixties and seventies” that was, according to the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik, the “crucial trauma in recent American life.” There really was a “liberal consensus” on public safety: one that amounted to abandoning, in the words of a legal scholar cited by Gopnik, “all serious effort at crime control.” That abandonment consisted of the liberal insistence that the only feasible, just solution for the problem of crime was to remove its “root causes” by—what else?—enacting the maximal liberal social welfare agenda.

In ignoring this advice, America turned to the punitive measures liberals insisted would be futile and indecent: more police, more prisons, longer sentences, fewer paroles. The nation’s murder rate was 4.6 per 100,000 in 1962. It was at least twice that high in 10 of the 21 years beginning in 1973, during which it was never less that 7.9 murders per 100,000, a rate 72 percent higher than in 1962. After the 20-year decline that began in the early 1990s, however, during which crime’s alleged root causes remained rooted, the rate stood at 4.7 per 100,000 in 2011, the lowest level since 1964.

The list of ills that 1970s liberals said an un-transformed, unredeemed America would have to learn to live with included not only riots and crime, but high inflation. The economic journalist Robert Samuelson has argued that stable prices “are like safe streets, clean drinking water and dependable electricity. Their importance is noticed only when they go missing.” When they went missing in the 1970s, it was “a deeply disturbing and disillusioning experience that eroded Americans’ confidence in their future and their leaders.”

On the eve of Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981, after a year in which the Consumer Price Index had increased by 13.5 percent, one of the most prominent liberal economists, Lester C. Thurow, took to the pages of the New York Times to warn the President-elect: “You can declare war on inflation. But you cannot win a war against inflation. And if you insist on trying, you will simply grind up both the economy and your administration in a futile effort.” Indeed, “you can only cure inflation if you are willing to restart the Great Depression.”

America’s foremost exponent of Keynesianism, Paul Samuelson, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics the second year of its existence, was certain in 1979 that another Depression would be the least of it. “Today’s inflation is chronic,” he warned, with roots “deep in the very nature of the welfare state.” Attempts to end it through disinflationary monetary policy would require

abolishing the humane society [and would] reimpose inequality and suffering not tolerated under democracy. A fascist political state would be required to impose such a regime and preserve it. Short of a military junta that imprisons trade union activists and terrorizes intellectuals, this solution to inflation is unrealistic—and, to most of us, undesirable.

Reagan ignored all such advice. Instead, he supported the credit squeeze pursued by Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker. Within two years, inflation was broken. The Consumer Price Index, which had increased by 117 percent in the 10 years before Reagan took office, increased by 128 percent in the 25 years after. It has never had an annual increase exceeding 5.4 percent since 1982, having never had one less than 5.8 percent from 1973 through 1982. Somehow, this economic achievement necessitated neither a Depression nor a police state.

Liberals paid a heavy political price for choosing their policy goals recklessly, and discharging their governmental responsibilities fecklessly. Following his departure from the Johnson administration, which he had served as Assistant Secretary of Labor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote: “The stability of a democracy depends very much on the people making a careful distinction between what government can do and what it cannot do.” Thus, “to seek that which cannot be provided, especially to do so with the passionate but misinformed conviction that it can be, is to create the conditions of frustration and ruin.”

America and liberalism both suffered because liberals misread and misused the mandate won in the 1964 election by the champion of activist government. Against all expectations, conservatives who had followed that year’s champion of limited government to a historic defeat wound up with opportunities to govern, and set the terms of the national debate, beyond anything they had known since the New Deal.

It turns out, though, that the law of unintended consequences neither rests nor plays favorites. Conservatives made good use of the opportunities liberals’ failures provided, restoring public safety, a sound currency, and—in concluding the Cold War successfully—national security. Their reward, it seems, has been to open new possibilities for activist government. As journalist Matt Bai has written, when citizens “take for granted the basic competence of government” it “makes all the difference when you ask them to expand it.”