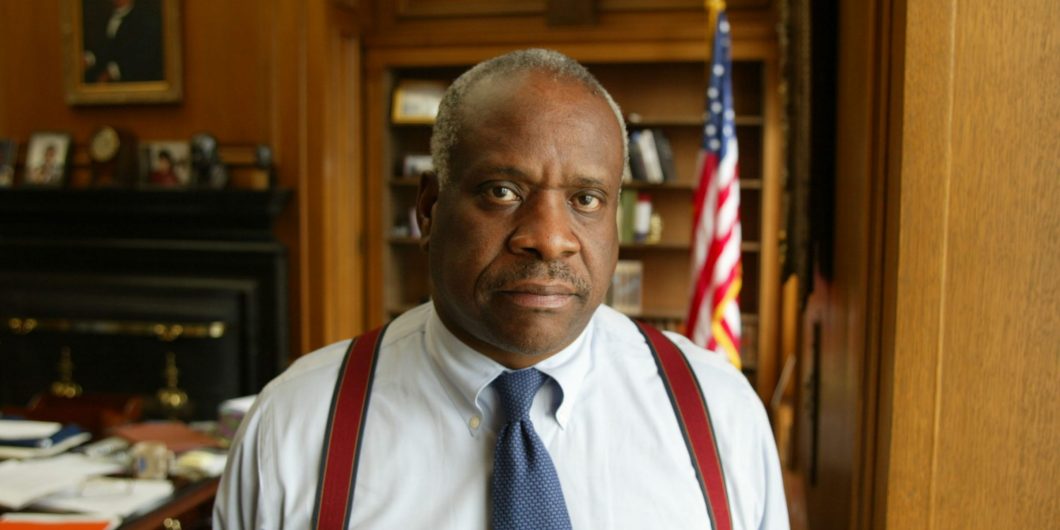

Justice Thomas: Mr. Republican

Once again Justice Clarence Thomas has given originalist jurisprudence its most robust defense through his revival of an obscure part of the U.S. Constitution.

In 2010, in McDonald v. Chicago, he had protected the right to individual gun ownership by invoking the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause. Now he has concurred in the decision in Evenwel v. Abbott (2016), which unanimously affirms the state of Texas’ use of population (rather than being required to use eligible voters) as the basis for devising electoral districts.

Thomas’ bold concurring opinion, reviving as it does Article IV’s guarantee that each state shall have a republican form of government, opens up a vast field of possibilities for thinking about apportionment but also about free government generally. His aim in directing us to this clause is ultimately to build a more powerful case against the unconstitutional administrative state, the suppressor of separation of powers, federalism, and basic republican principles. Even more provocative is the basis he sees for the Republican Government Guarantee Clause: the Declaration of Independence.

The thrust of this opinion is obviously contrary to conventional understandings, such as that of Jeffrey Toobin, for whom Thomas’ “separate opinion” showed “how extreme and out of touch his views are. In it, he challenged fifty years of consensus at the Court on voting rights by rejecting a bedrock principle: one person, one vote.”

On the contrary, Thomas did not reject “one person, one vote”—rather, he would not require it. “The Constitution does not prescribe any one basis for apportionment within States.” He pointed out that the states have “significant leeway in apportioning their own districts to equalize total population, to equalize eligible voters, or to promote any other principle consistent with a republican form of government.”

Thomas takes his bearings from the explicit constitutional standard of republicanism, not the vagaries of “equal protection,” an avenue of jurisprudence that leads to gibberish about “vote dilution” and other absurd mathematical understandings of politics.

Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution reads:

The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

So all three branches of the federal government must protect states from nonviolent as well as violent “regime change.”

Thomas’ opinion makes one fundamental point: The Court’s apportionment decisions have ignored the basic principle that “The Constitution lacks a single, comprehensive theory of representation. The Framers understood the tension between majority rule and protecting fundamental rights from majorities.”

This tension arose from the Declaration itself. Thomas writes: “Because, in the view of the Framers, ultimate political power derives from citizens who were ‘created equal,’ the Declaration of Independence, beliefs in equality of representation—and by extension, majority rule—influenced the constitutional structure.”

Indeed, he adds, many of the Founders “viewed antidemocratic checks as indispensable to republican government. And included among the antidemocratic checks were legislatures that deviated from perfect equality of representation.”

For example, one might add, Article V makes equal representation in the U.S. Senate of the unequally populous states of the union an unamendable principle. What prevents such practices from becoming contrary to republican government is their purpose. “The Framers believed,” writes Thomas, “that a proper government promoted the common good. They conceived this good as objective and not inherently coextensive with majoritarian preferences.”

In order for government “to promote the common good, it had to do more than simply obey the will of the majority.” It also had to “protect fundamental rights,” says Thomas, citing the Declaration of Independence, Blackstone’s Commentaries, and Federalist 43. (The sentence from Blackstone reads: “For the principal aim of society is to protect individuals in the enjoyment of those absolute rights, which are vested in them by the immutable laws of nature.”)

As for Federalist 43, we can read therein that American constitutionalism is based on recurrence to

the great principle of self-preservation; to the transcendent law of nature and on nature’s God, which declares that the safety and happiness of society are the objects at which all political institutions aim and to which all such institutions must be sacrificed.

In other words, to the Declaration.

A free society will always exhibit struggle. Therefore, as Thomas writes, “designing a government to fulfill the conflicting tasks of respecting the fundamental equality of persons while promoting the common good requires making incommensurable tradeoffs.”

In this enterprise the people are the ultimate sovereign, and the Court needs to show its respect for them. Thus, Thomas concludes, “In trying to impose its own theory of democracy, the Court is hopelessly adrift amid political theory and interest-group politics with no guiding legal principles.” The wisdom of the people should prevail over the theorizing of the academic and legal elites.

Justice Thomas’ reminder of the Republican Government Guarantee Clause comes at a propitious moment—when the very idea of republican institutions has come under fire from scholarly, legal, and political forces, and the administrative state appears to enjoy bipartisan approval. The boldness of this opinion becomes even clearer when we realize that it breaks a long silence on the clause. The Court’s last majority opinion mentioning it in any notable way was Luther v. Borden (1849).

The author of that opinion, Chief Justice Roger Taney, dismissed its application as a “political question.” Wrote Taney:

Under this article of the Constitution, it rests with Congress to decide what government is the established one in a State. For as the United States guarantee to each State a republican government, Congress must necessarily decide what government is established in the State before it can determine whether it is republican or not.

By making legal positivism—the will of Congress—the test for what is “republican,” Taney, I speculate, wished to denigrate the republican principles of the Declaration and then separate them from the Constitution.

An even sweeter victory for him would come about eight years later, following the Compromise of 1850, in Dred Scott (1857). There, the Chief Justice distorted the Declaration, as legitimizing slavery, to make it fit his conception of the Constitution. Together with John C. Calhoun, Taney laid the theoretical basis for the unlimited government of the administrative state by separating the Declaration, properly understood, from the Constitution and thus transforming willfulness into legitimacy.

I have argued before that the Thirteenth Amendment brought out the true meaning of the Republican Government Guarantee Clause, among other parts of the 1787 document, by restoring the original understanding of that document. The recognition of our natural rights defines legitimate government. Now we can see that a republican form of government means equality for all men. In America, slavery and republicanism are incompatible.

“None of the Reconstruction Amendments changed the original understanding of republican government,” writes Thomas. It’s a statement that reminds us of what one thinker called “the invisible slave” in constitutional interpretation. As an example, consider the Court’s reliance on dubious social science in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which was driven by the Court’s need to avoid the real issue of slavery and its badges and incidents.

This habit of obfuscation underscores the importance of the minority opinion from 1896 that referred to the Republican Government Guarantee Clause. Justice Harlan’s colorblind-Constitution dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson concluded:

Such a system [of racial segregation] is inconsistent with the guarantee given by the Constitution to each State of a republican form of government, and may be stricken down by Congressional action, or by the courts in the discharge of their solemn duty to maintain the supreme law of the land, anything in the constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

In writing to stop an unwarranted use of the Equal Protection Clause, Thomas is attempting to fulfill Harlan’s spirited defense of equal liberty.

In his various opinions—concurring, dissenting, and occasionally even for the Court—Clarence Thomas has cut through the accretions of scores of years of misinterpretations in all the major areas of constitutional interpretation, including religious liberty, free speech, separation of powers, and federalism. One could say his jurisprudence is “result-oriented”—that is, oriented toward protecting the ends that the Declaration of Independence demands through the Constitution, a republican government that protects safety and happiness.